Workers leave the Pullman Palace Car Works, 1893. From The Story of Pullman.

Every year in early September, a variety of reminiscences are published to explain Labor Day’s origins. The stories describe how the Pullman Strike of 1894 changed American labor laws and led President Grover Cleveland to create the holiday to appease workers after the strike ended. (This version of history has been debated.) Rarely do we hear the full story, one that would let us see how the strike and its leader, Eugene Victor Debs, subsequently helped galvanize the socialist movement in America. Many also fail to show how the strike should serve as a warning for union organizers for the next century.

Let’s start from the beginning, or from a beginning. George Pullman, the railway mogul and industrialist who owned the Pullman Car Company, founded the company town of Pullman for around twenty thousand of his workers and their families in the Southeast Side of Chicago in the 1880s. He charged his workers rent and imposed a behavioral code they needed to follow in order to remain in Pullman. For a time, the “model town” and its supposedly utopian vision of a working community won praise from the national media. (The neighborhood was made into a national monument in 2015 by President Barack Obama, highlighting its complex history.)

Pullman was designed to keep workers content enough to avoid unrest. The buildings were magnificent, everything was inordinately clean, homes had personal yard space in addition to expansive public parks, with maintenance and sanitation covered by the company. By building an appealing environment that seemed to focus on the health and contentment of its inhabitants, Pullman hoped to entice a skilled workforce to join him—and to avoid strikes. Though workers had access to libraries, churches, parks, shopping, and a man-made lake, there were also strongly enforced prohibitions against newspapers, town meetings led by workers, public speeches, and even taverns. Residents had to adhere to cleanliness standards, which largely existed only to give inspectors an excuse to invade their homes. A Pullman pastor explained: “It is a civilized relic of European serfdom.” It was a company town controlled by a paranoid baron who felt insecure about his power and did all he could to keep his employees placated enough to stay quiet—and it worked, until it didn’t.

The inherent inequality of this paternalistic structure was revealed during the economic depression of 1893, when manufacturing demand fell, pushing employers to cut wages by 25 to 30 percent while rent remained the same, making it increasingly difficult for workers to afford living even in a company town. As the story goes, a group of workers ventured to air their grievances with Pullman himself. He had them fired. Soon after, on May 11, 1894, many workers voted to strike and walked out.

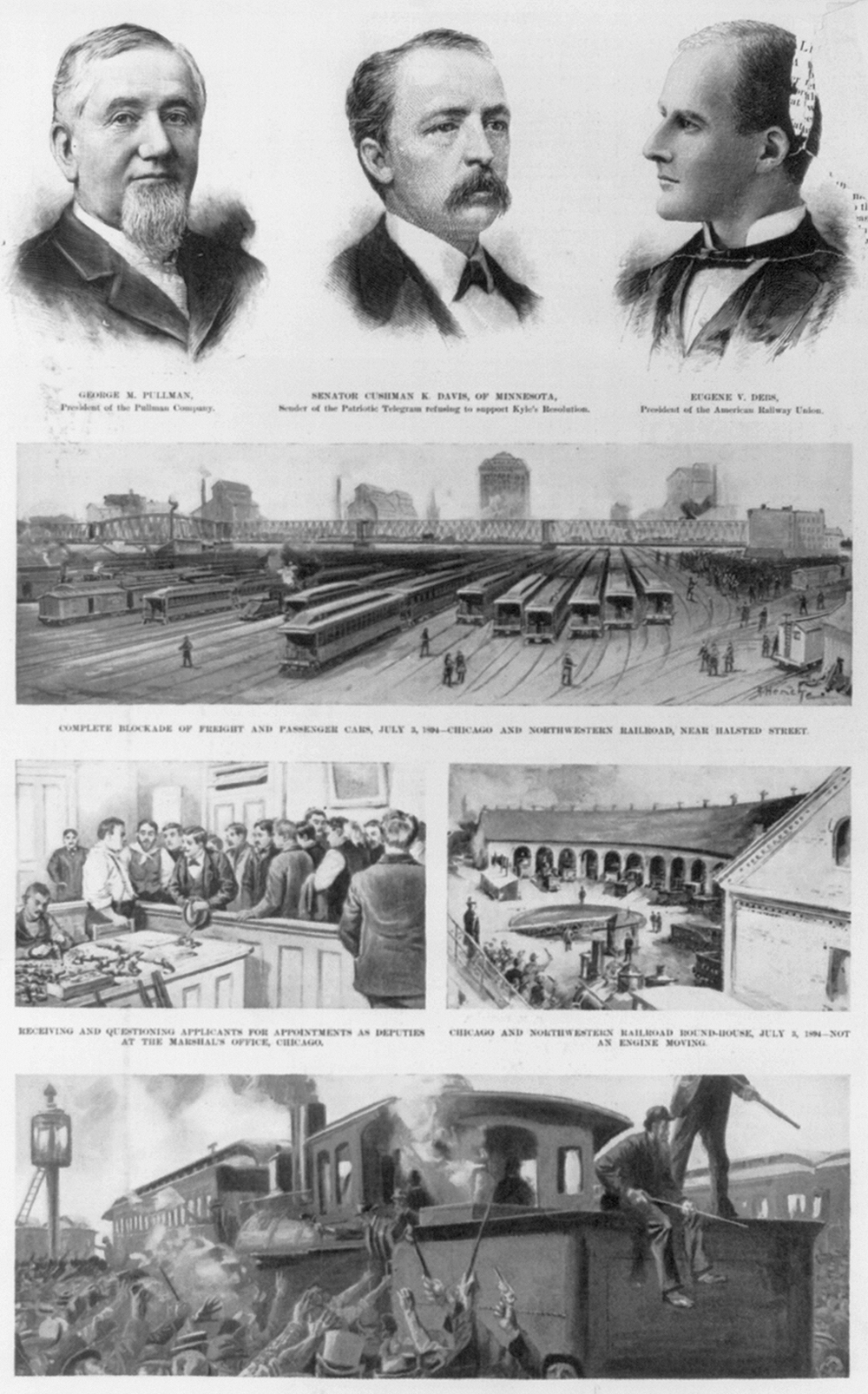

Meanwhile, Eugene Debs had recently experienced his first success with the American Railway Union (ARU), established in February 1893. Within a year, around 150,000 workers had joined the union, a membership pool that helped them win a strike against the Great Northern Railroad. When the GNR imposed severe wage cuts in 1893, the ARU helped initiate a strike action that lasted eighteen days and resulted in a group of arbitrators agreeing to roll back the cuts. This action would be the ARU’s only concrete victory.

There was no rest for the ARU despite a lack of resources. When the fed-up Pullman workers started their own wildcat strike (meaning it was instigated without a union’s authorization), they sent word to the ARU, hoping for its support. The Pullman strikers pleaded:

Pullman, both the man and the town, is an ulcer on the body politic, he owns the houses, the schoolhouses, and churches of God in the town he gave his once humble name.

And thus the merry war—the dance of skeletons bathed in human tears—goes on, and it will go on, brothers, forever, unless you, the American Railway Union, stop it; end it; crush it out.

Debs was skeptical at first, but after traveling to Pullman and speaking with the strikers, he changed his tune. He heard distressing stories from workers of being overworked and harassed by foremen. He saw how workers couldn’t provide for their families when wages dropped and rents remained static. Debs began to see how Pullman—a national company with a presence across America and tens of millions of users every year—could be an opportunity, though a less than ideal one, to build exactly the kind of national labor solidarity he envisioned for the ARU. He rallied the union, exclaiming that all “shall march together and fight together, until working men shall receive and enjoy all the fruits of their toil.”

The American Federation of Labor (AFL), headed by Samuel Gompers, opposed the ARU because it believed only skilled workers based in craft should be involved in unionization. Gompers believed that financial stability (which came from paying higher dues) was essential to maintaining the integrity of craft unions, and he insisted that other, non-craft workers could simply follow the AFL’s example, rather than accepting all workers into the AFL. The AFL denying assistance during the Pullman strike fractured the strike’s efforts from the beginning. The Pullman Company would not agree to enter arbitration to discuss wages, poor living conditions, or sixteen-hour workdays. In a stunning display of solidarity, more than 150,000 railroad workers across twenty-seven states then refused to service any trains with Pullman cars—nearly every train in use at the time. Suddenly, the American railway system was at a standstill. The Chicago Times wrote that while “some roads are absolutely and utterly blockaded, others only feel the embargo slightly, but it grows in strength with every hour.” The Nation suggested that “the present boycott is an attempt to starve out society.”

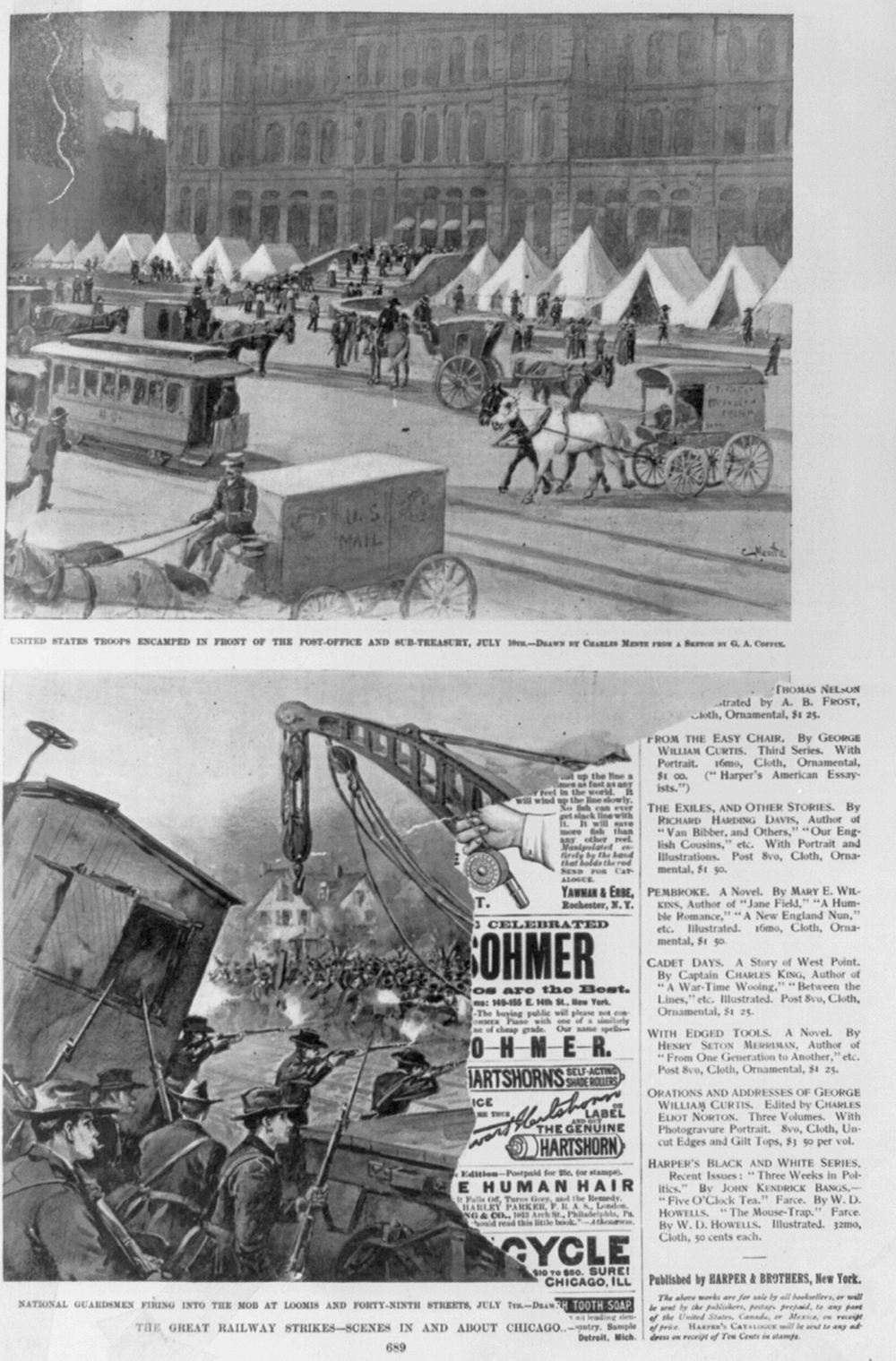

The effects of the strike were felt most intensely in Chicago itself, particularly as public transportation came to a halt after streetcar workers joined the strike. Violence broke out. As President Cleveland later wrote: “Almost in a night it grew to full proportions of malevolence and danger. Rioting and violence were its early accompaniments; and it spread so swiftly that within a few days it had reached nearly the entire Western and Southwestern sections of our country.” He wasn’t wrong. Freight cars were derailed, engineers were assaulted, tracks were blocked, and train cars and buildings were set on fire. Seventy-one strikers were jailed, and Debs was imprisoned for six months for his role in organizing the strike. He read Marx for the first time in prison.

Cleveland claimed the strike was illegal because the U.S. Postal Service relied on trains, which he believed meant that the strike was a federal issue. Around 14,000 soldiers and U.S. Marshals were sent in to break up the strike. More than thirty workers were killed and many other injured, mostly at the hands of national guardsmen, who at least once fired indiscriminately into a crowd, and class solidarity was not enough to maintain momentum. The strike failed. With Debs and others in jail, the ARU was forcibly dismantled, and Cleveland ordered a federal injunction to end the strike.

Debs challenged the legality of the federal injunction (which was initiated by Cleveland’s attorney general, Richard Olney—a former attorney for railroad companies), on the grounds that it was the railway employers themselves who had their laborers attach Pullman cars to mail trains in an effort to spur Cleveland into action. His challenge was denied by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled unanimously against him. One could argue that the boycott’s very success is what doomed it by bringing negative attention from the press nationwide and forcing a federal response. Labor historian and Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) member Toni Gilpin explained to me how the strike was ultimately imperiled by its faux comradeship: “It’s not clear that even had Sam Gompers weighed in on the side of the ARU that the strike could have been won. Clearly a fractured labor movement will be overcome by a united business class, especially one [that] has the military might of the federal government behind it.” Even the supposedly all-encompassing ARU failed to include black railway workers (a decision Debs supposedly opposed), which allowed Pullman to enlist black workers as strikebreakers. Railways were the largest industrial employer of African Americans at the time, and Pullman saw the benefit in being a leader in that area, able to hire a cheap workforce. Pullman did not allow blacks in his company town and actively discouraged them from joining workers’ unions. A labor movement without full unity among workers, Gilpin says, is doomed to fail.

Debs, born in Terre Haute, Indiana, in 1855, had joined his first union at the age of nineteen, the Vigo Lodge of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, as secretary. He came to believe that the only way to stand up to railway bosses was to create a real federation between all the brotherhoods and craft unions, which proved difficult under the current system. After resigning in frustration, he wrote:

Class enrollment fosters class prejudices and class selfishness, and instead of affiliating with each other, there is a tendency to hold aloof from each other...

It has been my life’s desire to unify railroad employees and to eliminate the aristocracy of labor, which unfortunately exists, and organize them so all will be on an equality.

During his six months in prison following the Pullman Strike, Debs studied socialism and talked to fellow prisoners who were socialists. He read the works of Karl Kautsky and Edward Bellamy as well as Marx. Bellamy is best known for his utopian novel Looking Backward: 2000–1887, a best seller in its time, which depicts the dangers of capitalism by envisioning a socialist future in the year 2000. Based on this education, though, Debs realized that no serious labor movement could succeed as long as the government remained ruled by the capitalist class. The only way forward that would have a lasting effect, rather than temporary reforms gained through strikes, would be to achieve political power for socialism. Two years after his release from prison, Debs wrote in the Railway Times, “The issue is Socialism versus Capitalism. I am for Socialism because I am for humanity. We have been cursed with the reign of gold long enough. Money constitutes no proper basis of civilization. The time has come to regenerate society—we are on the eve of a universal change.” Gilpin explained that Debs understood that the federal government’s intervention had changed the rules of the game, and “obviously not in the workers’ favor. Debs was propelled toward the expansion of solidarity across skill, race and gender lines and a new socialist political movement that could buttress workers’ industrial might.”

The figure of Eugene Debs shows the inextricable link between union organizing and socialist activism in America, with a congruent politics of collectivity and fairness based in community-based organizing. Disillusioned by the actions of both the Democrats and Republicans in supporting management, he formed the Social Democracy of America party, which would become the Socialist Party of America in 1901. He ran for president five times as the party’s candidate, including in 1920, while he was again imprisoned, serving three years (of a ten-year sentence) for antiwar agitation. He received nearly 920,000 votes, worth 3.5 percent of the popular vote. The decline from the 6 percent of the vote he earned in 1912 was partially due to the bifurcation of the socialist movement between the Socialist and Communist Parties. Meanwhile, Warren G. Harding ran a popular campaign focused on a “return to normalcy,” rejecting the idealism of Woodrow Wilson’s previous two terms in office and leaving little room for the ideas of a jailed socialist to catch fire.

As several labor historians have noted, the Pullman strike was rarely remembered in its full context, leaving workers’ voices largely unheard. Strike leader Thomas Heathcoate remarked during the boycott that “we do not know what the outcome will be, and in fact we do not care much. We do know that we are working for less wages than will maintain ourselves and families in the necessaries of life, and on that one proposition we absolutely refuse to work any longer.” Another worker told the Chicago Herald that “the only difference between slavery at Pullman and what it was down South before the war is that there the owners took care of their slaves when they were sick and here they don’t.” The impassioned Pullman workers boldly stated what they felt, and the simplified Labor Day story fails to do them justice.

The pioneering social worker and activist Jane Addams had attempted to facilitate arbitration at the beginning of the strike. She later wrote that before that boycott, “there had been nothing in my experience [that had] reveal[ed] that distinct cleavage of society which a general strike at least momentarily affords...During all those dark days of the Pullman strike, the growth of class bitterness was most obvious.” While Debs never achieved the revolution he hoped for, he did help build a movement out of that divide. In the same statement he made before his sentencing, he said, “This order of things cannot always endure. I have registered my protest against it. I recognize the feebleness of my effort, but, fortunately, I am not alone.”