“I Fall to Pieces” (Decca, 1961) and “Crazy” (Decca, 1961), by Patsy Cline.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from John Lingan, author of Homeplace: A Southern Town, a Country Legend, and the Last Days of a Mountaintop Honky-Tonk, out now from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

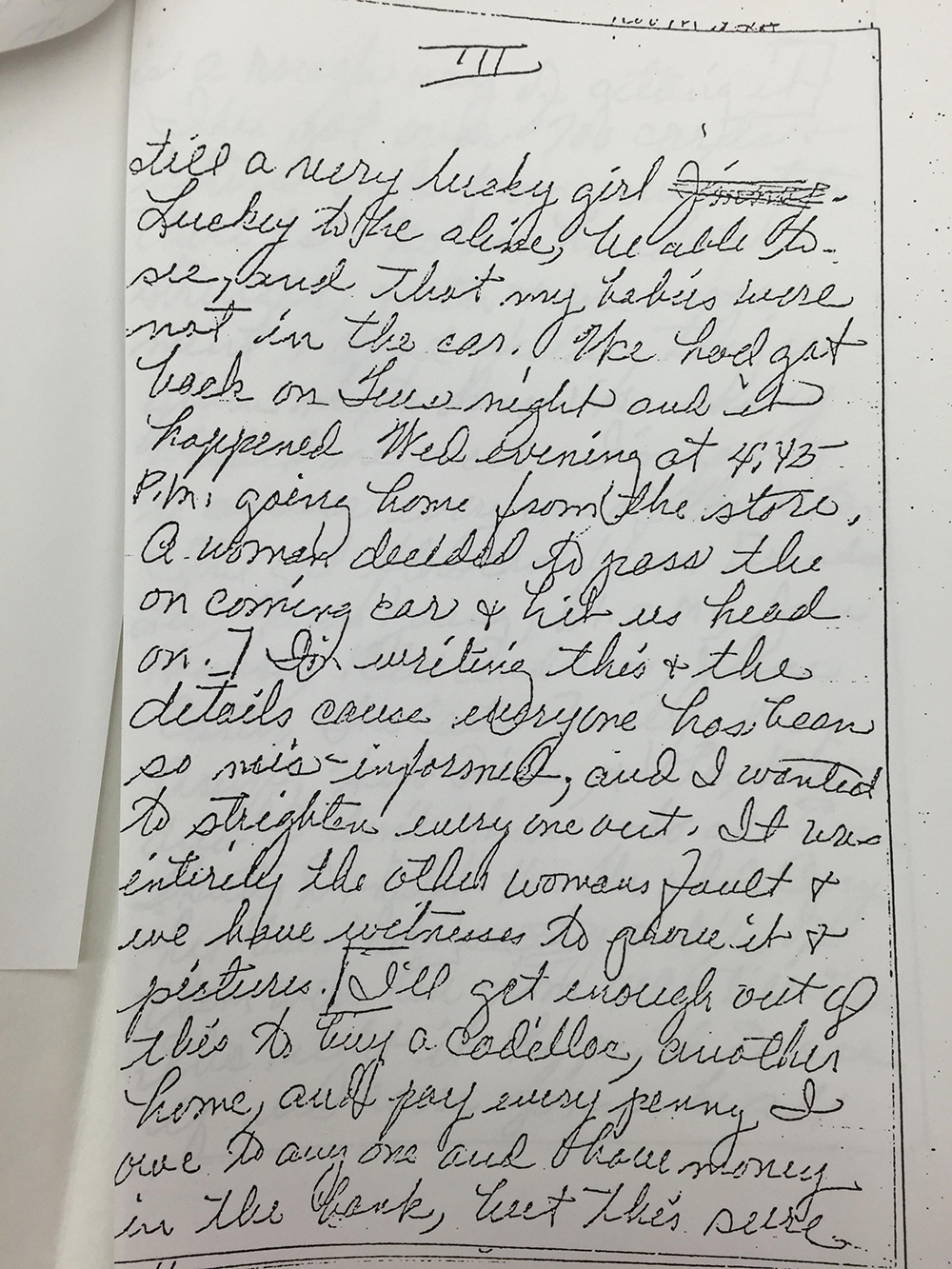

Patsy Cline’s death in March 1963 is a crucial episode in the long, sad history of musical careers ended by plane crashes. But fewer people know that she considered herself lucky to live even that long. In the summer of 1961, right after the release of her second, career-saving big single, “I Fall to Pieces,” Cline was hit head-on while running errands near her suburban Nashville home. In an eerie echo of her new song’s lyrics, she was brutally hurt, and spent a month convalescing at the hospital, eventually emerging to record her final run of legendary hits, primarily “Crazy,” which reached #2 on the charts in 1962.

My new book is all about her hometown, Winchester, Virginia, and the local friend who first put her on the radio, “Joltin’ ” Jim McCoy, who remained a revered DJ, songwriter, bandleader, and all-around country music impresario throughout Maryland and the Virginias for decades after Patsy’s death. Her legend is still a living thing in town; you can meet many people who knew her personally, or saw her sing, or got their soda fountain orders from her when she worked at Gaunt’s Drugstore in the 1950s. Her longtime home on Kent Street has become a historic property, made to look era-specific and filled with her belongings, including her renowned collections of gloves and salt and pepper shakers.

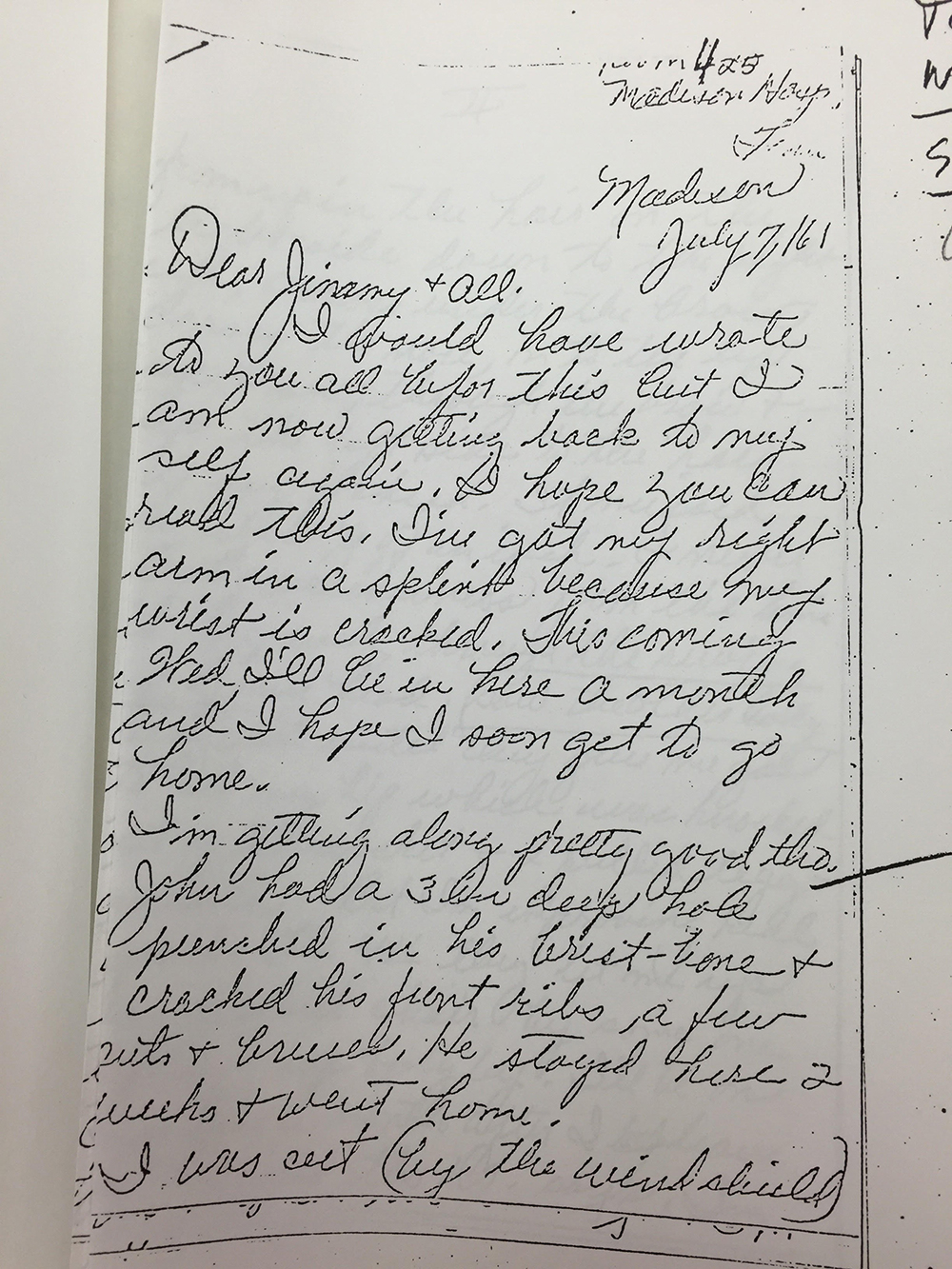

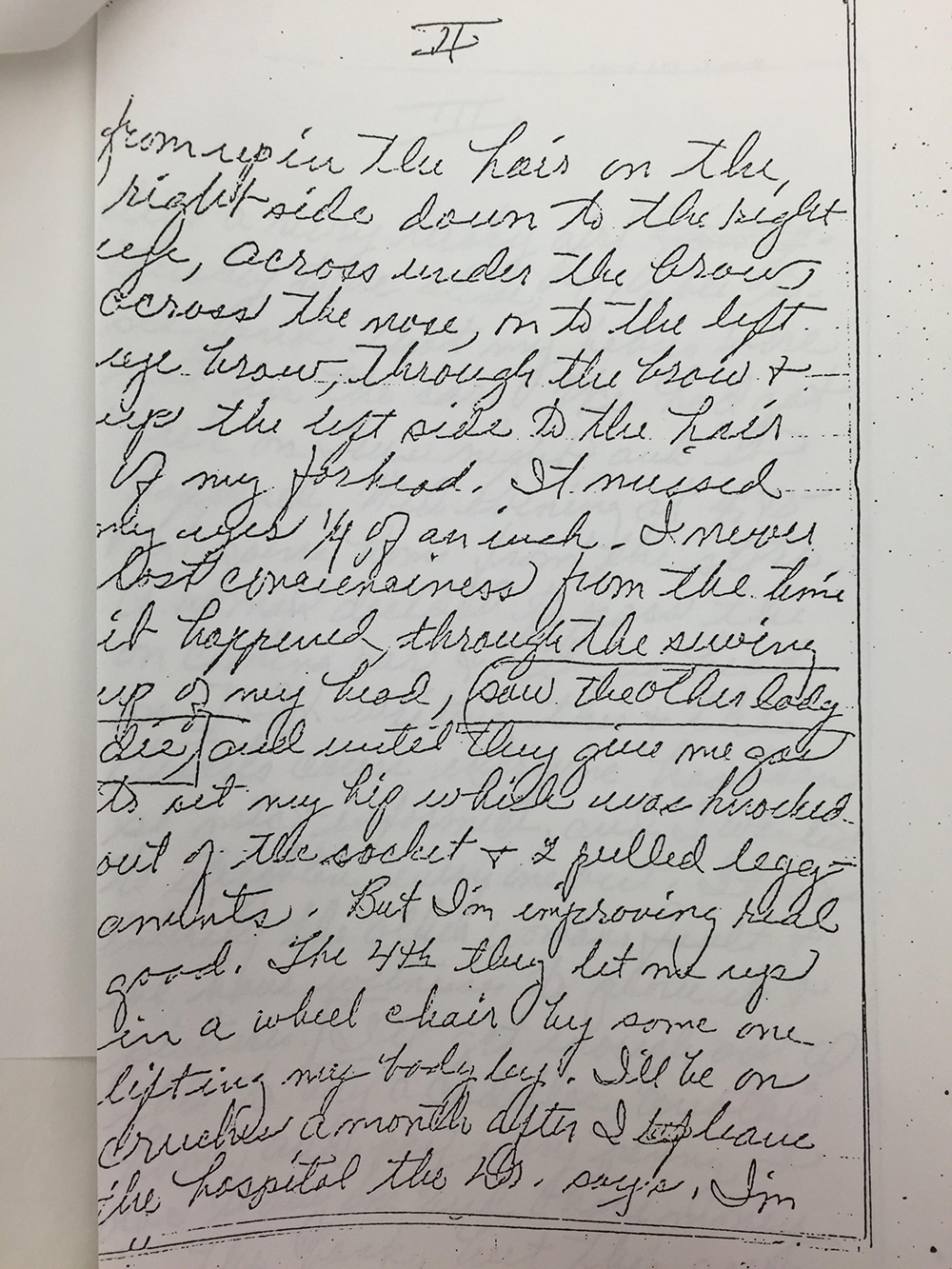

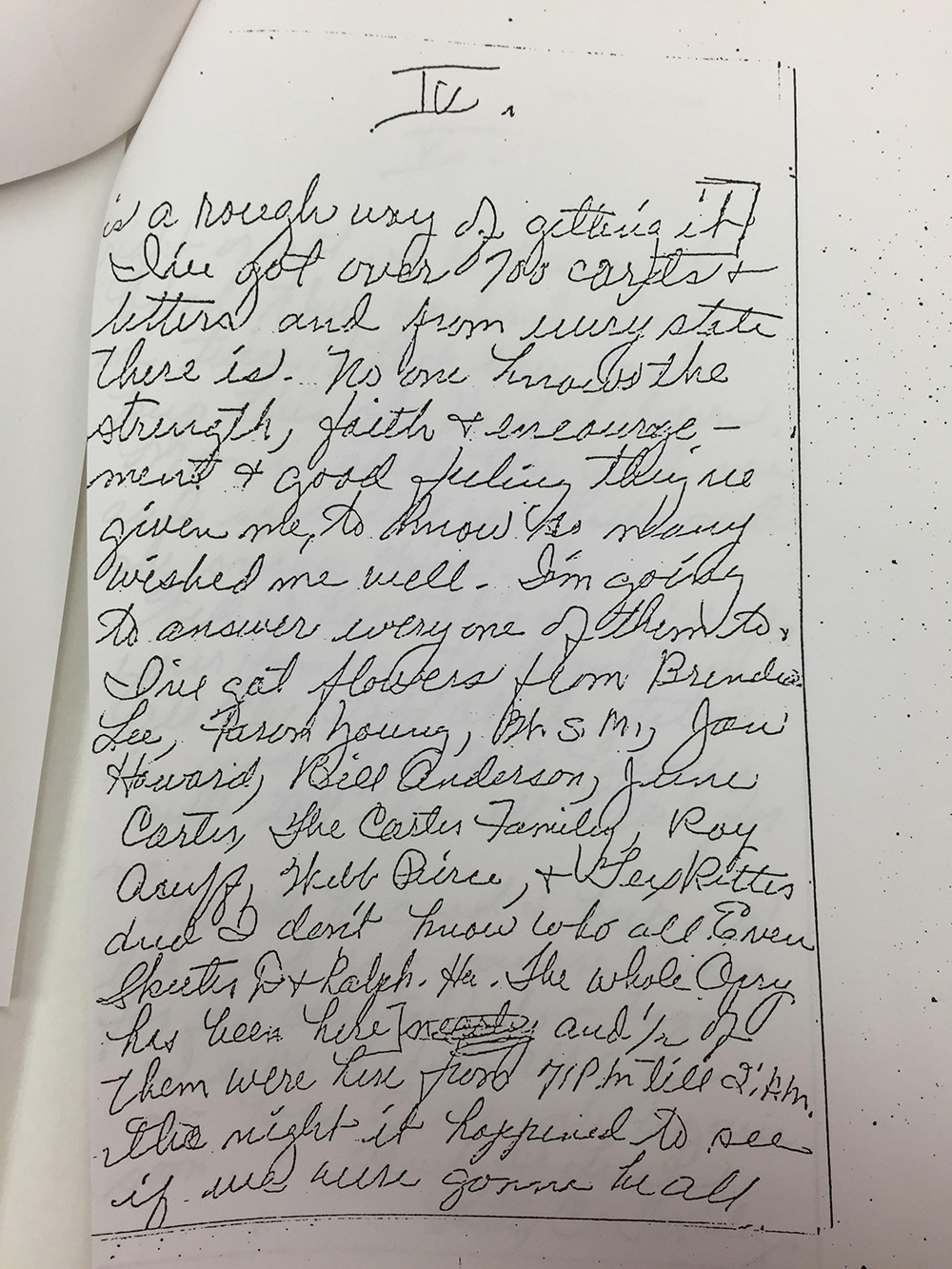

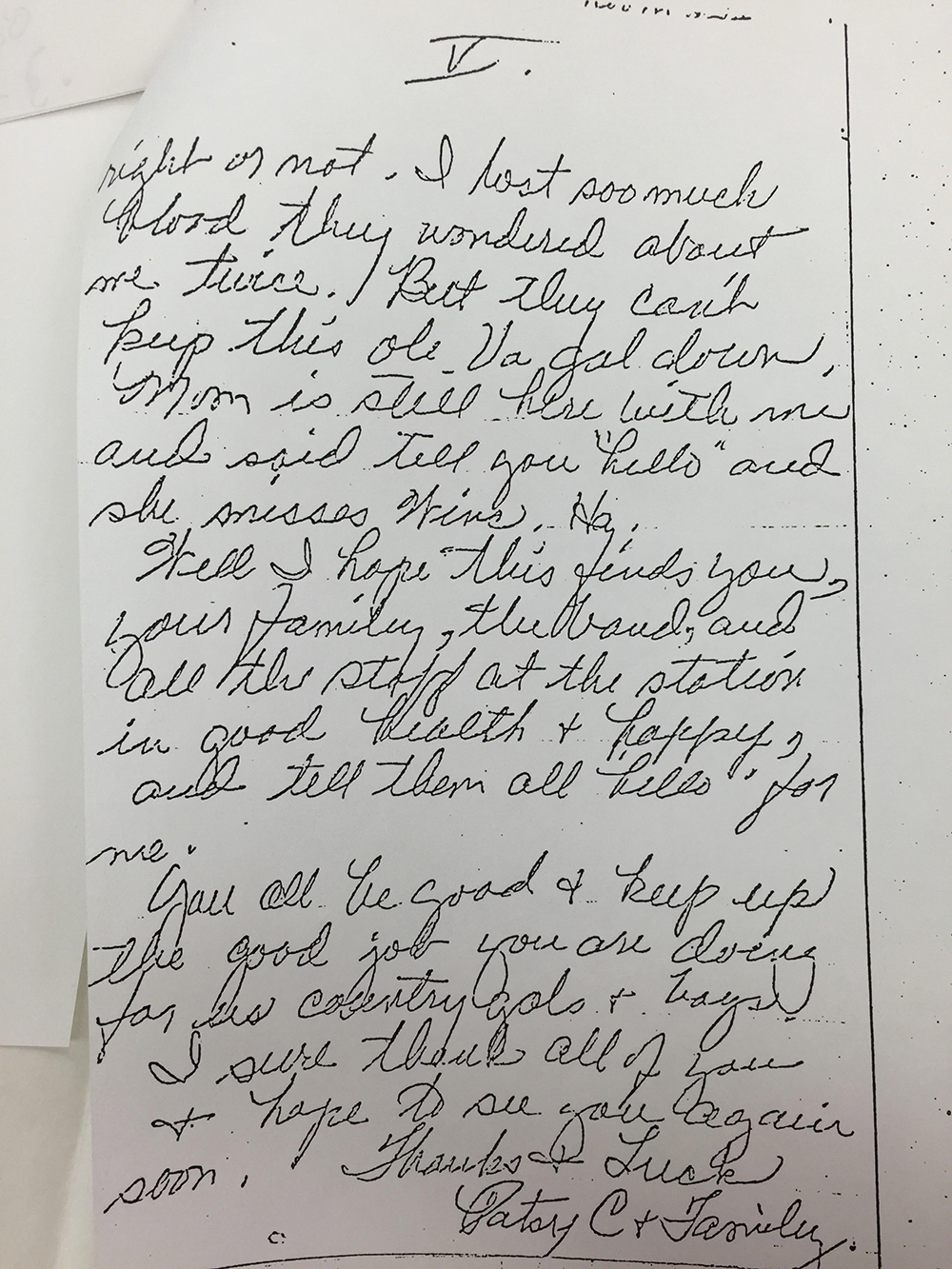

Even so, it was a special kind of thrill to find this letter, written from the hospital and addressed to Jim and his family. It’s available only as a photocopy in the archives of the Handley Library in downtown Winchester, but even in that one-degree-removed state, her vaunted charm and perseverance come through. “I hope you can read this,” she writes in perfect script,

I've got my right arm in a splint because my wrist is cracked...I was cut (by the windshield) from up in the hair in the right side down to the right eye, across under the brows, across the nose, on to the left eye brow, through the left side to the hair of my forhead [sic]. It missed my eyes 1/4 of an inch.

She itemizes the other traumas: her hip popped out of its socket, her brother John received a three-inch puncture in his breastbone and broken ribs, and she watched the other driver die at the scene.

Nevertheless, she’s upbeat, having received countless visits from her more famous peers at the Grand Ole Opry and hundreds of fan letters. “They can’t keep this ole Va. girl down,” she writes. When she eventually lost her life, her legend only grew among her fellow working-class Winchesterites, and this document, more than a thousand testimonials from old friends, shows why she was so beloved.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Nicholas Smith, author of Kicks: The Great American Story of Sneakers

• Emily Ogden, author of Credulity: A Cultural History of U.S. Mesmerism

• Anna Clark, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Philip Dray, author of The Fair Chase: The Epic Story of Hunting in America

• Elaine Weiss, author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

• Daegan Miller, author of This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing