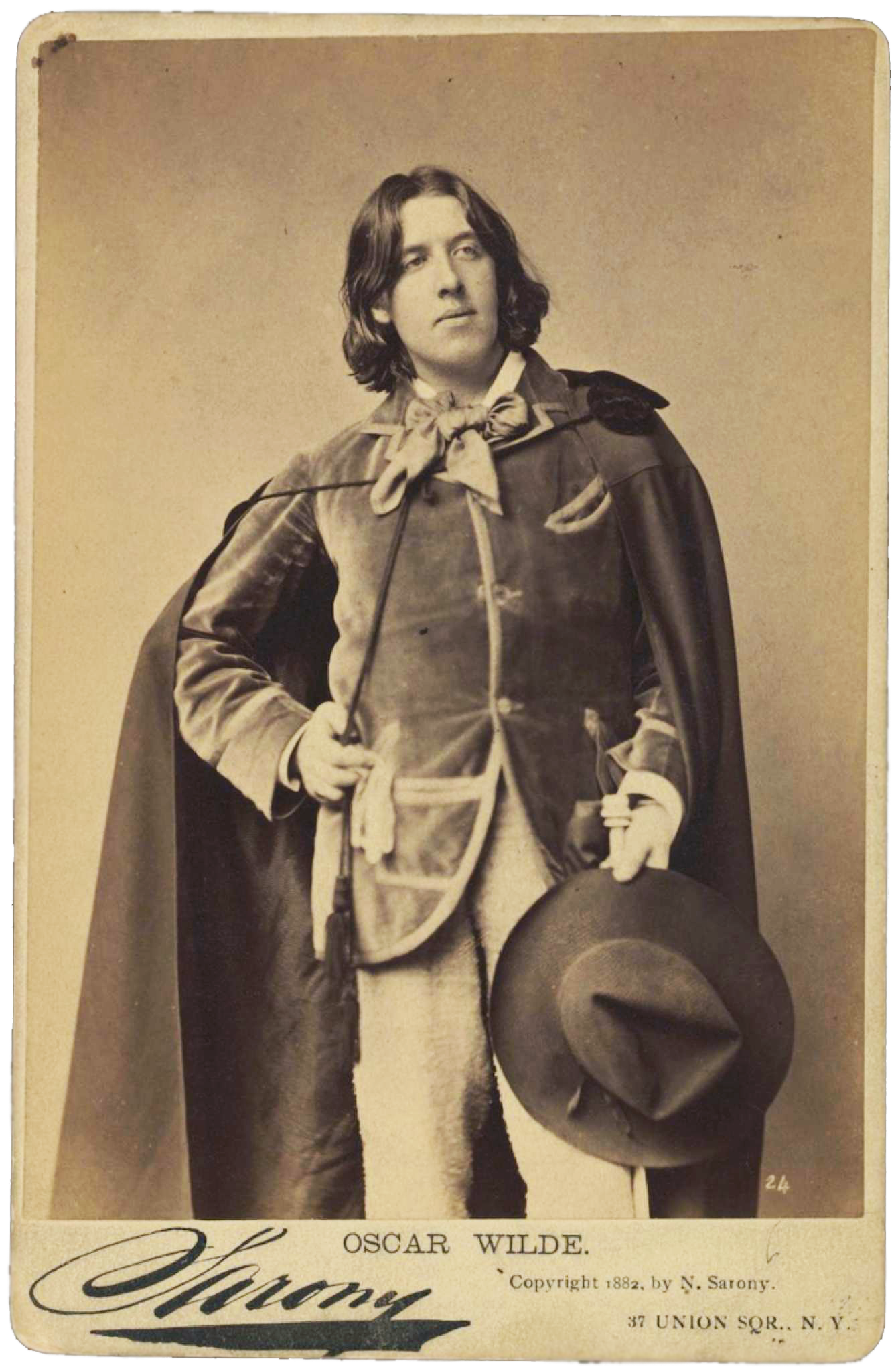

Oscar Wilde, by Napoleon Sarony, albumen silver print, 1882.

On Christmas Eve, 1881, Oscar Wilde boarded a steamship at Liverpool and disembarked in New York City on January 3, proceeding over the next year to travel fifteen thousand miles across North America by carriage, boat, and train, delivering more than 140 lectures, sitting for at least ninety-eight interviews, and becoming the subject of more than five hundred newspaper articles. Wilde gave talks on aestheticism and interior decorating at the Music Hall in Boston, Platt’s Hall in San Francisco, the Pavilion in Galveston, and the Academy of Music in Halifax. He drew crowds ranging from twenty-five to 2,500, made up variously of socialites, intellectuals, housewives, students, prospectors, prostitutes, and Texas Rangers. Along the way he met, drank, or supped with Walt Whitman, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ulysses S. Grant, Jefferson Davis, Louisa May Alcott, and Henry James. In terms of scope, pace, and publicity (generated and attracted), the lecture series surpassed both of Charles Dickens’ American reading tours. Wilde was twenty-seven years old.

What makes this extensive tour even more incredible is that the author of A Picture of Dorian Gray, An Ideal Husband, and The Importance of Being Earnest wasn’t much of an author in 1881: the sole published book to bear his name was a volume of verse—dismissed by one reviewer as “Swinburne and water”—that Wilde had printed at his own expense. So how and why did this foreign nobody come to America with such fanfare and go on to become one of the most-quoted somebodies of the nineteenth century? This is a question raised in Roy Morris Jr.’s 2013 book Declaring His Genius: Oscar Wilde in North America and wonderfully answered in David M. Friedman’s 2014 book Wilde in America: Oscar Wilde and the Invention of Modern Celebrity. While Wilde was a decade away from writing his famous novel it seems he already knew in his heart—and his American adventure embodied—one of its best lines: “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.”

Before Wilde was a foreigner in America, he was a foreigner in England: he left off his studies at Dublin’s Trinity College to enter Oxford University in 1874. Among the Eton and Harrow boys, the latest blossoms on illustrious family trees, Wilde was decidedly Irish and comparatively middle class. To him, there were the only two options available to any stranger in a strange land: play up the differences or scrub them away. He chose the former, since one must first become part of the crowd if one later wants to stand apart from it. Wilde lost his accent, clothes, and sideburns, purchasing the evening wear, neckties, and tweed jackets that matched those of England’s finest native sons.

Wilde hosted Sunday-night parties where he showed off the reproductions of Pre-Raphaelite paintings on his walls, the blue china in his cabinet, the imported tobacco on his table, and, most of all, himself. He flitted about the room, reciting Euripides in ancient Greek, quoting Romantic poets, and trying out his latest one-liners. At the end of one such evening, a friend asked, “What is your real ambition in life?” Wilde replied, “Somehow or other I’ll be famous, and if not famous, I’ll be notorious.” Notoriety came when one of his remarks—“I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china”—was condemned by a local clergyman as “a form of heathenism.” The quip, but more importantly word of its denunciation, made him a big man on campus. He now enacted his metamorphosis—shedding the cocoon of his conformist Oxford outfit for an aesthete’s attire: baggy pants, billowing white shirt, and dark cloak; his long, shaggy hair flowed from a head that he perpetually held, as a classmate put it, sideways “like a lily bloom too heavy for its stalk.” He was an apostle of aestheticism, preaching that the beauty in art must color the drabness of everyday life—flowers in the lapel, ornamented furniture around the house, blue china at tea time, and art for art’s sake everywhere. Wilde ended up taking two firsts in classics, winning the favor of the dons John Ruskin and Walter Pater, and receiving the Newdigate Prize for poetry. Off-campus at a London society party, he made a splash big enough that when librettist W. S. Gilbert heard Wilde had won the coveted poetry prize (Ruskin and Matthew Arnold were former recipients), he sneered, “I understand that some young man wins this prize every year.” This was Wilde’s cocktail of success: see and be seen conspicuously; talk well and be talked about incessantly.

Operating out of a London house post-graduation, Wilde worked hardest on his public performances at parties, the poses he struck and the lines he delivered at them: “True friends stab you in the front,” “I can resist everything except temptation,” and “Nothing succeeds like excess.” His witticisms, costumes, talent for ingratiation, and court-holding made him a Punch cartoon called Oscuro Wildgoose; a subject among many more famous ones in William Powell Firth’s painting A Private View at the Royal Academy (book in hand, lily in lapel); and the partial basis for a lead character in Gilbert and Sullivan’s new operetta satirizing the aesthetic movement, Patience; or Bunthorne’s Bride. (Bunthorne sings that to be an aesthete, “You must lie upon the daisies and discourse in novel phrases of your complicated state of mind, / The meaning doesn't matter if it’s only idle chatter of a transcendental kind.”)

All of this probably didn’t exceed his wildest dreams; what happened next just might have. The show’s producer, Richard D’Oyly Carte, wanted it to be a hit on the other side of the Atlantic—as The Pirates of Penzance had been—but, worrying the allusive jabs might fall flat on American soil, devised a plan to educate the audience on who and what was being made fun of before the show went up. D’Oyly Carte had his American business manager, Colonel W. F. Morse, ask Wilde, the ambassador of aestheticism, to give a lecture tour to coarse-minded Americans on the finer points of beauty. All expenses would be paid and half of the ticket sales would be his. If, as Wilde told a friend, “Money and Ambition” were his “great gods” than it was an offer he could not refuse.

While Wilde was practiced in the arts of self-promotion, he not only got by with a little help from his friends—D’Oyly Carte’s publicity department worked wonders with booking agents—but he also benefited from timing, which, as a conversationalist, he must have known was everything. The consummate American showman P. T. Barnum had already demonstrated how to market a foreigner on tour—the “Swedish Nightingale,” singer Jenny Lind—and perfected the sensation-as-substance advertising style, drawing millions to his freak-loaded American Museum. Wilde styled himself as something of a Lind, something of a Feejee Mermaid, and the press reacted to the self-begot, self-raised spectacle accordingly: one New York tabloid printed twenty-two items about him in January alone.

Wilde also keenly saw the fame-building potential in two fairly recent innovations: mass-reproducible photographs and interviews. Shortly after his first engagement at Chickering Hall—a tedious affair since Wilde had never actually delivered a lecture and in earnest explained the current artistic “English Renaissance”—Wilde lit out for Napoleon Sarony’s Manhattan studio. As the country’s leading portrait photographer, Sarony had made the French actress Sarah Bernhardt a household face for her tour of the U.S. in 1880. A shot of Wilde perfectly posed and lavishly costumed would sell well in stores but more to the point would travel in advance of him as promotional material: Wilde even asked D’Oyly Carte to have lithographs of them made for cheap distribution in small cities. Through the Sarony photographs, Wilde became one of the most recognizable people in America: his old trick of see and be seen conspicuously.

As for talking well and being talked about incessantly, Wilde granted nearly every interview that was asked of him, filling hundreds of column inches in papers as disparate as the Charleston News and Courier and the Omaha Weekly Herald and swelling ticket sales in the process. Dickens hadn’t sat for a single interview on his 1867 tour, but by 1874 Mark Twain was complaining: “You know it is the custom, now, to interview any man who has become notorious.” In The Portrait of a Lady, published months before Wilde’s arrival, Henry James made Henrietta Stackpole a writer for the New York Interviewer: one character says that to read it will lead to the loss of “all faith in culture.” The sharpest interview, with regard to both parties, ran in the Boston Globe early during Wilde’s tour. “Interviewers are a product of American civilization,” he correctly observed. “You gentlemen have fairly monopolized me ever since I saw Sandy Hook,” adding that “American papers are often a screed of falsehoods.” (Different papers listed his height as anywhere from 5’3” to 6’4” and mocked him as an “ass-thete,” a “Sissy,” and a creature more ape than man.) The Globe interviewer listened to Wilde’s sound and fury and then ventured an aside: actually Wilde “very well understood the advantage of free advertising, and didn’t much care whether he was represented or misrepresented, as long as he was far from a failure as at present.”

Nothing succeeds like excess, and Wilde’s now-honed theatrics put him far from failure: in Louisville, for example, he packed the house despite competition from Barnum’s own “parlor entertainment” offered by a verifiably twenty-five-inch-tall marvel of a man named General Tom Thumb. Wilde earned an invitation to spend three weeks speaking in California for an extra $5,000 (equivalent to $115,000 today). His stint in San Francisco inspired one of America’s own most quotable satirists, Ambrose Bierce, to call Wilde in print the “sovereign of insufferables” who blew “crass vapidities through the bowel of his neck.” Nonetheless, Wilde kept going: he went to Salt Lake “because it was the first city to give a chance to ugly women”; drank whiskey with miners in a mine in Leadville, Colorado; arrived in St. Joseph, Missouri, a day after Charles and Robert Ford were hanged for the murder of Jesse James; ate dinner in Beauvoir, Louisiana, with former president of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis, who the next day told his wife, “I did not like the man”; and gave nine talks in ten days in Canada. He finally returned to New York, staying for ten weeks and offering one last lecture. Not long before he was set to sail, Wilde was swindled by a notorious con artist in a game of banco to the tune of $1,100 (he was able to cancel payment on the checks). His steamship left two days after Christmas 1882. The lecture tour made Wilde the best-traveled visitor to the U.S.—the foreigner saw more of the country than most all its natives had—as well as the most written about Briton in the land, including Queen Victoria.

Back in England in the fall of 1883—after his first produced play, Vera; or the Nihilists, flopped—Wilde decided another tour was in order, this time a local one, and he soon debuted “Personal Impressions of America.” Witty and charming if a little uneven, the talk is the best record of what Wilde may have learned from his long strange trip. About Niagara Falls: “Every American bride is taken there and the sight of the stupendous waterfall must be one of the earliest, if not the keenest, disappointments in American married life.” In a Western saloon: “I saw the only rational method of art criticism I have ever come across. Over the piano was printed a notice: Please do not shoot the pianist. He is doing his best.” On a porch in the South: “‘How beautiful the moon is tonight,’ I once remarked to a gentleman who was standing next to me. ‘Yes,’ was his reply, ‘but you should have seen it before the war.’” And of the nation: “America is the noisiest country that ever existed.”

Only into a few of his later works did Wilde sprinkle salty bits about America, such as his statement in an essay, “We have really everything in common with America nowadays, except, of course, language” and Lady Hunstanton’s question in A Woman of No Importance, “When bad Americans die, where do they go to?” to which Lord Illingworth’s replies: “Oh, they go to America.” Such lines and the lecture aside, it’s hard to judge the impact America had on Wilde or Wilde had on America. But Wilde certainly satisfied America’s insatiable need for spectacle, lending to the country the presence of an undeniably singular personality—the dandy in a purple velvet coat read aloud passages from Benvenuto Cellini’s autobiography to a group of pistol-packing cowboys—and America satisfied Wilde’s insatiable need for money and attention. The tour also launched his career as a product intended for consumption, teaching him perhaps the most lasting lesson of his life: the importance of being Wilde. He would forever be a man and a one-man show. Wilde left America knowing that the whole world was now his stage: and since the play was poorly cast, he did not cease from acting and acting out for the rest of his life.

Further Reading:

Wilde in America, by David M. Friedman (W. W. Norton, 2014)

Declaring His Genius, by Roy Morris, Jr. (Belknap Press, 2013)

Oscar Wilde in America: The Interviews, edited by Matthew Hofer and Gary Scharnhorst (University of Illinois Press, 2010)