A real leader is somebody who can help us overcome the limitations of our own individual laziness and selfishness and weakness and fear and get us to do better, harder things than we can get ourselves to do on our own.

—David Foster Wallace, 2000Tales of Brave Ulysses

Ulysses S. Grant was overlooked by historians and underestimated by contemporaries. H.W. Brands reevaluates Grant’s presidency.

By H.W. Brands

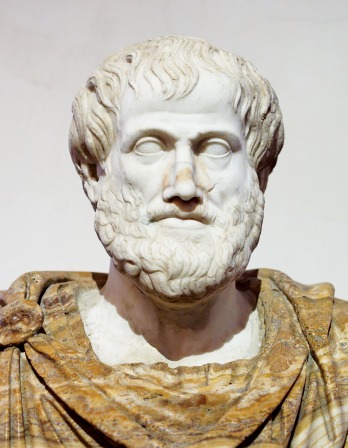

Official White House portrait of President U.S. Grant, by Henry Ulke, 1875.

History’s judgments are never definitive. If they were, historians would run out of things to say. The story of our past is always a work in progress, an endless torrent of writing and revision. Thomas Jefferson was the Antichrist to his Federalist contemporaries, a demigod to several succeeding generations, a hypocrite to civil rights advocates of the 1960s, and various other things since. Theodore Roosevelt was simultaneously the scourge of the Democrats in his day and a wild-eyed radical to Wall Street (J.P. Morgan reportedly toasted the success of the lions when TR went off on a postpresidential safari), but he became a bipartisan favorite in the late twentieth century. The changing views of historical subjects reflect new information—Jefferson traditionalists are having an ever-harder time denying the DNA evidence that Jefferson fathered children by his slave Sally Hemings—but also the evolving attitudes of those viewing the past. Each generation finds the heroes it needs.

Ulysses S. Grant was a hero to his generation: the greatest general of the Civil War, a popular president who was elected twice—and could have been elected three or four times had he wished. But later generations found him entirely dispensable, and he became the butt of historians’ jokes. Surveys of presidential scholars long placed Grant among the worst presidents. In a 1948 poll he rated ahead of just Warren Harding; by 1982 he had only clambered past James Buchanan and Andrew Johnson. And while today he has managed to put a little more distance between himself and last place, it is still no surprise to find him in the bottom half, if not among the bottom ten.

The standard rap on Grant is that he was a drunk who surrounded himself with spoilsmen who stole the country blind. In an era of scandals—the Crédit Mobilier’s siphoning of millions in the construction of the transcontinental railroad, the Tweed Ring’s bilking of New York in awarding city contracts, the Whiskey Ring’s dodging of the tax on booze—Grant was said to turn a blind (or drunken) eye to all manner of wrongdoing. Beyond that, the simple soldier was over his head in the White House. At a time of rapid economic change, he hadn’t a clue how to manage an increasingly sophisticated economy.

Considering the current state of the American economy, this last charge might now be the most damning, if true. But it’s not true. And Grant’s surprisingly sophisticated handling of economics, especially in the wake of the Panic of 1873, suggests that he deserves better from the historians than he has been getting.

The Panic of 1873 began like every other financial panic. Certain speculations were too tempting to resist; investors told themselves that this time things were different. The law of gravity no longer applied; what was going up would not come down. On occasions past, the temptations had been tulips and western land; now it was western railroads, which would tame the wild Indians, fill the frontier with farmers, and return profits from their traffic for decades. The premise was sound; the West would indeed yield profits for the railroads far into the future. But the profits did not come soon enough to redeem the extravagant promises made in their name. In September 1873 the Philadelphia firm of Jay Cooke, the financier who during the Civil War had sold a billion dollars in bonds that fed, clothed, and armed the soldiers of the Union, shuttered its doors. Jay Cooke & Co. had undertaken to underwrite the Northern Pacific Railway, which it pitched as the gateway to the Eden of the Pacific Northwest. But some invisible tremor, some inaudible signal caused investors to shy at the bonds, and the firm suddenly couldn’t meet its commitments.

As in other panics, the failure of one firm caused others to collapse. In the 1870s, in the infancy of American industrial capitalism, there were no government agencies to intervene, no safety nets to keep the falling rubble from crushing the innocent on the sidewalks below. Banks by the dozen became illiquid and then insolvent. Depositors lost their shirts and then their trousers. Wall Street seized up; the Stock Exchange suspended business for more than a week. Railroads, the largest corporations in America, laid off tens of thousands of workers before throwing themselves upon their creditors’ mercy. Factories furloughed whole shifts; merchants cleared inventories and refused to reorder.

The country experienced something new in American history: a full-blown national depression. Previous downturns had been modest in degree and regional in scope. When most Americans were farmers, their exposure to the vagaries of the market was limited. They could eat their produce if they couldn’t sell it; they could live in their farmhouses even if the farms faltered. But as the capitalist revolution kicked into high gear during the Civil War, Americans—native-born and immigrant—increasingly took jobs in mines and mills. The jobs paid better than farm labor but subjected the workers to forces over which they had no control. Those forces drove the economy and the nation in a downward spiral after the Panic of 1873, until millions were without work, without homes, without hope, without a clue as to how this all had come about.

Nothing in Ulysses Grant’s background gave a sign that he might know what to do. His West Point education had covered engineering, mathematics, and history but included precious little on economics, finance, or business. He had served as quartermaster during the Mexican War, but doling out rations to a regiment was a far cry from overseeing a national economy. His few business ventures after the war had flopped, to the dismay of his father, who did know a thing or two about commerce. The Civil War had drawn Grant back into the army, where he excelled at the soldier’s mission of breaking things and killing people, but policy matters he left to the elected officials.

The panic and the ensuing depression were accompanied by plunging prices for all manner of goods and services. Grant knew enough economics to realize that the falling prices were both a cause and a consequence of the depression. With prices falling, potential purchasers had reason to delay their purchases, and the delay added to the downward pressure on prices. Grant understood that the government might mitigate this vicious cycle by expanding the currency, that is, printing more money. The new dollars would tend to boost prices, and the vicious cycle could turn virtuous.

Franklin at the Court of France, 1778, Receiving the Homage of His Genius and the Recognition of His Country’s Advent Among the Nations, painted by Baron Jolly and engraved by William Geller, 1853. © Boston Athenaeum, The Bridgeman Art Library.

There were consequences, though. The American government had never intervened in the economy in such a deliberate and sustained way. A decision to expand the currency would affect everyone in the country and, to be effective, might have to be repeated. Its very effectiveness, moreover, would create expectations of rising prices, which might easily spin out of control. A little inflation would help the economy, but no one knew whether there could be such a thing as a little inflation.

Congress was willing to take the risk. With their 1874 elections looming, members wished to appear to be addressing the economic crisis, and the legislature that spring passed a bill, commonly called the Inflation Bill, that would significantly expand the currency.

The bill landed on Grant’s desk, giving him the choice of approving or vetoing it. Grant generally took the originalist view of the veto power: that a president should reject only those measures he deemed unconstitutional. And so he tried to talk himself into accepting the Inflation Bill. He drafted a memo explaining the bill’s positive attributes. First, the country had been led by the bill’s passage to expect an expansion of the currency; for the president to veto it would overturn those expectations and risk stifling a recovery. “Trade and commerce would remain paralyzed,” Grant wrote. The bill included bank reforms that would free sound rural banks from their dependence on more-leveraged city banks. “Much of the trouble through the panic of last fall was no doubt due to the fact that three-fifths of the reserve of country banks were locked up in the city banks when they suspended.” Critics called the Inflation Bill a triumph for farmers and workers over capital. “In reality,” Grant rejoined, “the measure is a compromise between the two, and in my judgment is the best compromise for all occupations and sections likely to be attained.”

But try though he might, Grant couldn’t convince himself. Deliberate inflation simply struck him as wrong. So he tried making the opposite argument. The inflationary theory behind the bill was an untested novelty, he wrote in a draft veto message. “The theory in my belief is a departure from true principles of finance, national interest, national obligations to creditors, congressional promises, party pledges—both political parties—and of personal views and promises made by me in every Annual Message sent to Congress, and in each inaugural address.”

Grant, with others of his generation, had seen what paper money had done to the Confederacy, which couldn’t stop printing the stuff. The Union had survived its own experiment with paper money, but it couldn’t count on doing so forever. Gold had been the standard of money in the United States since the nation’s founding, with silver an adjunct, but under the duress of the Civil War the Republicans who controlled the federal government authorized the issue of fiat money—paper currency, printed in green ink and hence dubbed “greenbacks,” which held its value only by virtue of the government’s resolve not to print more of it. “Paper money is nothing more than promises to pay,” Grant said. And under political pressure those promises might be worth very little.

He was lobbied by both sides on the issue. But he kept his own counsel until the end, ultimately finding his second thoughts more persuasive than his first. Unwilling to embrace the novel theory of fiat money and entrust the money supply to politically vulnerable legislators, he vetoed the Inflation Bill.

His decision delighted conservatives and creditors. “God Almighty bless you!” wrote Edwards Pierrepont, who would become Grant’s attorney general. “The bravest battle and the greatest victory of your life!” But inflationists and debtors, including many who had revered Grant for his war service, now condemned him for bending to the big bankers. “It is an insult to the virtue, intelligence, honor, and patriotism of the people of this nation,” a spokesman for the merchants of Indianapolis declared, “to have a few of those, whose god is the dollar, to go with brazen impudence and flaunt in the face of the people’s chief executive officer the fact of their great wealth, and it is utterly shameful that that chief executive should bow at their behests and do their bidding.”

But the veto stuck. And the following year Congress approved the Resumption Act, which specified a timetable for retiring the greenbacks and returning the country to a gold standard. Perhaps coincidentally, perhaps not—causation in economics being as hard to prove as causation in most human activities—the return to gold was accompanied by a return of the country to prosperity.

Grant’s encounter with the money question is a reminder that most things new are old. Today, Paul Krugman advocates a policy akin to that of the inflationists of the 1870s, and Ron Paul and his acolytes cry for a return to gold. Ben Bernanke finds himself in much the same position that Grant was in. To inflate or not to inflate: that is the question now just as it was in 1874.

Now, as then, the arguments are couched in terms of what is good for the country. But now, as then, the arguers see the good of the country as their own good writ large. Creditors loved Grant for doing what benefitted them and thought it benefitted the country; debtors denounced him for ignoring them and, with them, the country. Even in hindsight it is difficult to tell whether his action did serve the country. A fair judgment on Bernanke’s policies comes harder still.

Grant emerges from the inflation episode a more subtle thinker than he was deemed by contemporaries and most historians since. He took office at a time when the Republican party was having to face its divided nature. The party had commenced life as a coalition of Free-Soilers and erstwhile Whigs; the former stressed opposition to slavery, the latter government support for business. The two wings—the conscience wing and the capitalist wing—had cooperated until the end of the Civil War, which simultaneously destroyed slavery and catapulted capitalism to the ideological high ground it has held in America ever since. But at the war’s end their ways diverged. The conscience Republicans, who stressed social issues, thought the party ought to focus on completing emancipation by securing the rights of the freedmen against reactionary Southerners, while the capitalist Republicans wanted to do business—literally—with those Southerners, even if it meant sacrificing the freedmen. Grant was chosen as the party’s standard-bearer in 1868 because, as the war’s great hero, he could ensure victory and because each side hoped he would stand with them. He was shrewd enough to keep his mouth shut until after the voting. “Let us have peace,” he said in his letter accepting the Republican nomination, and little more.

O citizens, first acquire wealth; you can practice virtue afterward.

—Horace, 8 BCHis silence fed a feeling that he wasn’t very smart. Combined with the longstanding stories that he drank too much—stories based on actual but rare benders that never interfered with his work—he appeared to the party’s pros a man they could manipulate or maneuver around. But he hadn’t bested every general the Confederacy sent against him to be defeated by mere politicians. He declined to defer to Charles Sumner, the Massachusetts senator who had been caned to within an inch of his life by Preston Brooks in the 1850s and who fancied himself the one true guardian of African Americans. Sumner denied Grant credit for aiding the freedmen—ignoring that Grant had won the war and thereby put teeth in Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation—and he became a thorn in the administration’s side. Sumner was joined by Carl Schurz, the German radical who had fled the failed revolution of 1848 and sailed to America, where he wound up a Union general and then a senator from Missouri. Like Sumner, Schurz thought Grant unworthy of the mantle of Lincoln, and in 1872 he and others of like mind tried to reconfigure the Republican party as the Liberal Republicans, with someone besides Grant as nominee.

Grant proved a better politician than his opponents, and more determined. He recognized that the only beneficiaries of the Liberals’ secession would be the Democrats, who remained beholden to the same Southern conservatives who had brought on the Civil War. Grant had never been an eager candidate, but he refused to let the Democrats win at the ballot box what they had lost on the battlefield, and he trounced the Liberals, who never forgave him.

The complaints of the Liberals constituted the first draft of the history of the Grant administration. They ignored or, unaccountably, condemned Grant’s stern actions against the Ku Klux Klan, which included persuading Congress to give him authority to suspend habeas corpus and send the military against the race terrorists. Grant employed the authority, dispatched the troops, arrested hundreds of Klansmen and sympathizers, scattered thousands more, and rendered the organization a nullity. But the Liberals lamented his reliance on force, apparently preferring measures more genteel. They taxed him for the corruption of a few of his executive appointees and, by extension, for the much grander larcenies of Crédit Mobilier and Tammany Hall, with neither of which he had anything to do. They blamed him for not sharing their distaste for the rising capitalist class that was displacing them in the esteem of the country. Henry Adams felt the displacement most personally, being the underperforming great-grandson of one president and the grandson of another—and a person who spent his whole life befuddled by the process of industrialization. Adams took out his frustration and befuddlement on Grant, whom he judged utterly unfit to preside over the American republic. “The progress of evolution from President Washington to President Grant was alone evidence enough to upset Darwin,” he declared with characteristic dyspepsia.

Despite the alienation of the intellectuals, Grant never lost touch with the people, who continued to revere him for his wartime service and admired him as a common man who never forgot his roots. He most likely could have been elected a third time, in 1876, had he merely given the nod. But he stepped down and left the country on a world tour, which lasted over two years and showed him to be quite possibly the most famous and beloved person on earth at that time. Crowned heads of state hosted him; workers hailed him; governments vied to secure his good offices. He returned to America and nearly won the Republican nomination for 1880 despite again declining to campaign.

Grant’s death in 1885 and the subsequent publication of his memoir the same year stilled the criticism for a time. Mark Twain favorably compared the book, which dealt mostly with the Civil War, with Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic War. Twain’s opinion wasn’t unbiased; he was Grant’s publisher and earned a handsome profit on the project. But the verdict has held up ever since. Nearly every president who turns memoirist claims to take Grant as a model. (Most, including George W. Bush, the latest to channel Grant, fail to appreciate that the model really works only for those who have commanded armies that won a major war.)

The denigration of Grant soon recommenced. In the wake of Reconstruction, elites in both the North and the South undertook to paper over the differences that had produced the Civil War. Southerners wanted to reclaim their primacy over a region they had led to a disastrous defeat; Northerners itched to get on with industrialization. From both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line they reached back beyond the sectional crisis to a time when the country was united against a common foe: the era of America’s founding. The end of Reconstruction coincided with the centennial of American independence; by celebrating the achievements of the Founders, the post-Reconstruction elites could construct a past that helped bury the recent unpleasantness. For Southerners the canonization of the Founders had the added merit of burnishing the pride of their section, which had given the country five of its first seven presidents.

Yet even in death Grant could still draw a crowd. The dedication of his tomb in New York in 1897 brought out hundreds of thousands to remember the Union hero. But his accomplishments fell into disregard, the more so as the soldiers who had served under him eventually died. The Southern interpretation of secession as a gallant Lost Cause suited Southerners, naturally, but also Northerners reluctant to be reminded that they were complicit in the continuing denial of rights to Southern blacks. Reconstruction was treated as a carnival of corruption on the part of Northern carpetbaggers and beastly Southern blacks; the Ku Klux Klan became, in D.W. Griffith’s sensational Birth of a Nation, brave defenders of Southern virtue. Lauded by Virginia-born Woodrow Wilson, who applied the segregating principles of Jim Crow to the federal workforce, the Griffith interpretation of Grant’s era left no room for the president who defied and defeated the Klan.

The Senate of Tlaxcala, by Rodrigo Gutiérrez, 1875. Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City.

Even when the public mind turned against the Jim Crow system, during the 1950s and ’60s, Grant’s reputation didn’t benefit much. The civil rights movement understandably emphasized what previous generations had failed to accomplish, and instead of being praised for standing up for the rights of the freedmen, Grant was criticized for finally bowing to the constitutionally inevitable and agreeing to the restoration of civilian rule in the South. “Buffeted by the shifting tides of public opinion, preoccupied first with the economic depression and later with yet another wave of political scandals, the second Grant administration found it impossible to deliver a coherent policy toward the South,” Eric Foner wrote in his 1988 Reconstruction, which remains the leading work on the subject. Moreover, the civil rights movement overlapped with the antiwar movement of the Vietnam years, and a man who became famous as a general got little respect from the peace marchers or from academics who, in protest against the Vietnam War, largely wrote off the field of military history. William S. McFeely found Grant interesting enough to write about, yet in a 1981 biography that reflected the period’s penchant for psychohistory, and which remains the starting point for Grant studies, he concluded that Grant’s historical rehabilitation was impossible. “No amount of revision is going to change the way men died at Cold Harbor, the fact that men in the Whiskey Ring stole money, and the broken hopes of black Americans in Clinton, Mississippi, in 1875,” McFeely wrote, referring, in the last instance, to the violence-scarred return of Democrats to power in Mississippi.

But gradually America’s growing conservatism had an effect. When Foner and McFeely wrote, it was still possible for liberals, including most academic historians, to believe that the federal government could accomplish whatever it put its mind to. The failure of Reconstruction, therefore, was a failure of the leaders of Reconstruction, beginning with Grant. But as Ronald Reagan’s message of government’s inherent ineptitude sank in, Grant appeared less culpable. And as the effects of Vietnam on the American psyche faded, the fact that he was a general didn’t seem so blameworthy. The historian Geoffrey Perret, writing on Grant in 1997, praised him as a great general and, on balance, not such a bad president. Jean Edward Smith in his 2001 biography agreed with Perret on Grant’s military career and was even more complimentary of his presidency.

There will be no final verdict on Grant. How we view him will always depend, at least in part, on what we expect from American democracy. But as the problems of governing America in the present grow ever more obvious, students of the past will probably show still greater sympathy for what he confronted during one of the most difficult periods in American history. “I have acted in every instance from a conscientious desire to do what was right, constitutional, within the law, and for the very best interests of the whole people,” Grant said in his last message to Congress. “Failures have been errors of judgment, not of intent.” Many Americans today wish they could say the same about our current leaders.