To place oneself in the position of God is painful: being God is equivalent to being tortured. For being God means that one is in harmony with all that is, including the worst. The existence of the worst evils is unimaginable unless God willed them.

—Georges Bataille, 1957Church & State in America

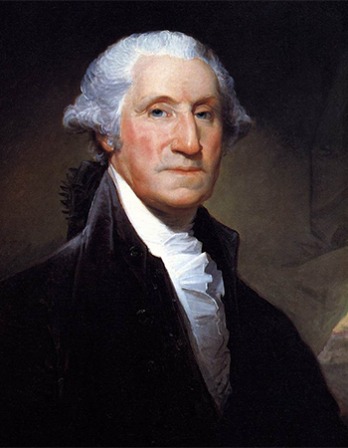

The Founding Fathers approached the church-state conundrum with an intellectual clarity that was characteristic of their times.

By Elisabeth Sifton

General George Washington Resigning His Commission, by John Trumbull, c. 1824.

In Germany in 1799, just eleven years after the Federalist Papers appeared in America, the Protestant theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher wrote a marvelous book entitled On Religion: Speeches to Its Cultured Despisers. He observed, in his high-spirited opening lines, that for a long time “faith has not been every man’s affair,” that only a “few have discerned religion itself, while millions, in various ways, have been satisfied to juggle with its trappings. Now, especially, the life of cultivated people is far from anything that might have even a resemblance to religion.” Teasing his sophisticated audience for their hostility to the subject—“I know how well you have succeeded in making your earthly life so rich and varied that you no longer stand in need of an eternity … You are agreed, I know, that nothing new, nothing convincing can any more be said on this matter”—he nonetheless plunged in.

Schleiermacher knew little of religion in the New World, but his comments hit very near the mark for America, then and now. And although our Founding Fathers didn’t know his sermons (which weren’t translated into English for almost a century), they might well have recognized some of the issues as Schleiermacher saw them. All these modern pioneers approached the church-state conundrum with a brilliant intellectual clarity and emotional, spiritual depth that was characteristic of their times. Those early years of our republic were years when religion’s place in society was explored profoundly on both sides of the Atlantic—in contrast to the loud but superficial rhetoric dominating the debate today—and we would do well to recall the terms they used and to consider the issues in the light of that epoch.

The Vision Legend of the Fourteenth Century, by Luc Olivier Merson, c. 1872. Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, France.

Let me first state my dubious credentials for writing on this subject. I think of myself as a Christian or, to use W.H. Auden’s impeccable response to the question as to whether he was one, “Well, I’m trying to be.” I grew up in the precincts of an interdenominational Protestant seminary, and though I was christened and confirmed as an Episcopalian, I attended many kinds of church service in my youth; I learned from my elders and betters that it was best to speak with courtesy to or about other Christians and non-Christians whatever their sect (I didn’t yet know how rare this was). I’m still a devout reader of the Gospels but now almost never go to church, having developed an allergy to the pious self-congratulatory tone that permeates so many of them. So I live as a skeptic and doubter, my view of churches afforded from both the familiar inside and the disaffected outside. Still, I hope I understand the wisdom of the words spoken by the man who brings his ailing son to be healed by Jesus and is instructed to believe. “Lord, I believe,” he answers, “help thou my unbelief.” Plenty of Americans find themselves in this in-between territory.

In college, as a student of the French and Scottish Enlightenments, I was enraptured by the ideas advanced by Descartes, Hume, Locke, Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot—ideas which I was certain had changed the world for the better. I became a lifelong, fervent enthusiast for the Enlightenment program of ridding human society of superstition and fear, evils that from the points of view of these writers had been most powerfully propagated over the centuries by the church, with the strength of sword and gallows behind it, with royal armies, prisons, and laws supporting the ecclesia. These men wanted, instead, to get people to trust in their own judgment and the workings of their own minds.

Now, is there an inevitable contradiction between those great Enlightenment aims to advance knowledge and understanding and the enlightening goals of true religion? I don’t think so, any more than Schleiermacher did, or John Adams, James Madison, and

Thomas Jefferson. Eighteenth-century deists as our Founding Fathers were, they claimed to believe in an almighty being that had created the natural world, while they rejected the notions of “revealed religion.” Their deism gave them an honorable position from which to deal with their conventionally devout fellow citizens, the depth of whose spiritual sentiments they respected.

When the architects of our nation insisted that “All men are created equal,” they knew that adherence to this philosophical idea, respected in all religions, would require considerable political energy and skill to maintain in a modern polity. It had never been done before. They risked their lives for their revolutionary beliefs and, more than almost any group in human history, gave them embodied meaning. Their superb affirmation of the sovereignty of the people was and is thrilling; likewise their insistence that the nation’s executive, legislative, and judicial authorities should do their work—divided and balanced, so as to check against any aggregation of dictatorial power—only with the consent of the governed. I judge the United States Constitution, which gave structure and detail to these controversial ideas, and which of course also insists on religious freedom and prohibits the government from establishing a state church, as the Enlightenment’s greatest public document.

The robust lucidity with which our Founders handled church-state issues has, however, been horribly mauled of late, as debates between believers and nonbelievers over power, money, and meaning have turned both fatuous and ugly; opinions violently clash about the proper relation between our government and our religious institutions, and about the appropriate significance of reason and science in our lives—and whether they conflict or can coexist with religious belief. These disputes boil up into a battle royal about the very nature of our state and civil society. Meanwhile, superstition and fear are fed from new, sometimes secular, sources.

Yet that religion was woven into America’s national life from the start we all know well. We treasure the heartwarming foundational image of John Winthrop’s city on a hill, which President Reagan glorified by calling it a “shining” city on a hill. The theocracy of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was in fact harsh and unpretty, but the Puritans did conceive of their New World community as one directed by God’s word, and so religious commitment conjoined with our Founders’ Enlightenment faith in reason—creating the peculiar American culture that is both more religious and more secular than many other nations.

By 1776, however, a century and a half after the landing at Plymouth Rock, what do we find? George Washington went to church infrequently and rarely took Communion. Benjamin Franklin was suspicious of all organized religion. John Adams wrote to Jefferson in 1815, “The question before the human race is, whether the God of nature shall govern the world by his own laws, or whether priests and kings shall rule it by fictitious miracles?” James Madison believed that an established religion—a church whose doctrines were guaranteed and enforced by state law—did harm both to religion and to free government, and he found it abhorrent to imagine God being twisted to fit political expediency: this was, he said, to throw religion to the wolves.

The dangers in the other direction were even greater, to his mind. “What influence in fact have ecclesiastical establishments had on civil society?” Madison asked in 1785. “In some instances they have been seen to erect a spiritual tyranny on the ruins of the civil authority; in many instances they have been seen upholding the thrones of political tyranny; in no instance have they been seen the guardians of the liberties of the people. Rulers who wished to subvert the public liberty may have found an established clergy convenient auxiliaries. A just government instituted to secure and perpetuate it needs them not.” Nearly fifty years later, having experienced these issues firsthand as president (1809–1817), Madison remained steadfast in a letter written to Reverend Jasper Adams in 1832:

It may not be easy, in every possible case, to trace the line of separation between the rights of religion and the civil authority with such distinctness as to avoid collisions and doubts on unessential points. The tendency to a usurpation on one side or the other or to a corrupting coalition or alliance between them will be best guarded against by entire abstinence of the government from interference in any way whatever, beyond the necessity of preserving public order, and protecting each sect against trespasses on its legal rights by others.

In his sustained political opposition to even a hint of an established church, Madison was joined by his great collaborator Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson had another worry on this point: he hated the very idea of enforced uniformity of opinion, or coerced belief, and he rightly associated church-state alliances with it. In 1782, he wrote in Notes on Virginia:

Truth can stand by itself. Subject opinion to coercion: whom will you make your inquisitors? Fallible men, men governed by bad passions, by private as well as public reasons. And why subject it to coercion? To produce uniformity. But is uniformity of opinion desirable? No more than of face and stature … Difference of opinion is advantageous in religion … Is uniformity attainable? Millions of innocent men, women, and children, since the introduction of Christianity, have been burnt, tortured, fined, imprisoned: yet we have not advanced one inch toward uniformity. What has been the effect of coercion? To make one half the world fools, and the other half hypocrites. To support roguery and error all over the earth.

Recognizing the disastrous effects of enforced uniformity of opinion has been an admirable constant of the American political character. To my mind the finest modern expression of it can be found in Justice Robert Jackson’s 1943 opinion—written when wartime pressures to conform to America’s patriotic ideal were predictably strong—that struck down a law requiring the uniform recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance in schools (West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette); this passage from it ends with one of the greatest sentences in all of American jurisprudence:

Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard. There is no mysticism in the American concept of the state or of the nature or origin of its authority. We set up government by consent of the governed, and the Bill of Rights denies those in power any legal opportunity to coerce that consent…If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.

This noble refusal to be pushed around in matters spiritual and political is not respected by those who currently insist on a different version of the foundational story. Many pious people now claim that the first Americans were all God-fearing Christians who wanted their new nation to be ruled by God—and a high proportion of these people also happen to dislike the secular democratic liberties expressed and expanded in the Progressive Era, New Deal, New Frontier, and Great Society.

Creation of Adam (detail), Sistine Chapel Ceiling, by Michelangelo, c. 1508–1512. Vatican City, Rome, Italy.

One of the cleverest exponents of this position is Justice Antonin Scalia, known also for his vehement “originalism” in matters of constitutional law. Blithely misinterpreting two centuries of post-Enlightenment political philosophy, Justice Scalia asserts that the consensus of Western thought has been until recently “that government—however you want to limit that concept—derives its moral authority from God. Not just of Christian or religious thought, but of secular thought regarding the powers of the state. That consensus has been upset, I think, by the emergence of democracy.” The devilish secularism of modern democracy must, then, be defeated. As he puts it:

The reaction of people of faith to this tendency of democracy to obscure the divine authority behind government should not be resignation to it, but the resolution to combat it as effectively as possible. We have done that in this country (and continental Europe has not) by preserving in our public life many visible reminders that—in the words of a Supreme Court opinion from the 1940s—“we are a religious people, whose institutions presuppose a supreme being.”

Never mind that the opinion he quotes was Justice William O. Douglas’ in 1952 (Zorach v. Clauson). Douglas didn’t even try to support his vacuous assertion, but Scalia can’t (could never) prove his even more expansive notion of divine authority guiding the work of our democratic institutions, so he takes diversionary action. Look, he says, at “In God We Trust” on our coins, “the opening of sessions of our legislatures with a prayer” and of our Supreme Court sessions with “God save the United States and this Honorable Court,” “one nation, under God” in our Pledge of Allegiance, and so on. (Never mind also that the Pledge was composed only in 1892 by a secular socialist, and the “one nation, under God” phrase added only in 1954.)

I’d like to think Scalia knows that these polite deistic references to the Almighty, which have been sprinkled around the American political landscape for hundreds of years, are hardly proof of a foundational theocracy. Most Americans including energetic Christians like President Theodore Roosevelt, who opposed putting “In God We Trust” on specie—do not believe the federal government is divinely ordained and dislike the reverberant public God talk. As a Baptist pastor in Alabama wrote some years ago, “Giving lip service to God does not advance faith, it cheapens it. It takes the language of faith and reduces it to mere political rhetoric. Language that has the power to heal and mend should never be treated so callously.”

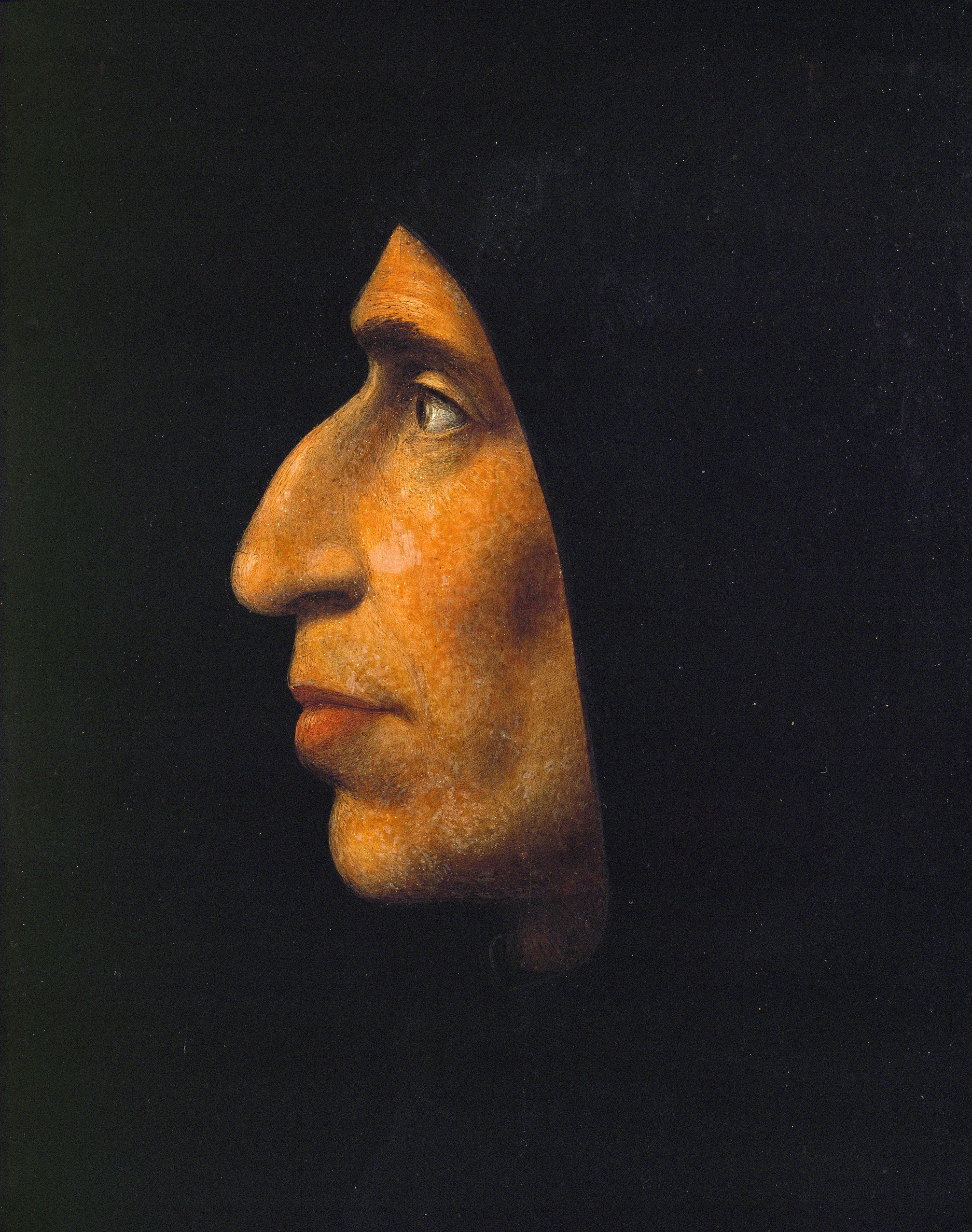

Leaving aside these rhetorical flourishes, Scalia and those who agree with him disregard the dangers the Founders warned against: the tendency of religious groups to corruption and folly when granted political power, their likely insistence on uniformity of opinion, and the subversion of public liberty consequent upon both. But in a political climate that encourages views like his, we have had to endure the increased clout of religious groups that once scorned electoral politics and now are emboldened to use them to gain power and impose uniformity of opinion on a whole range of social and political issues—gay marriage, stem-cell research, affirmative action, modern evolutionary biology and paleontology, any limitations on executive power. As Garry Wills has observed, their success has depended on a strange alliance of many small fringe organizations far from the center of American mainstream politics but encircling our national life and threatening to strangle it. These include Protestant fundamentalists, conservatives in the Catholic Church, ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities, and secular, sometimes quite violent reactionaries who join them to assault the foundational beliefs of the American nation, kidnap doctrine, and lobby for laws they like, believing they must do this whenever God gives them the opportunity.

I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who has endowed us with sense, reason, and intellect has intended us to forgo their use.

—Galileo Galilei, 1615Secular media are tempted to presume that these right-wing voices represent the views of “American religion” today, which is manifestly untrue. But what do they know? They don’t report on the many sensible clergy and congregants who deplore absolutism, who try to obey the inner counsels and outer practices of their religious commitments, live at peace with their neighbors, and honor the republic. Worse, the ultrasecular denizens of our media-driven world ignore the evidence of what one might call the spiritual temperament among rational people whether of the left, right, or center. They do not seem to grasp that making the daily effort to obey virtually impossible spiritual commands, to live in hope even under the most tragic or evil circumstances, and to do this as a “discipline of the heart”—that this practice, as Buddhists call it, is what distinguishes the genuine religious life. Among devout people of whatever sect or group, the real index of faith is measured not in the frequency of public declarations of religious allegiance, or belief in God, or trust in this or that set of historic events or “fictitious miracles” (as Adams called them), but in continual spiritual exercise, in daily contrition, in daily recommitment to what you hope is a true, decent way of life.

All the world’s religions have devised different forms of private and public worship to encourage these disciplines of the heart, tell different stories about different foundational leaders, and have committed different sins and errors, of course. But they share an understanding of the effort—all the more real for its innerness. As Schleiermacher said, “Religion…in its own original, characteristic form, is not accustomed to appear openly, but is only seen in secret by those who love it.” Respectful deists like the Founders knew this.

Since religious commitment is bound to affect a person’s professional, political, and public behavior, one can’t convincingly argue that it should be partitioned off as a private matter that has nothing to do with a person’s public conduct, as dogmatic secularists and atheists nowadays insist. Alas, many stout defenders of the principles of secular government, including some otherwise very smart judges, resort to this dead-end logic—keep religion private, don’t let it into public life, make the Founders’ wall between church and state into a wall between private religion and public politics. But the Founders, with their stronger grasp on what religion actually is, wisely did not make this extreme demand, although they understood perfectly well that the republic must defend against religion’s absolute claims intruding into what is necessarily the proximate, compromised life of politics.

Girolamo Savonarola, by Fra Bartolomeo, c. 1495. Museo di San Marco, Florence, Italy.

For the unfortunate contemporary dumbing down of the church-state debate, blame must be apportioned on all sides: not just on the sclerotic pedantry you find in modern legal squabbles on the subject, but also on pious loudmouths who favor public pledges about their faith-based commitments, and on agnostics and atheists who hold a general disregard of religion in America’s modern culture and who are proud of their hostility to the life of faith. The nuanced difficulties of reconciling religious conduct with good citizenry in a secular republic, difficulties the Founders recognized from the start, will never be resolved if the impermeable-wall standard, now so favored, is used insensitively.

And in the great American tradition, the difficulties are magnified by money. Many noisy people who insist on the inevitable conflict between the realms of reason, science, and secular government on the one hand and those of religion on the other have a vested worldly commitment—financial, bureaucratic, social—in keeping up the divide. On the faith side, we have a bewildering, broad array of voices, among them the antimodern, antirational pastors who claim they read the Bible as literal truth (to be honest, I don’t actually believe they do) and who are manifestly hostile to modern civil rights and modern science (though they have their BlackBerrys and take their flu shots, I notice). You’d think, among these last especially, given their claim to adhere to an old-fashioned sense of the holy, they’d be the first to acknowledge that America as we live and breathe it—in malls, office buildings, supermarkets, and banks; on the television screen, the Internet, and highway billboards; in stadiums and on the street—America is just astonishingly given over to the worship of Mammon. Mammon!

There was a time when prophetic voices could be heard in the land warning their flocks to keep a distance from greed, corruption, and vanity—the regrettable hallmarks, they thought, of collective life in the West’s rational, freedom-loving capitalist democracies. They fought against what they considered America’s evils and dangers: ethnic and racial fault lines, indifference to the safety and welfare of workers, lack of democracy in the industrial workplace, a politics that worsened class conflict instead of lessening it, disregard of the world beyond our borders—and all these aggravating the threat of war. There are still such people in the American churches, but all too few clergy or indeed politicians bring these indictments up to date. Worse, instead of calling out for repudiation of the unbridled capitalist interests that define, shape, color, and fill America’s public spaces, these religious leaders mostly welcome them, bowing down to the gods of secular culture, to trendy styles of commerce and entertainment, and to the market. Zealous hypocritical megapastors are not alone in having capitulated to Mammon, because after all their huge megacongregations love them for it—for the busy self-help centers and community social halls made over into feel-good pseudopsychotherapeutic rallying points for visiting politicians and snake-oil salesmen, for the churches’ transformation into power bases with their own revenue streams.

But while high-minded secular liberals denounce the bloated God shouters for their divisive anger, they don’t always themselves renounce our common submersion in the shallow waters of America’s money-soaked culture. Nor do they see that the small-minded, mega-ambitious scientists and neoatheists who attack all churches and deride all religions for their destructive irrationality, are also profiting from the inane superficialities and hypocrisies of “public opinion,” and that this is just as dangerous to the well-being of our republic.

When Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, and other neoatheists speak of “religion,” what do they think they’re talking about? Their critiques, varied as they may be, come nowhere near the wisdom or complexity of the Founders’ skepticism about ecclesiastical “trappings,” as Schleiermacher called them, and they disregard the deep wellsprings of human feeling that churches are supposed to channel, as Schleiermacher understood. Hope, fear, transcendent meaning, joy, suffering, terror, and love don’t seem to figure in their assessments. Well, it’s easy to demonstrate the mere irrationality of “belief in God” when you reduce the idea of spiritual life to fatuous, banal insignificance. (I might add that their one-dimensional, simplistic ideas about scientific inquiry also pervert the respectful, awe-filled language of true science and reason—but that’s another story.)

As the world careens along new highways of communication and trade, as manifest inequalities in the financial, economic, and labor markets increase, as toxic brews of racist and ethnic hostility simmer or boil over, you might hope for some depth and nuance. You might want to hear the voices of people, whether atheists or believers, representing the large majority of Americans who have welcomed modern science, cared about social justice, honored the life of the spirit, and tried to resolve, not intensify, the tensions between state, society, and church, to adjust, not destroy the ligaments connecting religion and modern science. But, like the pastors, too many of America’s political leaders seem undone—as much perhaps by their own complicity in the unforeseen victories of greed and aggression as by the callous disregard of the commonweal and the unleashing of local and international violence all over the globe. There are striking exceptions, of course, like the surprising victor in the 2008 presidential election, but public discourse in America continues to be rancorous and trifling, despite President Obama’s contrary example.

All the more reason for both good government and good religion to work for a renewal of the republic’s best, most benign energies. That would require secular, agnostic, and atheist voices, together with religious ones, to adjust their vocabulary and tone to the requirements of the public square. Our vulgar mass culture won’t encourage this, naturally, but why surrender ourselves to the lowest common denominator? Good governance never does. And were pastors, priests, and rabbis to step back a bit—back from what has become for some of them either chauvinistic drum beating or cynical poll counting or an anxious search for cultural “relevance”—and instead offer their flocks a separate place and time to reconsider, say, the imperishable, eternal spiritual values of humility, silence, and principled, practiced nonviolence, they would purify their own bloodied discourse, remove it from hectic public argument where it doesn’t belong, and offer a countervailing force to our media’s triviality and our society’s implausible loyalty to outmoded, only half-understood imperial grandeurs.

We should never forget—the Founders never forgot—that the most dangerous, most deluded ventures have been those animated by religious zeal, and zealous belief in the virtues of America’s secular way of life may count as one of these reckless imperial religions. American churches could teach us about this instead of demonstrating it, help us battle our moral and spiritual weaknesses—our hubris, vanity, and complacency—instead of indulging them. That task, like the task of governing our unruly, complicated nation, needs plenty of hard-headed, realistic political smarts, and it absolutely requires a level, courteous tone of voice. We must learn how to talk to one another.