To place oneself in the position of God is painful: being God is equivalent to being tortured. For being God means that one is in harmony with all that is, including the worst. The existence of the worst evils is unimaginable unless God willed them.

—Georges Bataille, 1957

Juan Everardo Nithard, Grand Inquisitor of Spain, by Alonso del Arco, 1624.

First published in tsarist Russia in 1880, The Brothers Karamazov is Fyodor Dostoevsky’s metaphysical masterpiece, a novel alive with rumors of damnation and intimations of immortality. Sigmund Freud believed that the book betrayed darkly enigmatic, even criminal tendencies in Dostoevsky, while a Russian neologism—Karamazovshchina—came to denote the depravity, violence, and psychological deviation which the work explores. Like much of Dostoevsky’s fiction, his final novel combines the tragic with the grotesque, moments of mystical ecstasy with episodes of savage farce. His characters seem to occupy a permanent state of pathological anguish or morbid sensitivity: ruined gentlefolk, buffoonish landowners, and socially paranoid clerks reap a perverse delight from being insulted or humiliated.

His extraordinary novels, among them Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1869), and Demons (1872), present a society that is sunk in feudal poverty but gripped by avant-garde ideas, awash with anarchism and nihilism, God-fearers and God-deniers. As one who felt the lure of Russian Orthodox Christianity, Dostoevsky set his face firmly against radical politics and liberal secularism; like many a modernist, he was as politically conservative as he was artistically audacious. Yet his imagination was haunted by rebels and parricides, by the damned and debauched, as much as by the saints and scripture. Perhaps dissoluteness is merely a crooked way to heaven. Perhaps the devil understands more about God in his own fashion than the stuff-shirted prig.

St. Francis preaching to the birds, from St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata, by Giotto di Bondone, c. 1295–1300. Louvre Museum, Paris, France.

The Brothers Karamazov is not only a meditation on grace and sinfulness, hell and salvation. It is also a whodunit. Enormously complex and running to nearly one thousand pages in some editions, the novel revolves around the murder of the landowner Fyodor Karamazov; and the whole action—packed into a mere four days—provides the highly wrought drama of the finest of detective stories. On this slim narrative foundation rests an enormous, unwieldy superstructure of social commentary, religious meditation, and philosophical rumination. Fyodor’s sons, the titular brothers, occasionally teeter on the brink of madness and spiritual ruin, each exhibiting contempt for petty-bourgeois morality. The violent and sexually dissolute Dmitri, a half-sensual, half-childlike moral ruffian, is rent by Oedipal rage. Alexei, the youngest brother, equally disdains the moral middle ground but in the direction of the angelic rather than the demonic. The rationalist middle brother, Ivan, appears to reject God out of hand, engaging in a lively debate with the Devil, who appears as a shabby-genteel figure wearing a pair of unfashionable checkered trousers.

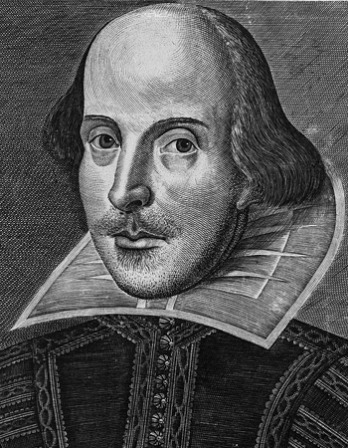

The most extraordinary set piece in the novel is “The Grand Inquisitor.” Ivan shares the tale of the Grand Inquisitor and Jesus with Alexei, as part of a continuing dialogue between the brothers on the question of religious faith. Their discussions are dramatic, strategic affairs rather than straightforward philosophical arguments. We are not therefore to mistake this marvelously rich narrative simply as a reflection of Dostoevsky’s own views. Like Marlowe’s narrative in Heart of Darkness, it is a story within a story. We do not know how accurately it reflects Ivan’s own beliefs, or how far it is influenced by its conversational occasion. During the episode, we are allowed no direct access to his consciousness. Instead, we are given a story which has no existence apart from this particular act of telling, which Ivan himself airily dismisses at one point as “just the muddled poem of a muddled student.” Perhaps he is just trying to get a rise out of his brother, who finds the fable more or less incomprehensible. Is he just out to shake Alexei’s faith? The complex, devious form of the episode, in other words, alerts us to the fact that we are in the presence of literature, not philosophy or theology. The Grand Inquisitor indicts Christ, which does not seem characteristic of the religiously inclined Dostoevsky. On the other hand, the Inquisitor’s low view of the common herd sounds close enough to his author’s own opinions. There is nothing in this great chapter we are allowed to take straight. The truth is not to be bought so cheaply.

“The Grand Inquisitor” is simple enough in plot: Jesus returns to earth, imprudent enough to choose as his point of reentry the city of Seville during the Spanish Inquisition. The near-ninety-year-old Grand Inquisitor orders his guards to seize the Savior, intent on having him burnt the next day in the public square as “the vilest of heretics,” and enters into Jesus’ prison cell to explain why. What follows is either one of the craftiest apologies for religious despotism ever written or a scathing satire of such autocracy. Why has Jesus, the Inquisitor demands, bound the intolerable burden of absolute freedom on poor, feeble, depraved humanity? How dare he and his Father profess their eternal love for men and women while dangling before their eyes impossible ideals? Better, surely, to offer people what they clamor for most—the bread of the earth—rather than some ethereal bread of heaven. The terrible truth is that human beings cannot bear the burden of freedom. “There is nothing more seductive for man than the freedom of his conscience,” the Inquisitor explains to Jesus, “but there is nothing more tormenting either. And so, instead of a firm foundation for appeasing human conscience once and for all, you chose everything that was unusual, enigmatic, and indefinite, you chose everything that was beyond men’s strength.” Man yearns for nothing more than to surrender his frightful liberty to some benign ruler, who will care for his bodily needs and relieve him of the spiritual suffering known as the will to choose.

The only relief, the Inquisitor suggests, is the Church. “Better that you enslave us, but feed us,” is the people’s cry; the Church in its wisdom responds to this plea with the three sacred consolations of “miracle, mystery, and authority.” Unlike the ruthlessly intellectual Ivan, the common people want to worship, not understand, and the Church’s traditional combination of miracle working, a cloak of mystery and enigma, and an authority which appeals to no purely rational foundation, graciously allows them veneration. The Grand Inquisitor understands, as he is sure God does not, just how weak and wretched human beings are. His love consists of protecting them in their frailty, not sadistically rubbing their noses in it. When the Grand Inquisitor ends his denunciation, Jesus says nothing. Instead, he leans forward and kisses the old man on the lips. The Inquisitor does not have Jesus put to death after all. Instead, he sends him away, demanding he never return.

Unlike most atheists and agnostics—in fact, unlike most devout believers—Dostoevsky grasps that God is the source of human freedom, not the obstacle to it. God’s love, as Thomas Aquinas argues, is what allows us to be ourselves, as the care of a wise parent allows us to flourish as autonomous beings. Paradoxically, it is our dependence on God which liberates us. Dostoevsky has no patience for the lurid adolescent fantasy of God as a Big Daddy who is out to spoil our secret pleasures, a kind of celestial bully or Bill O’Reilly in the sky. We have good psychological reasons for cherishing that fantasy, chronic masochists that we are. Freud knew well the gratification we reap from the pummeling that our merciless, vindictive superego doles out to us. It is just that we have to unlearn this infantile view of God and come to see him as friend, lover, fellow sufferer, and counsel for the defense. And this we are notably reluctant to do. It is far more convenient to view him as an irascible old bastard who, like some pampered rock star, needs to be endlessly placated and cajoled. That way we can enjoy the Oedipal delights of rebelling against him.

The Grand Inquisitor is also right to see that God is overwhelming, for in the Old Testament, Yahweh manifests as a fearsome fire who is terrible to look upon, a sublime abyss that defeats all representation. What the Inquisitor fails to grasp is that what is sublimely overwhelming about God is his love. He is a holy terror who destroys only in order to renew, uncompromising in his mercy and forgiveness. His passion for his creatures has the intransigence of all purely unconditional things. God does not have, as many Gnostics comfortably imagined, a creative face and a destructive one. The scandal is that the two faces are one and the same.

The Sacred Grove, by Arnold Böcklin, 1882. Kunsthalle Hamburg, Germany.

Freedom, too, has two faces. It is both gift and curse, poison and cure, self-achievement and self-undoing. The lives of free creatures are both precarious and exhilarating, which is more than can be said for goldfish. The historical animal, unlike the natural one, is perpetually at risk, “condemned to be free,” says Sartre. “We live in freedom by necessity,” Auden adds. We drag our liberty behind us like a ball and chain. But while human beings can abuse their freedom, they are not truly human without it. The greatest compliment ever paid to humanity is the doctrine of hell. If we are free to reject the very source of our freedom, spit in the face of our Creator, then we must be mighty indeed. And if the Creator has humbled himself in this way, willing his own vulnerability, then he is perhaps not as controlling as he is rumored to be. The thought, however, is as alarming as it is agreeable, which is why the Grand Inquisitor can see nothing better to do with freedom than to yield it up instantly to another, like a soccer player desperate to pass the ball he has just received.

This act of renunciation, we may note, is not quite the same as the belief that the highest form of freedom is the voluntary ceding of it. For the Inquisitor, who has the demeaning view of humanity typical of the conservative, men and women should abandon their liberty because it is a curse. By contrast, for a certain kind of tragic protagonist, freedom is to be surrendered precisely because it is our dearest possession. If we can freely give it away, grapple our destiny deliberately, then we are invulnerable indeed. In the very act of submitting to a higher authority, we reveal a power that transcends it. There is something of this paradox in the crucifixion of Christ, as Jesus’ loving acceptance of the Father’s will lays the ground for his resurrection. Only by embracing humiliation and death, without thinking of them as stepping stones to glory, is he able to transfigure weakness into power. Yet this paradox may also be the devil’s most subtle temptation. It was for those Nazis who found a deeper kind of freedom, one far superior to the paltry liberal variety, in submitting themselves to the Führer and Fatherland. There is a thin line between the SS commandant and the martyr who voluntarily gives up his or her body to be burnt for the sake of others.

Americans typically think of the positive aspects of idealism, whereas the Inquisitor attends to its destructive consequences. For a European like myself, the idealism of the United States, which is also, ironically, one of the most materialistic civilizations history has ever produced, is a constant source of wonderment. Americans must affirm rather than deny, hope rather than lament, be winners rather than losers, eternally aspire rather than cravenly submit. In this Faustian world of ceaseless striving, negativity constitutes a thought crime. With a victory of mind over matter worthy of Christian Science, there are no limits to the human will.

This blasphemous ideology, summarized in the common American lie that you can do anything you set your mind to, fails to acknowledge the frailty and finitude of the human, which is where the Inquisitor knows better. Also unlike the Inquisitor, this boundless optimism fails to acknowledge what one might call the terrorism of the ideal. Ideals are essential, but like the “law” for St. Paul, they can do no more than show you where you went wrong, but they cannot reveal to you how to go right. This is why Paul calls the law cursed. Ideals have the stiff-necked implacability of the Freudian superego, a faculty which encourages us to aspire beyond our powers, fail miserably, and then lapse into self-loathing. Idealism is the accomplice of violence and despair, not an antidote to them. The neoconservative desire to drag a barbaric world into the light of civilization is on display at Guantanamo Bay.

It is against this high-minded fury, this self-destructive cycle, that the Inquisitor seeks to protect the common people. If we do not expect too much of others, we will not fall into postures of tragic despondency when they inevitably fall short. Cynicism or nihilism is the other face of idealism. Realism is the only sure foundation for the moral life. What we share most with our fellow human beings is our fleshly weakness. Any solidarity based not on this, but on some community of noble purpose, is likely to prove fragile. Solidarity of weakness is mutual forgiveness, and forgiveness represents the ultimate form of realism since, in order to be authentic, it must reckon with the full horror of the offense in the act of setting it aside. As Freud was aware, man’s more sublime impulses must be rooted in his baser ones, and will not flourish otherwise. What we creatures have in common, in the end, is the unadorned body, which is what is most universal about us but also what is most vulnerably precarious and particular. This is why the concentration-camp victim, stripped of all specific culture and history, is prototypically human in his or her very dispossession. The real alternative to the idealist is the loser. The message of the New Testament is that it is above all the losers, whores, serial adulterers, colonial collaborators, and scum of the earth, not the pious and well-behaved, who will inherit the kingdom. It is notable that Jesus does not even ask these shady characters to repent before he consorts with them, a striking and scandalous innovation in Judaic practice.

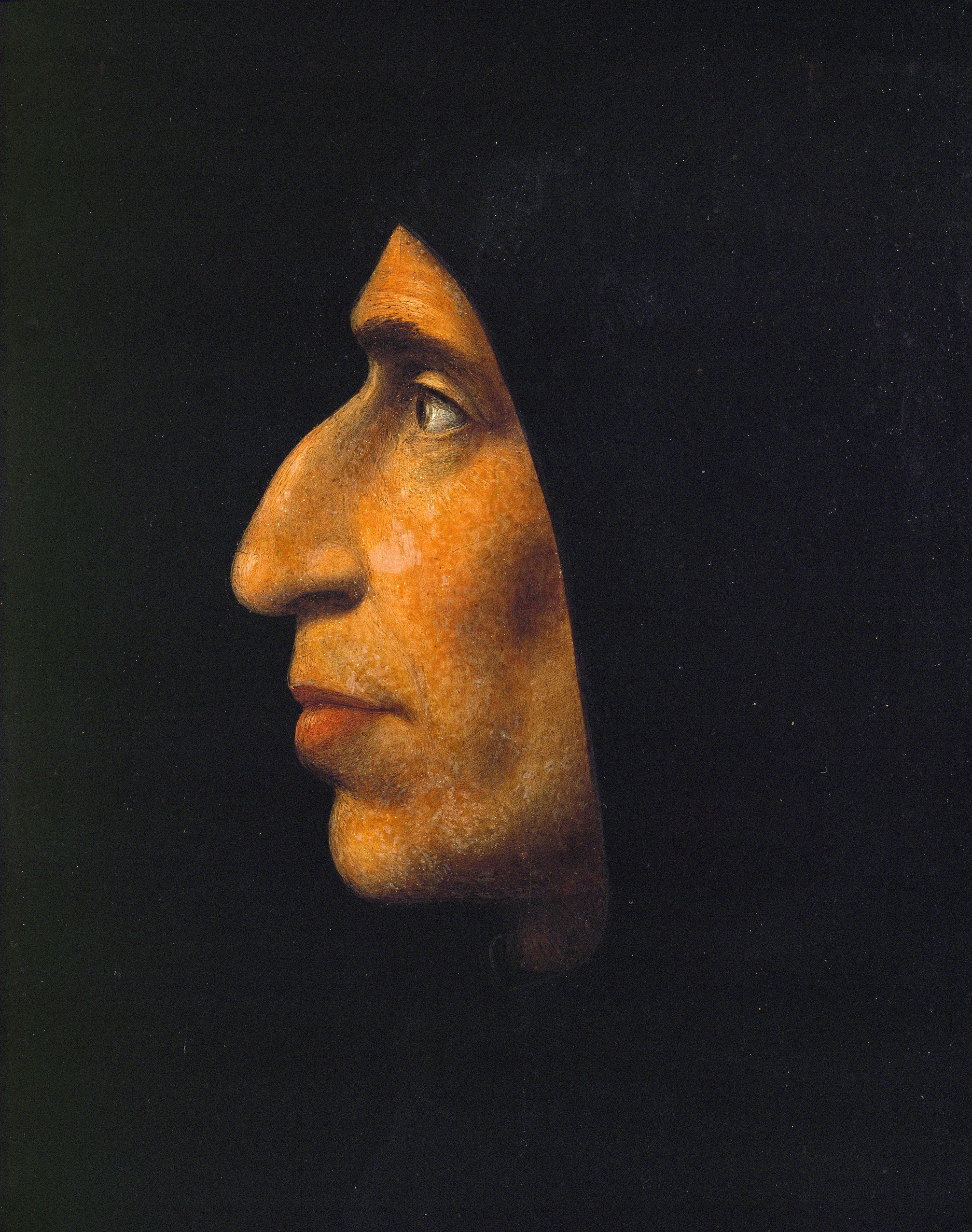

Girolamo Savonarola, by Fra Bartolomeo, c. 1495. Museo di San Marco, Florence, Italy.

The Grand Inquisitor’s theology goes awry because he does not see that the dangerous freedom God bequeaths to men and women is, among other things, freedom from the law. Which is why Jesus says, “My yoke is easy, and my burden is light.” It is the legalistic Scribes and Pharisees, so he claims, who bind intolerably heavy burdens on the backs of the poor. Jesus’ greatest demands on the other hand are love and mercy. With these simple requests, he shows that God is not Big Daddy, not a restrictive and withholding adversary. In the Old Testament, the Hebrew word for “adversary” is Satan, and God begins to look like Satan for those who conceive of him as a fearsome Mega Power, and who think that they can bargain their way into his favor by doing all the right things. According to Jesus, God has already forgiven them—what they need to do is let him love them. This is exceedingly hard. It is far more pleasurable to hug one’s chains.

The Grand Inquisitor ranks among those who regard God as their adversary. He believes that like a brutal despot, God loads on men and women more than they can bear; the burden he loads on them is known not as tithe or tax but freedom. However, this overlooks God’s own solidarity with human weakness, which is known as Jesus. On Calvary, God proves feeble and fleshly even unto death. His only signifier is the tortured body of one who spoke out for love and justice and was done to death by the state. Only if one can look on this terrible failure and still live can one lay a foundation for anything more edifying. Only by being entombed in the earth can one reach for the sky. It is in the place of excrement, as Yeats reminds us, that love has pitched his mansion. Any moral idealism that refuses this truth is just so much ideology.

Dostoevsky must have known that the Jesus of the New Testament rejects the Inquisitor’s own sharp distinction between earthly and heavenly bread. Salvation for Matthew’s gospel is not a “religious” or ethereal affair; it is a matter of feeding the hungry and visiting the sick. In true Judaic spirit, the teaching is ethical to core. It is the materialistically minded who like their religion to be otherworldly, in compensation for their own this-worldly crassness. It is not surprising that a material girl like Madonna should be attending classes on mysticism at the Kabbalah Center in Los Angeles. How else can she escape for a moment from her agents, minders, managers, hair stylists, and the rest? Surely salvation cannot lie in anything as prosaic as a cup of water and a crust of bread. The Grand Inquisitor is a thoroughly worldly type, objecting to what he sees as cruelly unrealistic spiritual demands. What he does not see is that God is a unique kind of superego, one who loves and accepts failure rather than simply rewarding success. Nothing could be more worldly wise than that.