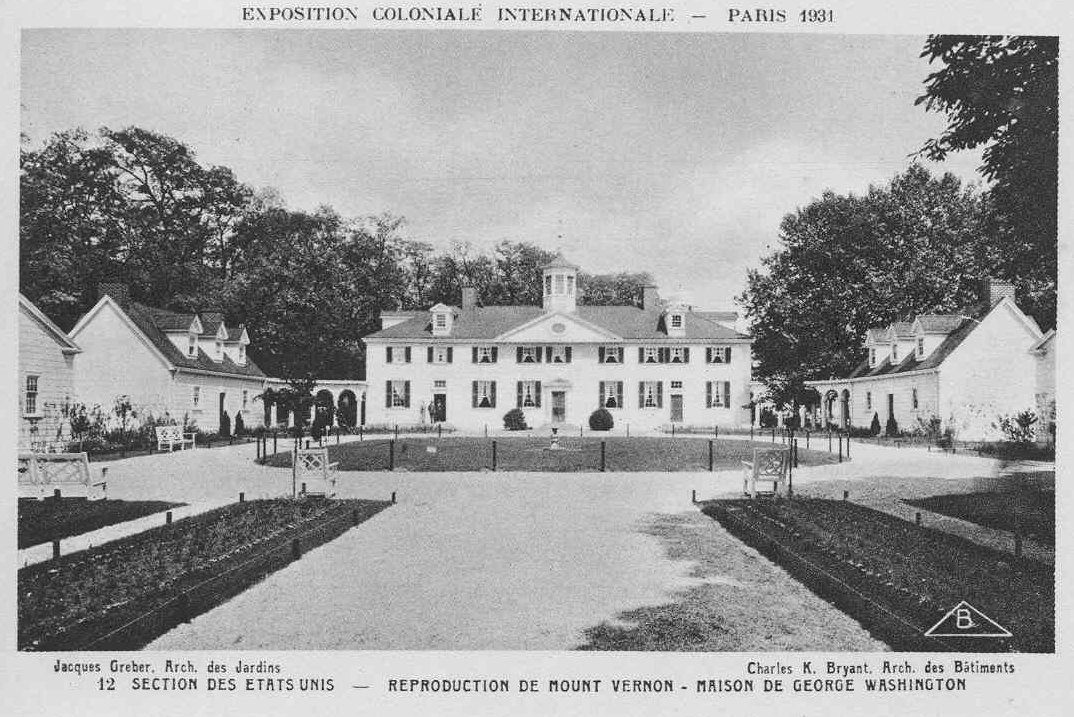

Replica of Mount Vernon in suburban Paris, constructed in 1931.

It was a coup de coeur, says screenwriter Catherine Tavernier, using a French phrase equivalent to “love at first sight.” In fact, its meaning is more visceral: a “blow to the heart.” She uses it to describe her first encounter with the house she lives in today, a wide, colonial-style mansion on one-and-a-half acres of well-groomed lawns.

The first time she saw it, driving past, she climbed the white fence along the roadside to get a look at the architecture up close, circling around to see the row of imposing pillars on the south-facing terrace. After doing research, she learned the house she had stumbled upon was in fact a perfect replica of George Washington’s Mount Vernon, built for the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition before arriving in its current location, across from a golf course in the well-to-do Paris suburb of Vaucresson.

Tavernier knew she had to move in.

In 1930 the United States hesitated over whether or not to participate in the celebration of Europe’s colonial empires. As the French organizers of the exposition would later archly note, America “attaches a somewhat different meaning to the words colonial possessions…If, for us, these words evoke the traditional idea of national expansion with the civilizing mission,” the United States “remains very reserved in affirming a colonial policy.”

Yet in the interwar years French officials placed great importance on a public display of unity between friendly nations and continued to lobby for a U.S. presence. The fair’s champion, the colorful French colonial hero, Marshal Hubert Lyautey, went before the American Club of Paris in early 1930. Quoted in a New York Times dispatch published the following day, Lyautey addressed his audience in terms that have not aged well: “Nobody can appreciate better the value and difficulties of aiding handicapped peoples than your president, Mr. Hoover, whose admirable organization and genius during the war”—he meant World War I—“saved hundreds of thousands of women and children from famine.”

Colonial expositions had branched off from so-called world expositions around the turn of the twentieth century. Though seen elsewhere in Europe, the colonial variation was especially popular in France. A half dozen cities around the country held their own expos, culminating in the 1931 extravaganza. Many were organized by local chambers of commerce hoping to encourage business between the metropole and France’s overseas possessions.

The 1931 organizers, particularly Marshal Lyautey, wanted their fair to emphasize the educational over the exotic, a “model city,” as historian Patricia Morton writes, that would educate French citizens about their far-flung colonial empire. It was, in other words, explicitly intended as colonial propaganda, designed to increase knowledge of and commitment to the colonies at a time when independence movements had emerged both abroad and at home. (In response, the Communist Party staged an anticolonial exposition called “the Truth About the Colonies” not far from the main event.)

Whether or not it was Lyautey’s flattery that did the trick—it’s possible the U.S. was ready to look outward after an isolationist period—by the summer Hoover and Congress had agreed to participate in the expo. Though in the depth of the Great Depression, they allocated $250,000 to the project.

Nevertheless, the centerpiece the American planners chose for the U.S. pavilion seems to hint at a continued ambivalence about participating in a paean to European colonialism: a to-scale replica of Mount Vernon, home of the father of American independence.

Architectural replicas appeared throughout the 1931 Colonial Exposition, which promised visitors “a tour of the world in a day.” In “bringing Mount Vernon to Paris, the intention was in part to bring America to people who would never go to America,” says historian Lydia Mattice Brandt, author of the recently published book First in the Homes of His Countrymen: George Washington’s Mount Vernon in the American Imagination. “But part of it too was that, by the 1930s, this practice of replicating historic or iconic national buildings at world’s fairs was so ingrained,” she explains. Replicas, or more often some pastiche of regional features, made for simple and effective branding.

Mount Vernon, already as iconic in Europe as in America, appeared in six expositions between the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the year 1934. The house represented America abroad and, in the U.S., the archetypal style of the Colonial period. The 1930s—specifically the years around the 1932 bicentennial of George Washington’s birth—proved to be the apex of the Mount Vernon craze, according to Brandt. The Paris fairground replica would be the first of three in four years.

The fair’s lofty goals notwithstanding, promoters also had to put on a spectacle that would draw a crowd. In the era before mass travel, that often meant transplanting buildings and scenes from faraway places. Colonial expositions and traveling shows often featured “native” craftsmen or staged family scenes, sometimes separated from bystanders by some sort of fence.

The centerpiece of the 1931 fairgrounds on the eastern edge of Paris was an approximate reproduction of Angkor Wat, an enormous Khmer temple in French Indochina. The red-walled palace showcasing Afrique-Occidentale française (French West Africa) had a central 150-foot tower, all loosely based on regional styles and construction methods.

Sandwiched between the colonial empires of Portugal and Holland was the house the New York Times dubbed “Mount Vernon on the Seine.” The Times reported that it would “occupy a sloping plot on Lake Daumesnil, in the wooded park at Vincennes with the River Seine in the distance. With the outlook over these waters the setting will be not unlike that of Mount Vernon overlooking the Potomac.”

Sears Roebuck had custom-produced the new Mount Vernon at a 10 percent markup, less than the usual profit margin for mail-order homes. Each piece was labeled with a number, similar to the technique used for the steel frames of American skyscrapers, and sent by ship from Newark. On-site construction took just two weeks.

“It was an image of American productivity and efficiency in economic terms that I think cannot be divorced from the Depression,” says Brandt. Extensively planned and publicized back home, “it was a really hopeful image,” intended to communicate to Americans and Europeans “that the U.S. was going to make it through the Depression,” and do so based on the “same values and aesthetics it had since George Washington’s time.”

This demonstration of America’s modern manufacturing prowess seems to have been somewhat lost on the French. They found the white mansion with its clean lines modest next to their elaborate pavilions but nonetheless charming. Yet its restraint, Brandt says, also resonated with Americans, who would not have appreciated great opulence amid Depression-era hardship.

The French paper L’Instransigeant described it as a “modest, country house,” allotting more lines to an admiring catalog of the objects on display inside: relics of America’s founding fathers and France’s participation in the U.S. struggle for independence.

In the entryway, visitors could see a cane owned by Benjamin Franklin—who had spent almost a decade in Paris, arriving as the first U.S. ambassador to France in 1776—and a sword that had belonged to Washington himself. Manufacturers in Michigan had crafted furniture roughly modeled on the originals in Virginia. The room where General Lafayette had stayed when he visited two decades after the war was perfectly duplicated, as was the bronze key to the Bastille he had presented to Washington. Visitors could see a painted version of the rug Washington received from King Louis XVI and could read the 1778 letter the king wrote to America’s young government. A guidebook to the exposition promised the presence of Washington’s grand-niece in the music room, playing songs and operas on the harpsichord. Expositions in this era attracted visitors by holding special events. On July 4, during “American week,” a pageant with French actors reenacted Lafayette’s reception in 1793, complete with the dancing of minuets and the drinking of mint juleps.

However, the U.S. did also present its current overseas possessions at the fair. One wing of Mount Vernon housed an exhibition on the Panama Canal and another on “the Klondike” (Alaska). Outbuildings featured Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Hawaii, and Samoa. A postcard sent from the exposition depicts a Hawaiian-themed restaurant, with thatched table umbrellas and kiosks, the smaller of the two selling waffles. A group of men standing in a corner nearby wear Revolutionary-era dress—long coats and stockings and large hats.

Some 8 million people walked the grounds of the 1931 Exposition between May and November. Yet ordinary visitors left frustratingly few accounts of their impressions—with the exception of postcards, which you can find in the archives and flea markets of Paris and for sale by the hundreds on eBay. Most messages are simple and short.

“Bonjour from the exposition,” wrote one visitor on the reverse of a photo of Mount Vernon taken before the exposition, when the grounds were still empty. The postcard was dispatched to central France.

“Most beautiful—most popular,” another reports on the house in English. “It will be removed to the Chicago 1932.”

Mount Vernon would not in fact move to Chicago or New York; instead the expositions in those cities in 1934 and 1932, respectively, erected replicas of their own. A doctor from New York purchased the Paris structure as a home for his daughter and French son-in-law, reinstalling it in the suburbs at the opposite end of the city.

Brandt claims that the French replica changed the American landscape. While wealthy Americans had ordered replicas of Mount Vernon from prominent architects for their personal residences since the 1890s, Sears Roebuck included a modified version in its mail-order catalog the year after the exposition, making living in a version of Mount Vernon accessible to Americans nationwide. It offered the model again in 1933 and 1937, and other companies followed suit, popularizing the style around the country. Even small two- and three-bedroom houses could get a Mount Vernon–style veranda tacked on, according to Brandt.

The 1931 replica outside Paris would subsequently pass into the hands of French businessman Marcel Dassault. Born Marcel Bloch, Dassault got his start in aviation designing propellers used in World War I fighter planes and had become a successful airplane manufacturer by World War II, when he was stripped of his business and interned in Buchenwald before fighting ended. After the liberation of Europe, he returned to aviation, moving the headquarters of his company to the next town over from Mount Vernon in 1959. He purchased the house for entertaining.

In later years, the home was partitioned into offices, and then it sat empty for roughly a decade before Tavernier climbed over the fence. “I had the impression that I was arriving at Tara,” says Tavernier, referring to the plantation house in Gone with the Wind. In the years after she moved in, when her children were still small, “I felt like I was Scarlett having a Sunday tea.”

Mount Vernon is for sale again, for the sort of asking price that’s available only upon request.

This quintessentially American building is now a French historic landmark; its facade cannot be altered. Tavernier was still able to put in a year’s worth of renovations to the interior after she bought the house. So while it has the period elements—wooden moldings and decorative door frames and fireplaces—the first floor went from over a dozen rooms down to four, including a massive kitchen with floating islands and a living room full of sleek, pale furniture—including a shiny white piano.

Washington’s office off the entry hall has become a small TV room. In a nod to the past, the mounted head of a mouflon, a wild sheep with long, curling horns, hangs above the couch. Though the grounds have shrunk, the colonnaded patio still looks out onto a wide, grassy lawn.

As the last of Tavernier’s children leave home, the soon-to-be empty nester wants to leave her white mansion either for Paris or the U.S. “I feel very tied to the United States,” she says, “even more so since living here.”

Explore Home, the Winter 2017 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.