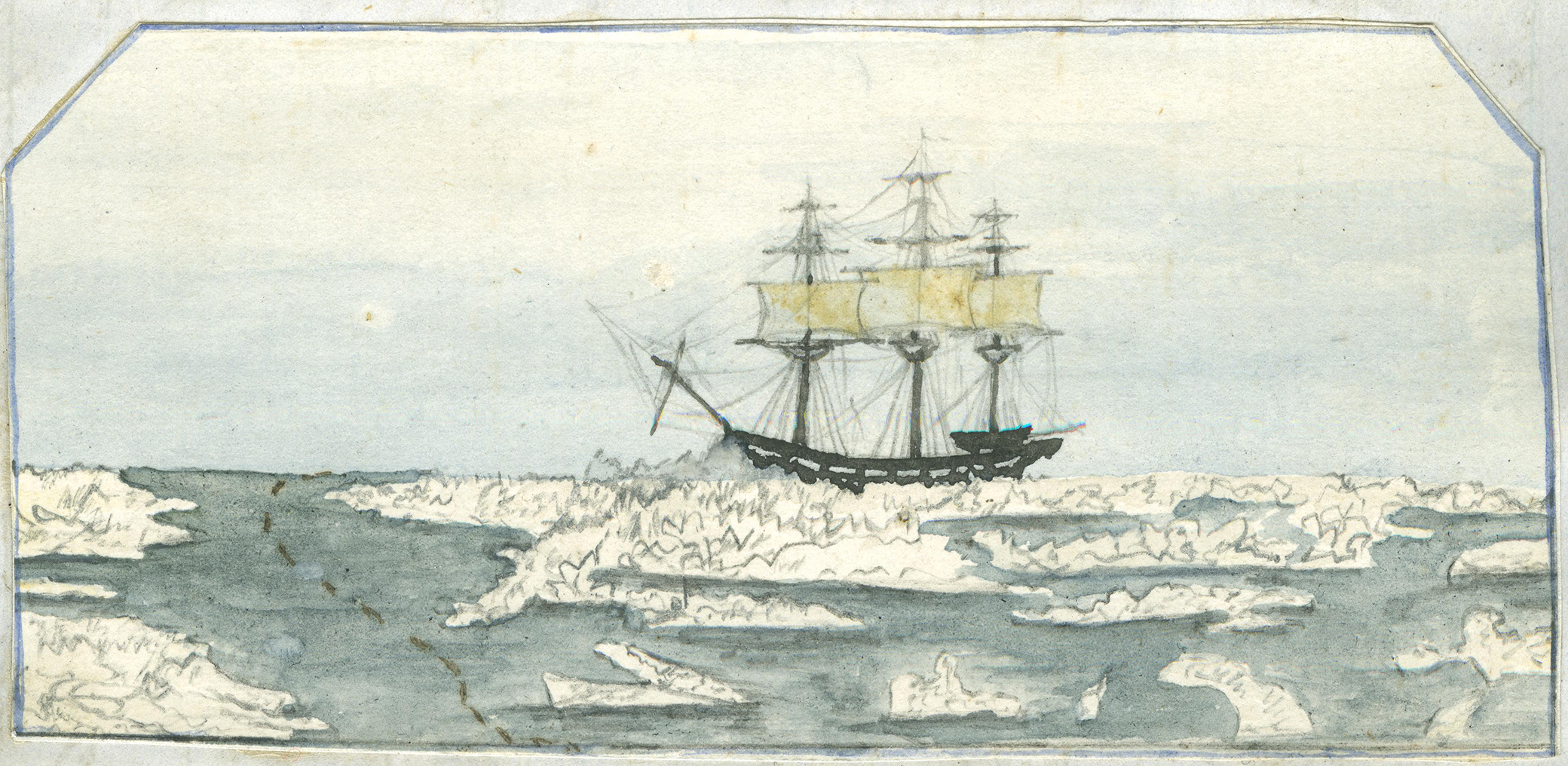

Boat on ice, from the Log of Samuel Smith, Surgeon to the Hon. Hudson’s Bay Co. Ship Prince Arthur from London to Moose Fort, June 13 to August 24, 1857. Flickr, Toronto Public Library (CC BY-SA 2.0).

In June 1578, the English privateer Martin Frobisher launched the last of three doomed voyages in search of a Northwest Passage to Asia. His fleet of ships left Plymouth one month later than planned, headed for eastern Greenland. Weeks into the trip, Frobisher’s fleet encountered a colossal storm of fog, snow, and ice. The expedition’s chronicler, a sailor named Thomas Ellis, described what happened next: “The storm increased, the ice enclosed us…so we could see neither land, nor Sea…the rigorousness of the tempest was such and the force of the ice so great that [the ice] raced the sides of the shippes…thus continued we all that dismall and lamentable night plunged in this perplexitie, looking for instant death.”

One of the ships sunk, and at least two others were put so far off course that they ended up backtracking by weeks. Three vessels were eventually able to make landfall near Baffin Island. They succeeded in filling their holds with 1,350 tons of a mysterious ore that Frobisher had discovered on a previous voyage, and which he believed to be gold. Setting off for England, more storms set in, with twenty sailors lost. When at last the haul of Frobisher’s ore was unloaded back in Bristol that August, it was melted down in Dartford, and the result, as one investor put it, “wrought far from the riches looked for.” The stuff, it turned out, was pyrite—fool’s gold—and entirely worthless. It was eventually dispatched as brickwork, still visible today in walls around Portsmouth and southern Ireland.

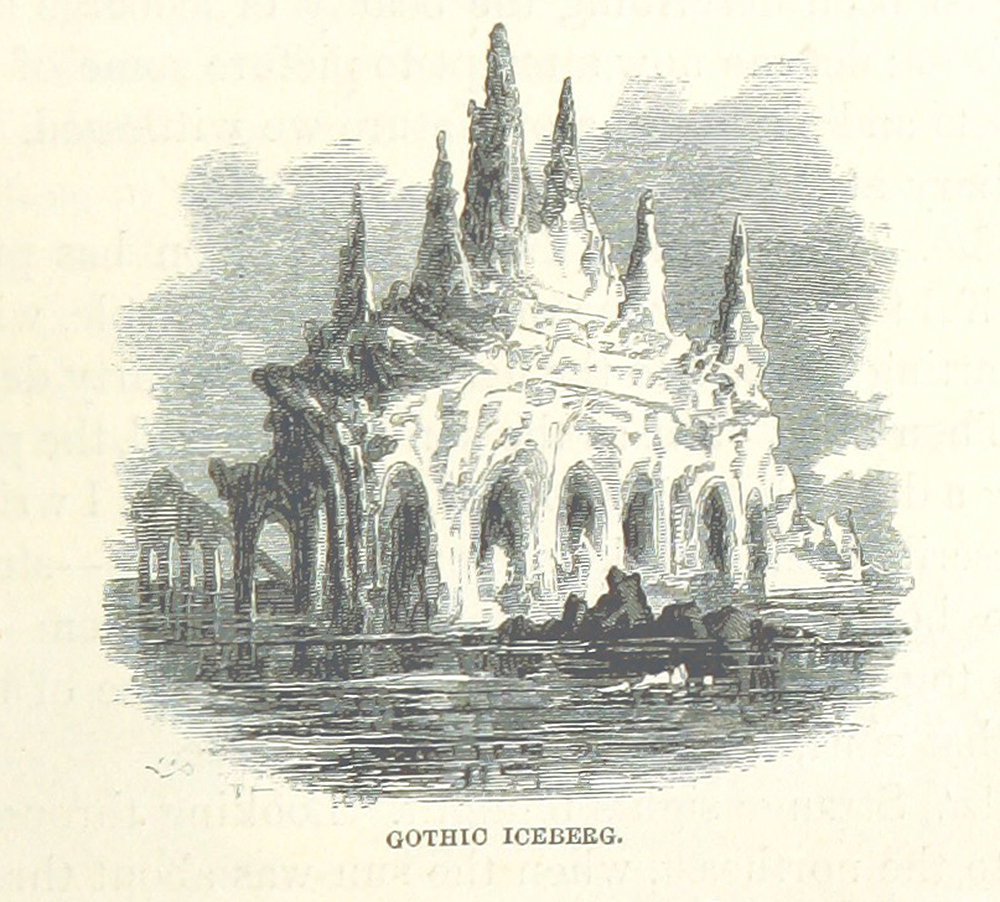

But after the ships drifted home, a remarkable little booklet was published to document (and partially defray the costs of) the disastrous voyage. Appearing in late 1578, it contained, among other things, the world’s first visual description of an iceberg. Made, supposedly, after drawings by Ellis himself, the print combined four separate views of an ice mass from a distance. Ellis apologized that the iceberg could not be “shewn” as a totality but could be envisioned only from various angles. As he wrote:

1. At the first sight of this great and monstrous peece of yce, it appeared in this shape.

2. In coming neare unto it, it shewed after this shape.

3. Approaching right against it, it opened in shape like unto this, shewing hollow within.

4. In departing from it, it appeared in this shape.

Muddled visual relationships between water and air, “land and Sea,” became, in Ellis’ ink lines, proffered as a sequence of views on a revolving, ever-changing hulk. Allegorized here was not just Ellis’ “perplexitie,” but also a confrontation with conditions that simply did not fit into European schemes of pictorial composition, space, selfhood, and communication.

Icy, unpopulated, commodity-poor, visually and temporally “abstract,” the far North—a different kind of terra incognita for the Renaissance imagination than the sun-drenched Indies—offered no clear stuff to be seen, mapped, or plundered. With this, the Arctic quietly yet powerfully challenged older understandings of image making in the early modern period. Not a continent, or an ocean, or a meteorological circumstance, the Arctic forced explorers, writers, and early artists from England, the Netherlands, and Germany to grapple with a different kind of “wonder.” Here, there were virtually no exotic animals, teeming forests, or enchanting civilizations to study or to loot. In the frigid North, the idea of description as a kind of accumulative endeavor of “representation” was thrown into question. The North was unsettling not because of dazzling difference, but because of monotonous sameness. Rather than an Eden, to Renaissance travelers the Arctic was something like the moon.

The Arctic was (and is) a physically dark and blindingly bright place; early visitors commonly described how it demotivated normal means of sight, of recognition. In 1579, an anonymous English pamphleteer spoke of a “penetrating cold that, boring out the inhabitants eyes, giues them the sauce of hunger.” Or as a Danish sailor simply said of Greenland in 1607: “We could never see.”

The Far North of America was not settled in the early years of European expansion the way the South was, and northern Asia was all but unknown to the West. Travelers’ accounts almost uniformly thematized blindness, obstruction, and disorientation: “We could not scarce see one another…nor open our eyes,” wrote one Arctic sailor in 1578. This was a poetics that (at least in later English cases) paralleled Elizabethan arts and letters. (We know that Shakespeare read descriptions of Siberia and the Scandinavian Arctic and lifted parts of them for Twelfth Night and Hamlet.) But being like nothing else, the Arctic regions confounded literary strategies of analogy. The ability to contrast and compare had been employed in more southerly voyages and other pilgrimages, of course. It was a move found in works such as Oviedo’s Historia general de las Indias (compiled in Mexico in the 1530s) or Hans van Staden’s Warhaftige Historia (1557) about Brazil. Yet in the polar narratives, it was singularity and inaccess that became a trope: “Walls, mountains, and bulwarkes of yse, choaked uppe the passage, and denied us entrance,” wrote Frobisher’s lieutenant George Best of Hudson Bay in 1578. For both the straits and their recounting, there was simply, as Best put it, “no waye to passe further in.”

For a few visitors to the actual Arctic, a common point of comparison was the desert. It was a terrain “vast and void,” as one explorer wrote, fraught with biblical overtones of barrenness, confusion, and itinerancy. Certain pamphleteers, for their part, traded on Northern dullness; “there is nothing but stuck-fish, whetstones, and cods-heads,” wrote one wit about Iceland; “it seemed to be the true pattern of desolation,” complained another. Or as Stephen Parmenius, a Hungarian poet who sailed to Newfoundland (and drowned there) in 1583, rhetorically posed in a letter, “What shall I say…when I see nothing but solitude?” (Of course in the Spanish West, barrenness could also be a topography: “There are very few people, the land is sterile, and the roads are wretched,” wrote a Spanish friar in New Mexico around 1517.)

And yet, being like nothing else, the Arctic was particularly vexing. Figural description of the region turned away from lists of things seen; recounting, indeed, the specifics of the Atlantic crossing itself or narrating, remarkably, voyagers’ internal wrestling with the removal of normal means of recognition, of sight. One account of a 1580 English voyage through the Asian Arctic described one sailor’s frustration at being unable to distinguish ocean from land. Another sailor off Greenland related an episode wherein his crewmates mistook frozen water for earth. Thinking they had hit solid terrain, they “sent our pinnesse [a small boat] off to discover it…but we were informed that it was only ice.”

This sensory confusion affected communication: Edward Hayes, who narrated Humphrey Gilbert’s voyage to Newfoundland in 1583, described how his crewmen “were incombred with much fogge and mists in manner palpable, in which we could not keepe so well together, but were disservered.” Then there is John Davis, sailor on one Frobisher voyage, daunted by “a strange quantity of ice, in one intyre masse, so bigge, as that we know not the limits thereof…incredible to be reported in truth as it was, and therefore I omit to speake any further of.”

Often, this was a confusion posed for rhetorical effect. And in the North, literary silence was often matched by the landscapes’ endemic blanks. This bred responses that could turn quietly self-reflective. Best apologized that, in his account “of me there is nothing else to be lo[o]ked for.” More than a defense of plain style, such phrasing summoned, on the one hand, a set of anxieties about sensory experience and, on the other, an ambivalence about how visual information—vital for the description of New World phenomena—could be transmitted for terrain that largely disavowed an aesthetic of precision, or could be reconciled with a faith that often disavowed the reliability of optical sight alone.

One of the strangest episodes from Frobisher’s last Arctic landing in 1578 involved the construction, on Baffin Island, of a house “of lyme and stone” that sailors filled with trifles and then abandoned: “We left therein dyvers of oure countrie toyes, as belles, and knives…Also pictures of men & women in lead, men on horsebacke, lookinglasses, whistles, and pipes.” It seemed a little Arctic Wunderkammer, proffering items to be taken away. The crew even left bread baking in the oven. Why? To some extent the house continued the trend of bartering with locals that the sailors had maintained over three voyages. As a triumphant proclamation of European technological superiority, the selection of the objects most astonishing might be the prints, drawings, or badges (“picture…in lead”) and the “lookinglasses.” As Sophie Lemercier-Goddard has argued, the latter were likely convex glass mirrors, cheaply imported to England as early as the fourteenth century. These shifted both shape and, importantly, size, depending upon the beholder’s place before them. Leaving such a mirror behind, along with replicated images fashioned by “European” artisanship, amounted to a kind of secular offering to the New World. As much as a colonialist overture, the little house was the first semipermanent architecture the English ever built in North America—meant to seed a colony that never happened, at least not on Baffin Island. The abandoned mirror, instrument of empire and trade, instead was left to reflect and, more accurately, refract the ever-shifting nothingness around it.

Excerpt adapted from Into the White: The Renaissance Arctic and the End of Image by Christopher P. Heuer. Used with permission of the publisher, Zone Books. Copyright © 2019 by Christopher P. Heuer.