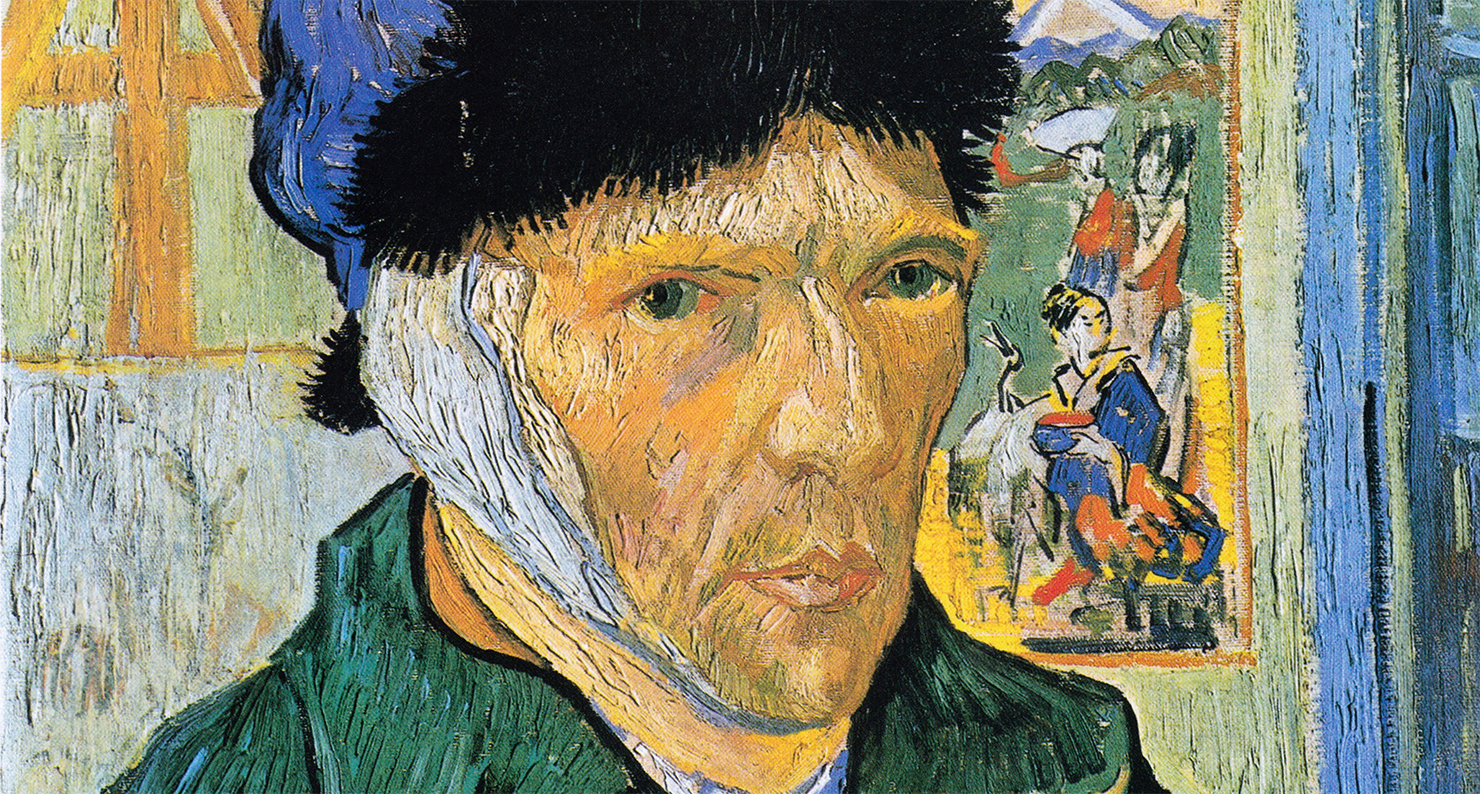

Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear, by Vincent van Gogh, 1889. Courtauld Institute of Art, London.

Van Gogh’s The Night Café is an image of destitution, its garish colors unable to hide its bleak desperation. Around the edges of the room huddle silent patrons, beneath the dandelion-halos of a few harsh overhead lights. The painting’s perspective is skewed: A billiards table juts out at an improbable angle, and the floor tilts forward as if the whole room is ready to spill onto the ground at the viewer’s feet. It’s an unsettling image, a distorted view through diseased eyes, vertiginous and bleak. “I have tried to express the idea that the café is a place where one can ruin oneself, go mad or commit a crime,” Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo. “So I have tried to express, as it were, the powers of darkness in a low public house, by soft Louis XV green and malachite, contrasting with yellow-green and harsh blue-greens, and all this in an atmosphere like a devil’s furnace, of pale sulphur. And all with an appearance of Japanese gaiety, and the good nature of Tartarin.” Van Gogh sought to unearth the darkness in something as banal as an all-night bar to show us what’s hiding underneath.

A month after Van Gogh finished The Night Café, Paul Gauguin arrived in Arles, invited by the younger painter to form something like an artist’s colony in a small yellow house where Van Gogh had been living. Gauguin arrived at night, waiting until daybreak at the same all-night café, that place of infernal solitude. Things did not go well; within a few weeks, their relationship had begun to sour. “Gauguin,” Van Gogh wrote to his brother, “does not like the little yellow cottage.” They quarreled about art, and about money. (“One thing that made him angry was having to acknowledge that I was very intelligent,” Gauguin later wrote with characteristic humility.) Even as they painted each other’s portraits and encouraged each other’s work, Van Gogh’s behavior became increasingly erratic, and a few times Gauguin awoke in the dead of night to find Van Gogh standing directly over his bed, silently staring at him.

Just after the winter solstice, on one of the darkest nights of the year, Van Gogh ended an argument by flinging a glass of absinthe at Gauguin’s face, and the latter resolved to leave Arles for good. The next night—December 23—Gauguin was walking home when, as he later recalled, “I heard a well-known little step behind me, quick and jerky. I turned around just as Vincent rushed at me with an open razor in his hand.” Van Gogh halted abruptly, and in that bleak alleyway the two men stared at each other for a long, perhaps interminable, moment. “The look in my eyes at that moment must have been very powerful,” Gauguin wrote, “for he stopped, lowered his head and ran back toward the house.”

Van Gogh took Luke the Evangelist as his patron because Luke is the saint of painters. But the saint whom I most associate with this artist, and particularly with that dead winter night in Arles, is not Luke but Lucy, patron of the darkest nights of the year. Lucy’s story began as a sort of sequel to that of another saint—as a young girl she’d come to pray at Agatha’s shrine, bringing along her mother, hoping to cure her dysentery. Agatha not only cured Lucy’s mother but also appeared to the young girl in a vision, telling her that she, too, would one day be revered in her home of Syracuse as Agatha was in Catania. Lucy, like Agatha, subsequently pledged her virginity and paid a similarly high price for it—she, too, was sent to a brothel at one point and later tortured. And, like Agatha, she’s now recognized by the body part cut from her during these tortures: her eyes.

At least, that’s the most common version of Lucy’s story; there are differing accounts of how she lost her eyes. Another involves a suitor who relentlessly pursued the virginal Lucy, repeatedly complimenting her on the beauty of her eyes. Lucy, wanting to be left in peace, simply gouged out her eyes and sent them to the suitor, telling him he was free to have them if he felt they were so beautiful and asking to be finally left in peace.

This story is likely apocryphal, but it has echoes of another, a story that also happened on December 23, 1888. After threatening Gauguin with a straight razor, Van Gogh took that same razor to a nearby brothel, where he cut off a portion of his right earlobe, giving it to a prostitute named Rachel and asking her to hold it for safekeeping.

It was these dual stories of self-mutilation that initially led me to equate Van Gogh and Lucy, but there are other reasons why I think he should have adopted her over Luke. “The symbol of St. Luke, the patron saint of painters, is, as you know, an ox,” Van Gogh wrote to Émile Bernard in the summer of 1888. “So you just be patient as an ox if you want to work in the artistic field.” But Van Gogh didn’t need a patron saint of patience; he needed a saint of the night, when he was most troubled. (“The thing I dread most is insomnia,” he wrote to his brother after he’d been hospitalized.) He needed a saint to offer hope in the darkness, salvation from the darkness of winter.

Lucy’s time is the winter, when the nights are long and unforgiving. Midwinter is sometimes called the “days of roughness,” precisely because it was impossible for earlier cultures to identify that exact moment when the earth begins its tilt back. Lucy, patron saint of blindness and of the darkest nights of the year, is meant to be celebrated on the solstice itself, but pinpointing the exact moment of the solstice has never been easy. Her feast day was originally on December 16, though it later changed to December 13. Neither of these is close to the solstice as we now understand it, but prior to the Gregorian calendar, the date of the solstice changed every hundred years. The Julian calendar was based on a calculation of 365.25 days to a year, when in fact the number is closer to 365.2422, creating a slight slippage that had added up to thirteen full days before Pope Gregory XIII rectified it in 1582.

Lucy’s day was still December 16 when Dante wrote his epic in the early 1300s, though the solstice then would have fallen on December 12. When John Donne took Lucy as his muse three hundred years later, the longest night of the year was December 9. But Donne’s great poem to Lucy, “A Nocturnal upon Saint Lucy’s Day, Being the Shortest Day,” is dated December 7. Donne didn’t know when the solstice occurred, nor when Lucy’s actual feast day was, but he understood on some level that Lucy’s is a movable feast—her day is every night, since at night all calendars stop.

Study me then, you who shall lovers be

At the next world, that is, at the next spring;

For I am every dead thing,

In whom Love wrought new alchemy.

Donne was far less sanguine than Dante that the world is perfectly ordered and just. He had been born Catholic in a newly Protestant country, which was being torn apart by religion and by conflicting views of the order of the world. His brother Henry was imprisoned in 1593 for harboring a Catholic priest and died of disease in prison (the priest, meanwhile, had been hanged until he was nearly dead, at which point he was disemboweled). Donne had learned to keep his faith a secret throughout his early years before ultimately converting to the Anglican faith in 1627.

It was three years later, with the deaths of both his patron, Countess Lucy of Bedford, and his young daughter Lucy, that Donne turned to the Catholic saint of darkness. Like Dante, he came to Lucy in his darkest hour, beset by gloom. But unlike the Italian, Donne could not find solace in a divinely revealed master plan of the universe. Dante found a love beyond death through Lucy’s intercession, but Donne saw death hidden even in love, despair that outweighed belief, darkness to match the longest night of the year. The bleakness of Donne’s work dispels the order in Dante. If the Italian found paradise emerging from the inferno, Donne found midnight in a summer’s kiss. “I am re-begot,” he tells us, “Of absence, darkness, death—things which are not.” Donne called on Lucy in the wake of a personal loss, and his poem suggests that if God exists, His purpose is only to affirm our emptiness. Lucy’s name is here invoked to remind Donne that the world will yet turn back on its axis, even if Donne himself can’t yet see it.

This is an excerpt from Colin Dickey's upcoming book Afterlives of the Saints: Stories from the Ends of Faith, which was published by Unbridled in June of 2012.