Street, Tangier, by John Singer Sargent, 1895. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950.

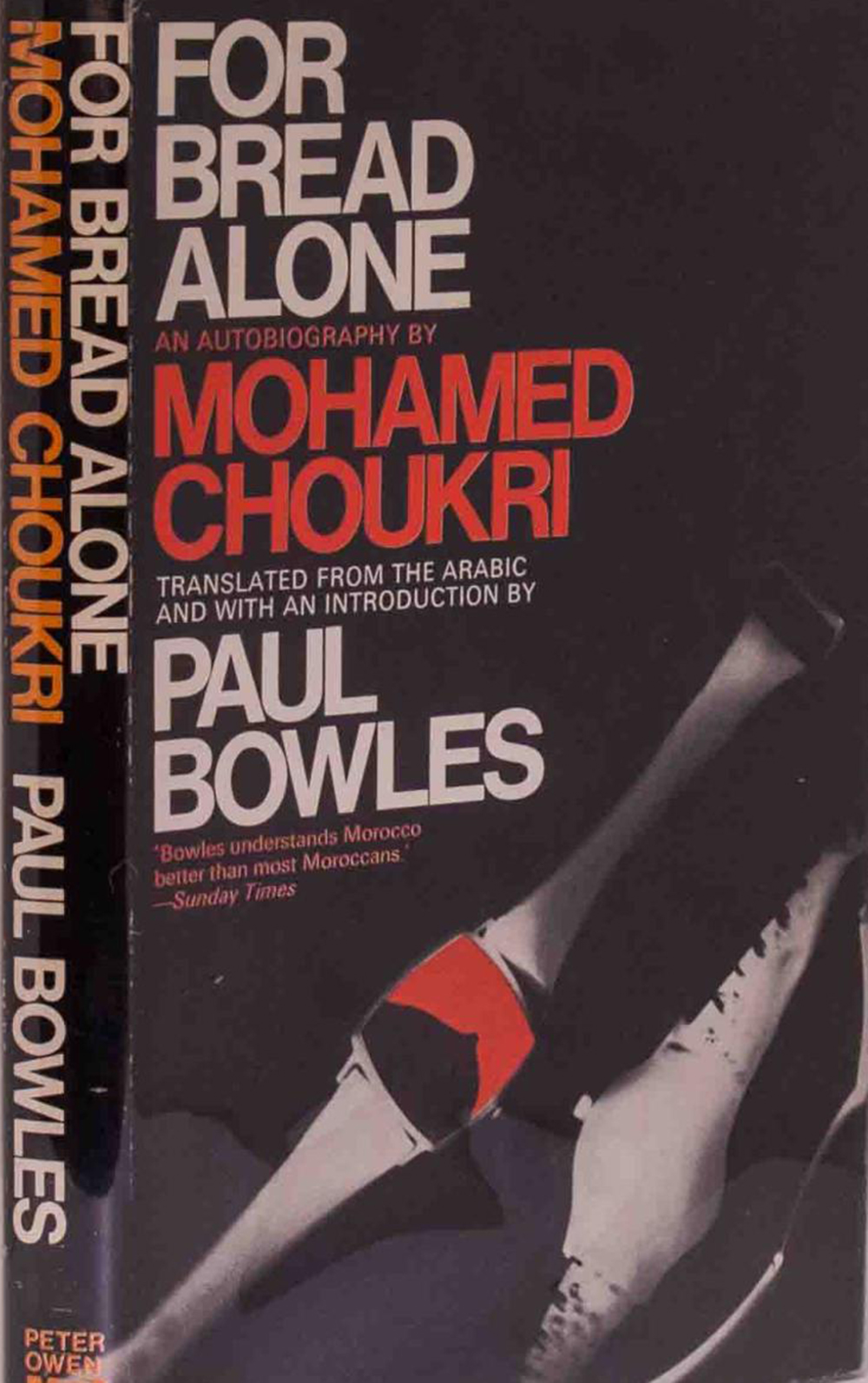

Mohamed Choukri, born in the Rif in northern Morocco, is one of his country’s most canonically important writers. His autobiography For Bread Alone remains a valuable and influential portrait of severe poverty in mid-twentieth-century Tangier. First published in 1973 in an English translation by the American writer Paul Bowles, the memoir is controversial for its frank portrayal of domestic violence, sex, and drug use. It was published in French in 1980, and in Arabic in 1982, but was banned from being published within Morocco until 2000.

But Choukri continued to write: short stories, a second memoir, and notes and journal entries about the many American and European writers who passed through his city. The last were collected in his books about Jean Genet, Tennessee Williams, and his translator Bowles, published in one volume in English in 2008 as In Tangier. Choukri is not as well-known in the U.S. today as the writers he profiled, but his writing about the expatriate literary scene in Tangier is honest and his perspective elucidating.

“Paul Bowles loves Morocco, but does not really like Moroccans,” Choukri writes of the man who translated his memoir for the English-speaking world outside his home.

About this, there can be no doubt…He assumed that after independence, they would return to their traditional way of life. But he was taken aback by their rejection of it in their attempt to become more and more Europeanized. The Morocco that Bowles loved will never return; with the establishment of independence, it was over.

The 1955 novel The Spider’s House was Bowles’ effort to understand Moroccans, Choukri believed. Its two protagonists, an American writer and a Moroccan teenager, navigate Fez as the movement for independence develops and an armed resistance carries out attacks within the city. The dialogue is peppered with the occasional Arabic word or transliterated accent in French. The teenager Amar is excited by the prospect of revolution but can think of it only in terms of ancient Islamic conquest:

For a moment, like a true Muslim, he contemplated the beauties of military discipline. There could be nothing, he reflected, to equal a government which was simply the honest enforcement, by means of the sword, of the laws of Islam. Perhaps the Istiqlal, if it were successful, could bring back that glorious era.

When Amar meets the leader of the Istiqlal party for independence, he is disappointed to learn that he is not a devout Muslim. As he imagines driving the French out of Fez, men on horseback with glinting swords come to mind. Bowles’ Moroccan protagonist is nostalgic and naive. In his 1981 Paris Review interview, he said,

Right away when I got here I said to myself, “Ah, this is the way people used to be, the way my own ancestors were thousands of years ago. The Natural Man. Basic humanity. Let’s see how they are.” It all seemed quite natural to me. They haven’t evolved in the same way, so far, as we have and I wasn’t surprised to find that there were whole sections missing in their “psyche” if you like.

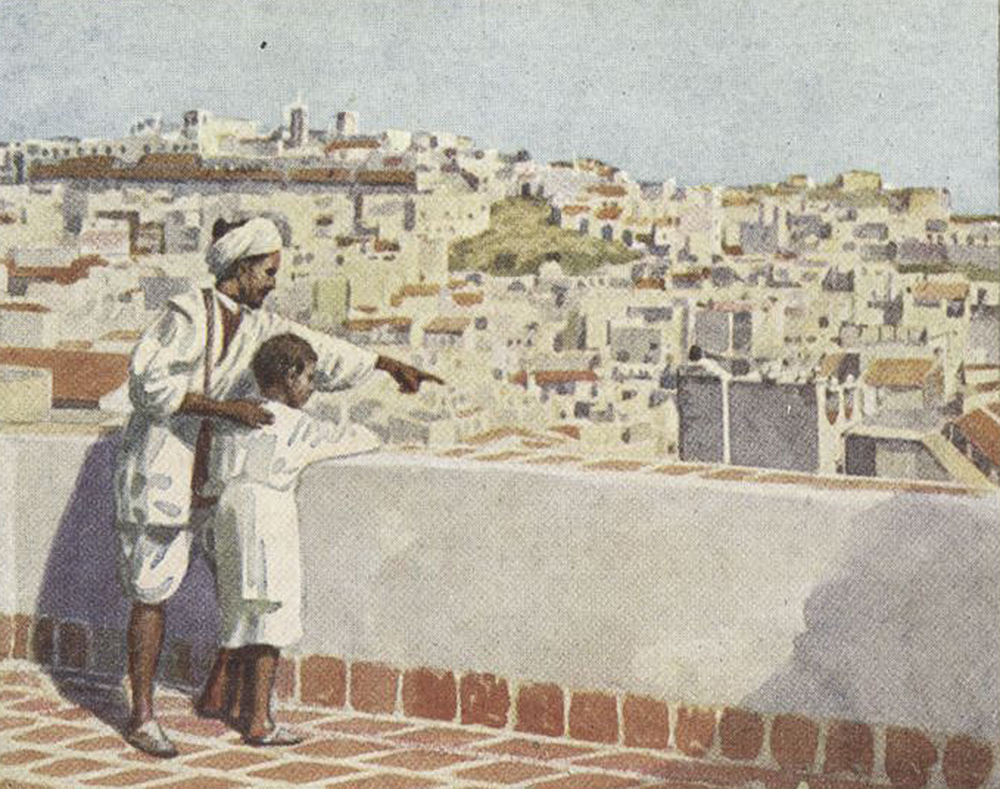

Choukri believed Bowles was afraid that the Moroccans he knew were harboring a secret contempt for him. Choukri denies this disdain, but writes, “Many Westerners and Americans say that Tangier without Paul Bowles wouldn’t be Tangier. But which Tangier are they speaking of? No doubt they refer to the Tangier that had been adored by Bowles and his kind, when it was chic and life there was inexpensive, a place where money would seek you out without your having to look for it. They forget that it was Tangier that created and adopted them, and that precious few of them did anything to enhance its literary and artistic reputation.”

Many expatriates, surrounded by a romantic kind of precariousness that fixes the Beats and the Lost Generation in twentieth-century history, passed through Tangier in search of the clout of a literary scene rather than the economic opportunities that might have brought people like Choukri to the city.

William S. Burroughs first went to Morocco in 1954, after drunkenly killing his second wife Joan Vollmer in a game of William Tell while living in Mexico City. Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg followed Burroughs to Tangier a few years later. Other well-known writers also arrived: Gore Vidal, Jean Genet, Tennessee Williams.

From 1924 until its independence in 1956, Morocco was disputed territory, controlled by French and Spanish protectorates. The city of Tangier was the distinct International Zone of Tangier, under joint administration by France, Spain, and the United Kingdom. The neutral demilitarized space became a destination for gay and bisexual men. Laws were loosely enforced—especially for Americans and Europeans—while in many other countries, including the United States, homosexuality was criminalized.

Burroughs stayed in the Hotel Muniria at $15 a month until 1959, and he wrote The Naked Lunch during his time there. But his initial goal in coming to Tangier was to meet someone in particular. He had been inspired by Paul Bowles’ 1949 novel The Sheltering Sky, about a naive husband and wife who travel to North Africa and suffer tragedy as a result of their ignorance of the landscape and the people around them. After a 1931 visit at the recommendation of Gertrude Stein, Bowles moved to Tangier semipermanently in 1947 (his wife Jane followed the year after), and his work helped introduce English-speaking readers to the city. He ended up acting as something of an ambassador for American writers, and he knew and worked with many who passed through.

After the Beat writers left for Paris in 1959, Paul Bowles would continue to receive visitors in his Tangier apartment, though there were fewer of them. They included the Moroccan storytellers and writers Larbi Layachi, Mohamed Mrabet, Ahmed Yacoubi, and eventually Mohamed Choukri. For Bowles and others who could not read Arabic, the tradition of oral storytelling overshadowed the expanding literary scene in Morocco and across the Middle East and North Africa.

Bowles was not the first expatriate writer Choukri encountered. His relationship with the French writer Jean Genet works as a sort of morality play about the tension between locals and visitor artists. In 1968, when Choukri was thirty-three, a friend of his pointed out Genet on the streets of Tangier. Choukri introduced himself, and when they spoke, he took notes. Choukri describes sitting in the Café el Menara and having long conversations with Genet over glasses of mint tea about the Quran, The Bible, and Stendhal’s The Red and the Black. He asks if Genet has read anything by any Arab writers. Genet’s answer: only one, the work of his friend Katib Youcine. Choukri suggests well-translated writers Taha Hussein and Tawfiq el-Hakim, names that Genet doesn’t recognize. He says he hopes to read them soon.

A year later they meet again. The two talk at length about The Plague and the stylistic differences between Albert Camus and Sartre. Camus “writes like a bull,” Genet says. He keeps asking if Choukri has read his new novels, until Choukri finally asks, “Why don’t they bring out your works in a cheap edition like Le Livre de Poche, for instance?…You know most students can’t afford to buy your books.”

“I don’t know,” Genet says, adding, “It’s not my fault.”

Another day, Choukri brings along a copy of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot and several Arabic literary magazines. He gives Genet an introduction to Russian literature; Genet says he’s not allowed into Russia. Both authors seem to enjoy the literary back-and-forth, but it’s Choukri who’s translating for Genet, bringing him books, and waiting in the café hoping he’ll come back.

One of the magazines Choukri shows Genet is al-Adab, a publication out of Beirut that by then had published two of his own stories, “Violence on the Beach” and “Herbs of the Dead.” His fiction sits somewhere between family drama and proletariat parable, depicting the struggles of poor families, the indignity of not finding work, the fear of hunger.

Choukri is very capable in French: he speaks easily with Genet and translates for him in their conversations. He is reading the novels he mentions in French and in Arabic. Many of the characters in In Tangier are multilingual through opportunities afforded by wealth or education, and in this way Genet and Choukri stand out—both men grew up poor and began their literary careers by writing about being young thieves. Choukri was illiterate until he was twenty. He grew up in extreme poverty in Oran and Tetouan in the Rif—a mountainous region populated mostly by Amazigh people—and in nearby Tangier, moving wherever there was work. When he was very young, his father killed his younger brother Abdelqader and brutally abused Choukri and his mother. The family moved from town to town in search of stability, and eventually Choukri ran away from home and found himself alone in Tangier. He spent years with barely any money, picking up odd jobs and stealing to make a living. In his memoir For Bread Alone, he describes his constant hunger and the frequent threat of violence, whether from other thieves or Spanish police. He intended the book as a kind of collective autobiography of the Amazigh poor in Northern Morocco, and the result is a grotesque text, describing a huge amount of inequality in a city that played host to Spanish soldiers and tourists, some of whom used their economic status to prey on boys like Choukri.

Once when he was twenty, Choukri was drinking with friends who worked and socialized in a nearby brothel and the police burst in and arrested them. One cold morning while he was jailed, a friend shared a few lines of a poem by the Tunisian poet Aboul-Qacem Echebbi: “If someday the people decide to live, fate must bend to that desire / There will be no more night when the chains have broken.” Echebbi was a political writer: one of his poems became the Tunisian national anthem, and several anticolonial struggles, including the Algerian Revolution, drew on his work. In the Arab Spring of 2011, his poems were shouted during protests in Tunisia. Choukri was so moved by the poem that he decided to go to primary school to learn how to read and write after he got out of jail. It was 1955, and the Moroccan people were fighting for independence.

This was the story that Paul Bowles wanted to translate. One night in 1972, the prolific Oxford-educated translator Edouard Roditi brought Choukri to Bowles’ home and introduced him: “He’s a Moroccan writer from the Rif. He recited some of his stories to me and their content is good. I hope that you might translate some of them for him.” Bowles had already translated stories by Larbi Layachi and Mohamed Mrabet, working with the British publisher Peter Owen to publish the stories in English. Mrabet (who worked as a bartender at the Hotel Muniria) and Layachi were oral storytellers; they had recorded tapes for Bowles in Moroccan Arabic with Spanish substitutions where necessary.

While visiting Bowles in Tangier, Owen suggested Choukri write an autobiography. Choukri immediately said he already had a manuscript at home, surprising the other men, who quickly drew up a contract for the three of them on Bowles’ typewriter. In Paul Bowles in Tangier, Choukri admits he “hadn’t yet written a sentence” of the book that would become For Bread Alone, but explains that he had been meaning to do so once he had “achieved some literary renown.”

He started writing in earnest. He would write during the day and visit Bowles at night, and the two would translate. In his introduction to the short-story anthology Five Eyes, published in 1979, Bowles writes that if he had understood how difficult working with Choukri would be, he would not have agreed to translate his memoir.

Choukri had written his text in Arabic, a language Bowles could neither read nor speak. Bowles admits that Choukri, despite knowing no English, did most if not all of the translating, via Spanish and sometimes French. Though Five Eyes includes stories by four other contributors, much of the introduction is dedicated to revisiting the long days the two spent working on the floor of Bowles’ home in 1973. He creates a caricature of Choukri as a man obsessed: “He sat beside me, in order to see that I was making a word-for-word version of his text. If he noticed an extra comma he demanded an explanation. I was driven to reiterating: But English is not Arabic! Finally we devised a modus operandi which involved our sitting on opposite sides of the room.” Bowles writes that he longed to return to the “smooth-rolling Mrabet translations”—to work with an author who had “no thesis to propound,” unlike Choukri.

Bowles’ translation downplays several of the more political moments in the memoir. In particular, when Choukri discovers the liberatory power of literacy, Bowles seems to invent a contradictory scene where Choukri’s friend—instead of asserting as he does in the Arabic edition that Choukri can also learn to read and write—asks what good reading and writing are in jail anyway. At points where the Arabic text makes clear that Choukri’s motivation is hunger and his alienation is economic, Bowles’ English version presents him as more of a listless nihilist. Even the title For Bread Alone is a strange fragment of elevated semireligious language—the original title, Al-Khubz Al-Hafi, just means “plain bread.”

Paul Bowles in Tangier is the longest of Choukri’s three books on writers who visited the city. He writes about their day-to-day interactions but also discusses at length Bowles’ ideas about Tangier, quoting from his novels and interviews. The text is half diary and half musings on the American writer’s legacy in Tangier. Choukri says that Bowles believed in the distinction between “tourist” and “traveler” outlined in The Sheltering Sky. For Bowles, “tourists,” aided by the proliferation of air travel, were destroying the parts of the world they passed over. In contrast, “travelers” have no definite home and engage more deeply in the culture around them. Choukri writes that if this were the case, the “true traveler disappeared in the twenties and thirties.”

Choukri’s frustration with the way self-defined expatriate artists saw Tangier continued to grow. He believed that the city had helped them to create work and that they had abandoned it in return. He wasn’t alone in his anger. Mohamed Mrabet and Bowles fell out with each other in 1996, after Mrabet accused Bowles of stealing royalties.

In May 2018, Sudarsan Raghavan found Mrabet and interviewed him for the Washington Post. Mrabet said the Beat writers “caused Tangier to die,” and that he was never a friend of Bowles’: “I was only working for them.” Choukri wrote that Bowles felt the same way toward Mrabet, saying in 1993, “He was never my friend…He was an employee like all of those who worked for me.” Before that, in 1981, Bowles said that expecting depth and reciprocity from a relationship with a Moroccan would be “like expecting a boulder to spread its wings and fly away.”

After arguments about translation, there were arguments about royalties. Choukri demands to know why Bowles would work with a “vampire” of a publisher like Owen and Bowles says he has little choice. But what really seems to trouble Choukri in the notes in Paul Bowles in Tangier is the way Bowles had helped to mythologize Tangier. Despite his distaste for Bowles’ attitude toward the city and its inhabitants, he also says of Paul and his wife Jane that “their nostalgia for the city’s lost innocence was justified. Their ruefulness was authentically rooted in Tangier’s past, a past they themselves had experienced.” Choukri and Bowles both came to live in the city in the 1940s. They were both there when Morocco gained its independence, and both lived through the tourism boom of the 1960s and the political upheaval of the 1970s. Choukri’s journals paint Bowles as nostalgic for the apolitical Tangier of his youth, and he quotes from Bowles’ 1952 novel Let It Come Down: “It was one of the charms of the International Zone [Tangier] that you could get anything you wanted if you paid for it. Do anything, too, for that matter—there were no incorruptibles. It was only a question of price.” While Bowles and others complained that Tangier had become too European, Choukri didn’t want them to forget that in his childhood he would venture into the European neighborhoods only because their garbage cans were more plentiful. Yet outside his memoirs, in the conversations he describes with his fellow writers, Choukri speaks very little of his own childhood experiences in Tangier, even as he tries to peel apart how Bowles sees the city.

In his memoir, Choukri describes selling newspapers, shining shoes, working in a café and in a brick factory. His mother despairs when his father is arrested for deserting the Spanish army—he had been out bartering and “had refused to sell a blanket to a Moroccan soldier who wanted it at a very low price, and the soldier had denounced him to the authorities.” His mother prays and visits the fortune-teller; she stops eating. Choukri visits his brother’s grave and takes a sprig of glossy myrtle he finds growing on another to place on it, but his horrified mother makes him put it back. When they move to another town, “I remembered Abdelqader’s grave. No one would put water on it, or sprigs of myrtle, and there were still no tiles around it. His grave will be invisible among all the others. It will get lost, the way little things always disappear among the big ones.”

Choukri never says whether he believes Bowles is a tourist or traveler or something else entirely, even though he was often deeply critical of the American writer. Ultimately, he acknowledges that there is a kind of truth in the vision of Tangier Bowles provided the West, even if it remains incomplete. The Tangier Bowles fell in love with could not have existed without the Tangier Choukri scrounged in. The romantic vision of the city survives because its vices and excesses are much more palatable than the repercussions visible in For Bread Alone.