Military Telegraphic Corps, Army of the Potomac, Berlin, Maryland, October 1862. Photograph by Alexander Gardner. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Florance Waterbury Bequest, 1970.

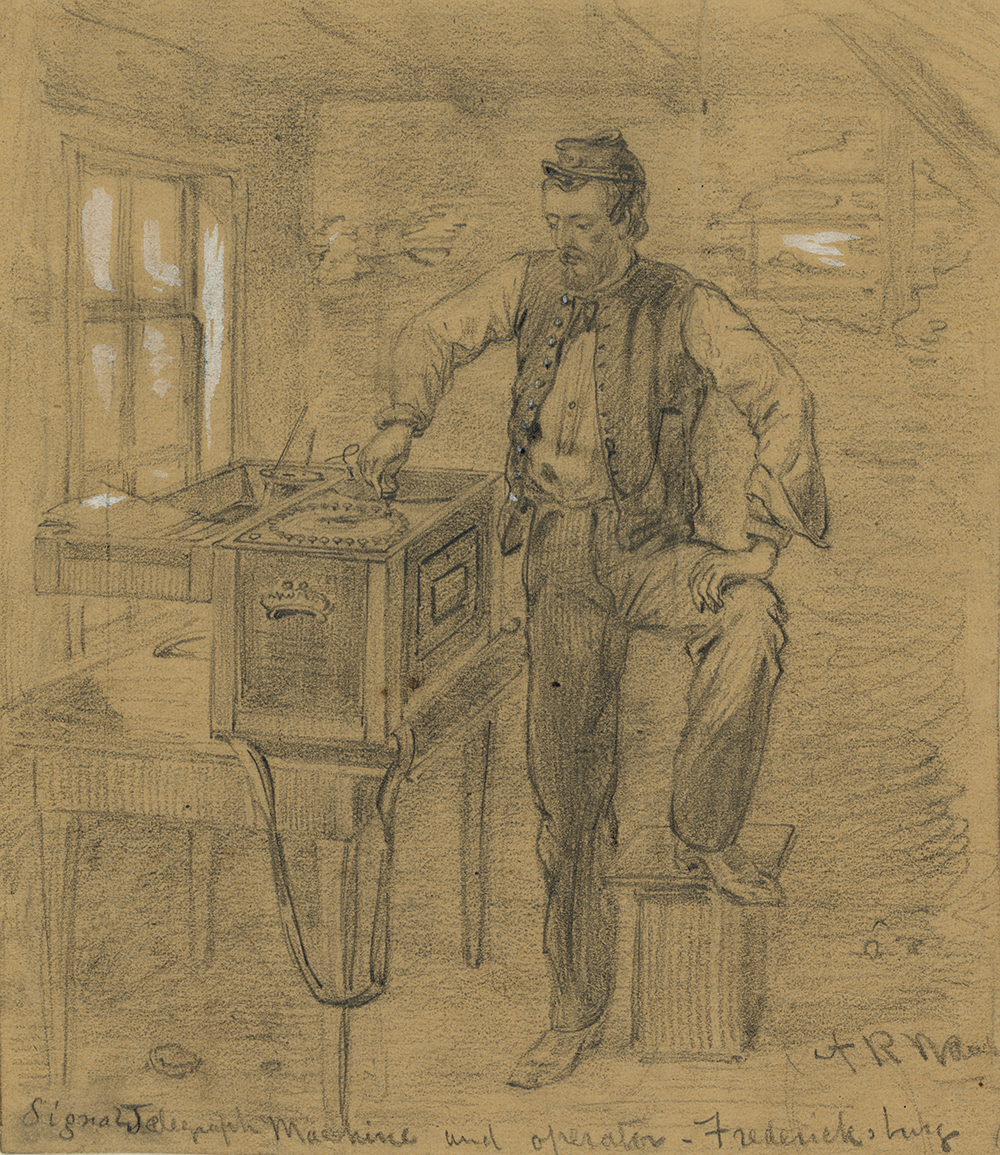

The first person to see things unfold was often a new kind of prophet—the telegraph operator. Like prophets of old, telegraph operators “saw” the future by hearing it and used a special language to read invisible signs and translate their meaning for society. The Civil War put the skills of telegraph operators in high demand. When Washington, DC, requested the best operators that the Pennsylvania Railroad could spare, Andrew Carnegie personally escorted his four best men to the capital. One of them, David Homer Bates, recalled the stress of waiting for arriving dispatches. His title, “operator,” privileged the slim fraction of time he spent tapping message on the machine. “Listener” was a more accurate description of his work. He and other operators spent endless hours straining to hear approaching news. As Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs testified, “I have seen a telegraph operator in a tent in a malarious locality shivering with ague, lying upon his camp cot with his ear near the instrument, listening for messages which might direct or arrest movements of military armies.” Operators embodied the tortured position that the war imposed on all Americans: all they could do was wait for the war to unfold.

Civil War expectations imprisoned Bates. At the start of the war he worked at the Navy Yard near Washington, DC. Authorities placed an armed sentry outside the door to his solitary telegraph office. No one was permitted to disturb the operator. “These orders were obeyed literally, and for four days I was virtually a prisoner,” Bates recalled. The guard passed meager meals to him. Bates waited and waited. Unable to stand it any longer, on the fifth day he locked the door, opened a window, and escaped. When he returned and unlocked the door, the sentry appeared and said he would shoot Bates if he repeated the stunt.

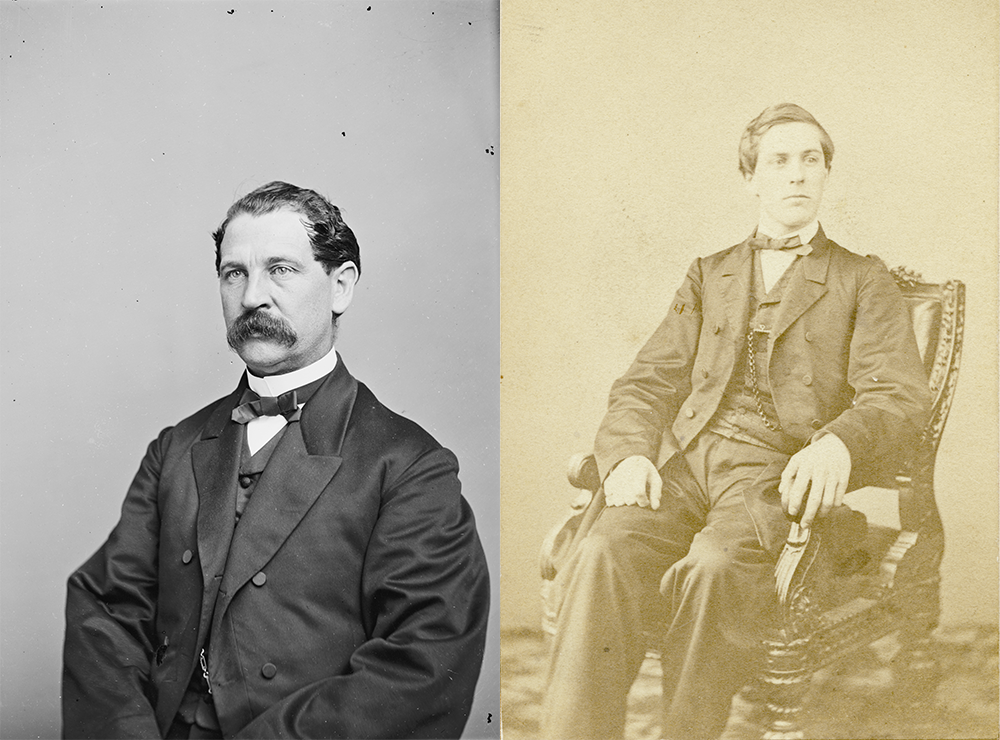

The strain of waiting for the future to arrive took its toll on men in the telegraph office. The first superintendent of telegraph operators in the War Department, John Strouse, worked himself to death. He began the war in poor health and did not last a year. The second superintendent resigned instead of facing the same fate. The third, Major Thomas Eckert, was a titan, physically and mentally. As a young man he traveled from Ohio to New York City to see Morse’s invention in person and then built his own telegraph from memory when he returned home. At the start of the war, Eckert escaped Confederate warrants for his arrest as a spy. When a War Department clerk bought cheap iron pokers, Eckert proved their inferiority by breaking them over his flexed forearm. Only men like Eckert survived as telegraph operators. Like fortune tellers and spiritualists, operators mediated worlds, a position that overtaxed their bodies and minds.

Bursts of sound interrupted tense expectations when a telegram arrived over the wire. The message came, one letter at a time, punctuated by dramatic pauses. As the operator transcribed the dispatch from Morse code to English, he capitalized words that he deemed important, because the message did not appear in distinct thoughts and sentences. Instead of unfolding in order with syntax, the message arrived as a matrix of words with five, six, or seven columns and lines. These blocks of text included “blind words,” extra text intended to confuse enemy interceptions. A keyword in the message revealed the order and direction in which the matrix should be rewritten and transmitted. “For instance,” Bates explained, “a certain keyword would represent the combination of seven columns and eleven lines and the route would be up the sixth column, down the third, up the fifth, down the seventh, up the first, down the fourth, down the second.” The meaning of the message emerged by following this trail and then discarding blind words and keywords. The future arrived as nonsensical garble and the operator literally deciphered it.

Uncertainty prevailed because even decoded messages contained ambiguous clues about the future. The truncated prose of telegrams could torment a recipient. A telegraphic messenger woke Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. the night after Antietam to announce: “Captain Holmes wounded shot through the neck thought not mortal at Keedysville.” The message haunted Holmes for days. Was his son’s wound “Thought not mortal, or not thought mortal,” he wondered. As the doctor rumbled south on a train, locomotion stirred thoughts about the wound. “Windpipe, food-pipe, carotid, jugular, a great braid of nerves, each as big as a lamp-wick, spinal cord.” A bullet through the neck ought to kill at once. For days Holmes had only the same twelve words from the telegram to interpret his son’s fate.

The speed of telegraphy could transmit the trauma of a battle unfolding. On April 13, 1861, James Garfield and other Ohio state senators adjourned to huddle around a telegraph operator while news from Fort Sumter arrived. Garfield tried to describe the “terrible excitement and suspense” he felt. For hours on end, everyone was captive to the silent oracle, waiting for the future and speculating about it. To pass the time, Garfield wrote a letter describing the unfolding battle. “An hour ago a telegraphic dispatch announced that the war steamers had crossed the bar amid a storm of fire from the batteries, and that a flag of distress was hung out from the walls of Sumter, and that the whole interior of the fort was enveloped in dense smoke, indicating that it had taken fire from the red-hot shot from Moultrie,” he wrote. The senators spread a large map of Charleston harbor across the table and Henry B. Carrington, adjutant general of Ohio, described the scene. Garfield could “almost see the battle.”

Telegrams about the surprise attack of the Confederate ironclad Virginia produced a similar sensation among Abraham Lincoln’s cabinet. The telegraph operator seemed to see the naval action in real time and relay its effects and emotions.

She is steering straight for the Cumberland—the Cumberland gives her a broadside—She keels over—Seems to be sinking—No, she comes on again—She has struck the Cumberland and poured a broadside into her—God! The Cumberland is sinking—

After the Virginia sank the Cumberland, burned the USS Congress, and ran the USS Minnesota aground, it threatened to steam up the Potomac and shell the capital in forty-eight hours. While the city raced to block the river, Lincoln and his cabinet stood in the War Department telegraph office in suspense waiting for word of the approaching ship. When a telegram from Major General John Wool reported that the USS Monitor arrived and “will proceed to take care of the Merrimac,” the suspense of expecting the Confederate warship in Washington was replaced by the suspense of awaiting the results of the first ironclad battle in history.

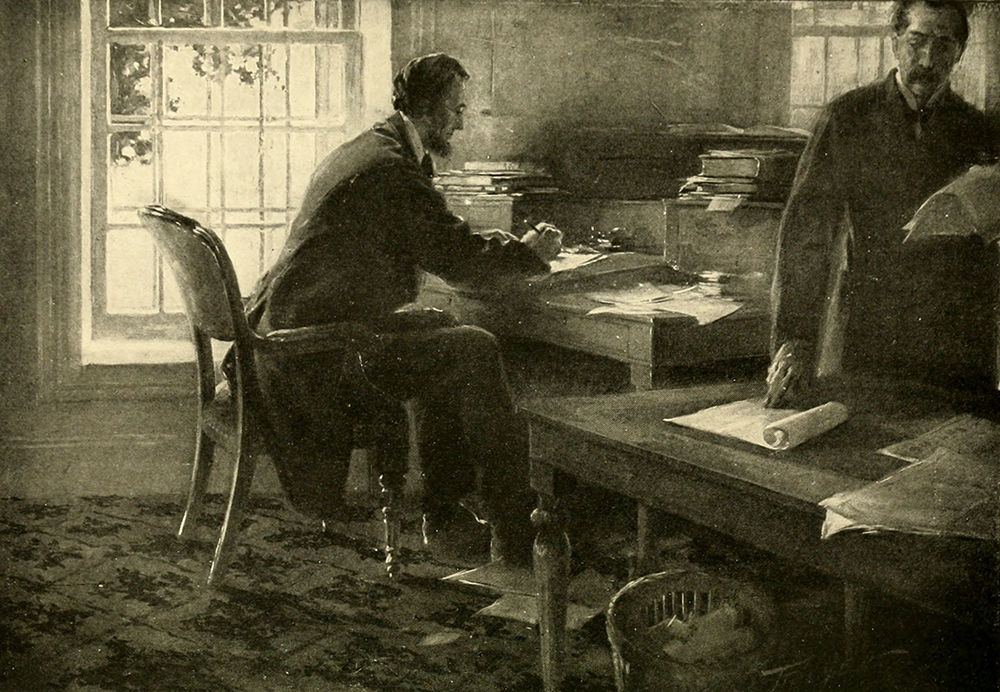

Lincoln, who expected the future by temperament, haunted the telegraph office. Most days he left the White House, walked to the War Department, and sat at Eckert’s desk, waiting for the future to unfold. “I believe I feel trouble in the air before it comes,” he told his aide John Hay in September 1863 after spending a night in the telegraph office reading dispatches from the front. While battles raged, Lincoln punctuated tortuous silences with short messages, like “Colonel: What news?” During the summer of 1862, he sat at Eckert’s desk and wrote on foolscap. Like the operators, Lincoln wrote in short bursts and long pauses. Arriving telegrams interrupted his work, but the silence of the place provided a better writing space than the White House. Each night, Eckert locked Lincoln’s writing in his desk drawer without reading it. Once while writing, Lincoln looked out the window and spotted a giant spider web between the windowsill and portico. Eckert joked that the operators called the colony of spiders “Major Eckert’s lieutenants” and assured Lincoln that they would report soon. “Not long after a big spider appeared at the crossroads and tapped several times on the strands, whereupon five or six others came out from different directions.” When Eckert and his men looked at the web, they saw operators and wires transmitting messages. Lincoln did not share what he saw in the web. Maybe he saw the war with its web of contingencies touching everywhere and restricting everyone. Perhaps he saw how slavery ensnared the nation. Sitting in the telegraph office, waiting for the future in 1862, Lincoln was writing the Emancipation Proclamation.

It seems paradoxical that Lincoln, the Great Emancipator, attributed unfolding events to God or Fate. If any individual could claim control of the war, it was the president. Yet he explained, “I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me.” When the war entered its third year, “the nation’s condition is not what either party, or any man, devised or expected,” Lincoln said. “God alone can claim it.” Historians have attributed Lincoln’s fatalism to a number of factors: melancholy, folk culture, the deaths of loved ones, republican jurisprudence, and the war. All these factors and more influenced him, but his temporality preconditioned how he understood things. Because he lived time with expectancy, sensing how the future approached him like waves reaching a shore, Lincoln focused on external forces, invisible elements that affected people and made history.

With victory imminent at the start of his second term, Lincoln still favored expectations over anticipations of the future. “With high hope for the future,” he ventured “no prediction in regard to it.” Instead Lincoln recalled how the war consumed everything four years ago. “All thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it, —all sought to avert it.” And yet “the war came.” The sentence did not assign blame to either section for causing the war, but it also expressed expectancy. The war came to the present, because God willed it. Harriet Beecher Stowe believed the Union fought on God’s side. Northerners like her son sacrificed their futures to help God punish southerners. Lincoln had a different vision. His God waged a separate war for “His own purposes.” The entire nation was guilty of slavery, and God was chastening both sides “until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword.” Lincoln knew people were “not flattered by being shown that there has been a difference of purpose between the Almighty and them. To deny it, however, in this case, is to deny that there is a God governing the world.”

From Looming Civil War: How Nineteenth-Century Americans Imagined the Future by Jason Phillips. Copyright © 2018 by Oxford University Press and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.