Shock Dog, by Anne Seymour Damer, 1782. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Barbara Walters gift, in honor of Cha Cha, 2014.

On a Thursday morning in February 1836, sixty-eight-year-old Clara Wheatley Pope paid a visit to the residence of the architect and Royal Academician Sir John Soane at Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Soane was not at home, but this was of little concern. The object of Pope’s visit was artistic—she had come to see a painting. Later that day, she wrote to Soane, with a wax seal bearing her name:

My dear Sir,

I called this morning to look at a picture, said to be painted as a likeness for you, I grieve to see such a caricature, placed in the room of so celebrated a society as that of the Literary Fund, for it will be the means of handing down to posterity a vulgar, coarse representation of a very different character. I am aware of the difficulty of accomplishing even a bad picture, but in my humble opinion, a portrait, for the constant eye of the public, ought not to be so detestable, and horrible, as the one I have just seen.

I know not who has painted it, but I should be sorry to be obliged to employ the same person to paint any friend of mine, pray pardon my presumption in thus making my remarks, but anxiety for your future fame makes me add that could I afford it, I would purchase the picture, throw it into the fire, and annihilate it forever.

Having for so many years seen such a different Sir John Soane, my impatience would not allow me to withhold the sentiments of your obliged old friend,

Clara Maria Pope

Pope wrote not only out of friendship, but from experience. Between 1796 and her death, she exhibited fifty-five narrative, portrait, landscape, and still-life works at London’s Royal Academy, while contributing to shows at the British Institution in 1807 and 1829. Throughout her long career, she was employed to design elaborate plates for botanical publications, saw one of her exhibited portraits quickly become a popular print, and was persistently praised by the London press for “her usual style of excellence.” Pope’s many pupils included Princess Sophia of Gloucester and, alongside Soane, the Academician Joseph Farington was her constant advocate and friend. She married twice—each time, an artist—and one of her daughters taught art as well.

Pope’s missive of February 1836 is one of several that survive between Pope, her second husband, Alexander Pope, and Soane. The letters exhibit a thoughtfully informed engagement with the British art world in the 1830s, a world they had all helped to form. They provide a window onto Pope’s financial navigation of London’s cultural institutions, as well as her reactions to ongoing developments and opportunities. Her harsh aesthetic judgment of Soane’s portrait, along with her vocal concern for “posterity” and “future fame,” reveal a penchant for candid communication and a belief in art’s ability to affect historical legacies. Most of all, they impart the self-confidence and self-consciousness of a forty-year-long career in the arts, a professional status rarely associated with English-women of her era.

Clara Pope seldom appears in historical accounts. However, her extensive career, widely recognized by her contemporaries, belongs to a much larger story: one that sees the unprecedented rise of women’s public, professional artistic activity in Britain and France. Pope was one of more than nine hundred women who exhibited their art in London during her lifetime, from the city’s first public show in 1760 through to 1830. In Paris, at least four hundred women exhibited their art publicly over the same years. These women worked extensively to have their art displayed in each of their nations’ most prestigious venues, institutional spaces that were vetted by juries composed entirely of men. By exhibiting their paintings, drawings, sculptures, and, occasionally, prints and enamels, they helped to shape each nation’s visual currents at pivotal junctures of revolutionary change.

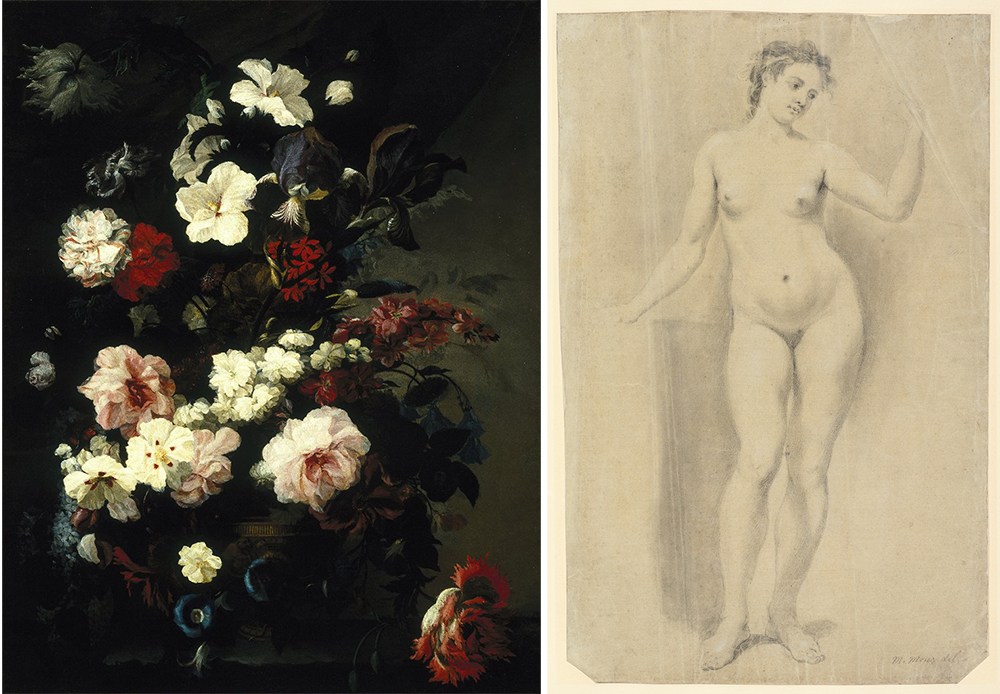

By the 1830s British artists had learned to navigate an art world that was frequently in flux. Over the course of the previous seventy years, London had experienced a period of radical cultural growth, which included the foundation of the city’s first exhibition venues and attendant efforts to promote a distinctively British school of art. Women have not featured in this story. Instead, their place in the London art world has long been characterized with reference to Johan Zoffany’s canonical c. 1771 painting, The Portraits of the Academicians of the Royal Academy. In this group portrait of the Academy’s thirty-six founding members in a painter’s studio, its two female founders, Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser, appear only as portraits placed high on the wall, a double-edged acknowledgment that they were part of this group but that their sex prevented them from participating in live, nude figure-drawing classes. Zoffany’s painting has thus widely been used to illustrate the novel public recognition of these women as artists while ultimately highlighting a much larger practice of exclusion. This reading, in turn, has repeatedly reinforced a long-standing narrative in which Kauffman and Moser were anomalies: that, since women were limited in their artistic output by restrictive moral codes and a consequent lack of training in figure drawing, they were largely excluded from London’s art institutions and the professional status open to their male contemporaries.

But there was more to the experiences of these women and their peers than exclusion and marginalization. Moser and Kauffman themselves may never have attended formal figure-drawing classes, yet a detailed drawing of a nude woman signed by Moser survives. Even while being feted as a flower painter, the genre for which she remains known, Moser sought to study the human figure and, by the time she completed this drawing, had become highly proficient at depicting the female body. Kauffman, moreover, built a distinguished career as a painter of classical, historical, and literary scenes—paintings that centered on bodies, both female and male.

Female artists were a regular part of London’s public exhibitions from their inception, and the printed, visual, and epistolary evidence of their artistic production compels us to reconsider the standard narratives and gender conventions that have long been applied to the era. The nine hundred women who displayed their art in London’s public shows from 1760 to 1830 operated with an acute awareness of the art world, a willingness to experiment with visual precepts, a recognition of their own creative talents, and a steady determination to have their work placed on display.

The Royal Academy of Arts was established in December 1768 with a charter from King George III, a culmination of the competition that had stimulated and plagued the London art world throughout the 1760s. Its thirty-six founding members included Kauffman, Moser, and Sir Joshua Reynolds, who served as its first president. Designed to emulate similar, state-sponsored societies across the Channel and, again, to promote a native British school of art, the Academy declared its “principal object” to be “the establishment of well-regulated schools of design…[with] that instruction which hath so long been wanted…in this country” and “an annual exhibition of paintings, sculptures, and designs, open to all artists of distinguished merit, where they may…acquire that degree of fame and encouragement which they shall be deemed to deserve.” Women were not allowed into the Academy’s Schools until the 1860s, and a third female artist was not admitted to its ranks until 1922. Still, from 1769 to 1830, over the course of its first sixty-two exhibitions, 3,612 works by more than seven hundred women graced its walls. Their art was not limited by genre or to “amateur” media—in fact, it largely reflected the range of works exhibited by men.

From the outset, the founding Academicians aspired to establish an organization explicit in both its educational purpose and standards of display. The Academy’s early years have been studied at length; most relevant here is the way in which it aimed to distance itself from London’s other venues by enforcing strict submission criteria. In its endeavor to foster a native British school, it prohibited copies from its inaugural show and, in 1771, further forbade items of “needlework, artificial flowers, shellwork, or anything of that kind,” a tenet repeated in its notices for decades. The evolution of this rule implies that the Academy was bent not only on separating itself from what would soon be considered “amateur” art and the societies that did allow such works, but especially on reducing the openness of its shows to women. Coupled with women’s exclusion from its schools, this has led scholars to ascribe the Academy a deeply exclusionary stance on gendered lines. And yet exhibition catalogues and reviews reveal the omnipresence of women in the annual show. Ultimately, and likely contrary to its intentions, rather than dissuading female artists, the Academy’s restrictions helped women to establish a mainstream, public presence, as the works they submitted, by requisite, had to mirror the types and quality of works made by their male peers.

Women were constant participants in the Academy’s show from 1769, and their presence immediately grew. In the inaugural exhibition, four women contributed eight of the 136 total entries, comprising 5.9 percent of the works displayed: Moser, Kauffman, and two anonymous honorary exhibitors, one of whom Horace Walpole identified as Susan Tracy-Keck, a maid of honor to the Princess Dowager of Wales. Moser exhibited two flower pieces, one in watercolor, one in oil, and the honorary works were a crayon portrait and a landscape drawing. Kauffman showed four classical-history scenes, three from Homer and one from Virgil, for which reviewers singled her out as a “young lady of uncommon genius and merit.”

In 1780 the Academy relocated to Somerset House, where it would remain until 1837; women maintained a regular presence throughout the decade. London flourished in these years, which further helped to foster the Academy’s growth and generally positive reception—a critical response that included these female exhibitors. When Maria Cosway first exhibited in 1781, critics commended her compositional promise and “great delicacy of execution.” Upon the debut of the sculptor Anne Seymour Damer in 1784, a reviewer marveled, “The oddity of her achievement is striking!—The marble statues from a female hand!” By the end of the decade, Damer’s practice as a sculptor remained “odd,” “striking,” or, perhaps, threatening enough to inspire a biting visual satire in which she appears to castrate an oversized, sculpted nude Apollo—explicitly targeting not only Damer’s sex, but the sexual implications of her artistic practice, with its perceived threat to prevailing norms of masculinity.

Then, a few years into the French Revolutionary Wars, the presence of women at the Academy surged. Initially, the British were swept up in the excitement caused by the events of 1789, waxing lyrical on the rapid political developments and rushing to Paris to witness the extraordinary overthrow of what had been perceived for so long as a strong and staunchly absolutist state. Yet by the mid-1790s, as Britons observed the changing and steadily more violent nature of Revolutionary events, radical and conservative sentiments gradually aligned on an anti-French front, and did so across gender lines; as patriotic fervor intensified, rising numbers of women engaged with the war effort in new and novel ways. In these same years, women began to exhibit their art in London as never before. At the Academy, the number of female exhibitors grew from seventeen in 1795 to sixty-four in 1799 and sixty-five in 1800; by 1800 the proportion of entries by women had ballooned to a new high of 9.4 percent. The number of new exhibitors rose from six in 1790 to twenty-five in 1799, and twenty-two in 1800—from 1790 to 1800, 123 women who had not exhibited at the Academy before displayed their art on its walls. A larger number of visitors saw these works as well, with attendance soaring to 59,110 in 1800. That year, in a Monthly Magazine article, the actress, poet, and novelist Mary “Perdita” Robinson hailed the cultural accomplishments of these women, boasting, “We have also sculptors, modelers, paintresses, and female artists of every description.” Robinson would have known that she and her peers had recently endured a much harsher public vetting, stemming in part from women’s increasingly conspicuous activity across London’s cultural sectors. In The Unsex’d Females, a Poem, published in 1798, the otherwise little-remembered conservative clergyman Richard Polwhele had unleashed a diatribe against the perceived assertiveness of an emerging group of women writers and artists in their public works and private lives; his prey included Robinson, the radical writer Mary Wollstonecraft, and Angelica Kauffman.

Albeit a minority population, and certainly aware of the cultural prejudices and institutional restrictions they invariably faced, women secured a presence as regular and fluid members of the Academic world in these years.

Kauffman and Moser participated in administrative decisions, voted in elections, and acted as judges for the granting of awards and traveling scholarships. While Kauffman did so by mail, Moser stayed active in the Academy’s social circles, often attended meetings, and, in 1794, received a vote for president. (Elections for the office of president of the Royal Academy took place annually following Reynolds’ death in 1792.) Farington relayed the ensuing confusion: “A contention took place about admitting [her] name on the books of the Academy. Barry supported the necessity for it. It was at last agreed to be omitted, as it was evidently intended as a joke, and if seriously she was not eligible.” In line with Farington’s commentary, this vote has largely been described and dismissed as either a joke or a criticism of Moser’s ambition, and for understandable reasons—no evidence suggests that Moser sought the position, it seems highly implausible that she would have accrued the necessary votes, and it is virtually inconceivable that the Academy would have considered electing a leader who could not attend its own schools.

As with Zoffany’s painting, there is, however, much more to this anecdote than mockery or reproof. Moser had just procured a large £900 commission from Queen Charlotte, and after decades exhibiting still could claim commercial clout. Implicit in this vote as the recognition—and perhaps some unease—that Moser had not only sustained a public artistic status but also had high connections and cultural influence, as did several of her peers.

Excerpted from A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France, 1760–1830 by Paris Spies-Gans, published by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. Copyright © 2022 Paris Spies-Gans. Reprinted by permission of the Paul Mellon Centre.