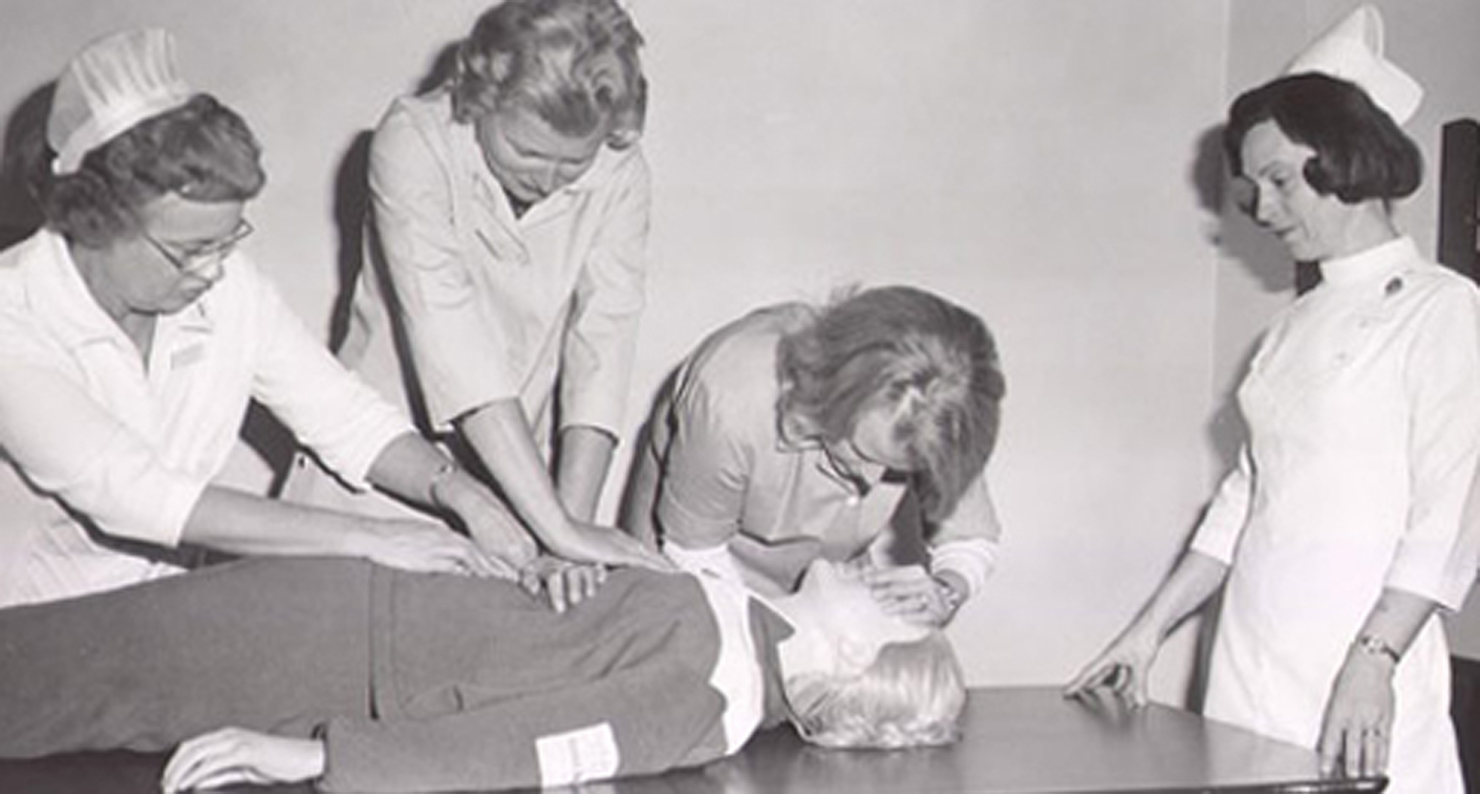

Nurses practice resuscitation techniques, c. 1960. Flickr Commons.

When the rescuers pulled James Blair out of the coal pit by his floppy limbs, hundreds of townsfolk watching the spectacle were certain he was a goner. Overcome by the noxious fumes from a coal pit fire, Blair had been unconscious for more than a half hour before his brave cohorts could climb down the ladder’s thirty-four fathoms to retrieve him. He had no pulse, his skin was icy, and his tongue lolled out of his gaping mouth.

Standing by was a surgeon named William Tossach, who would attempt something no medical man had dared in 1732. He put his mouth to the patient’s, held his nose, and blew with all of his might, causing the patient’s chest to puff out like a sail. Tossach described the results to his colleagues:

I immediately felt six or seven very quick Beats of the Heart; the Thorax continued to play, and the Pulse was soon after felt in the Arteries.

After an hour, Blair began to yawn and blink. Four hours later, he walked himself home.

When Tossach published his findings in 1744, he described what physicians now refer to as mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, and the discovery set the scientific community aflutter. The eminent Dr. John Fothergill reported of Tossach’s tale:

There are some Facts, which, in themselves, are of so great Importance to Mankind, or which may lead to such useful Discoveries, that it would seem to be the Duty of every one, under whose Notice they fall, to render them as extensively public as it is possible.

Prior to and alongside mouth-to-mouth, a bevy of resuscitation methods had been foisted upon the apparent dead. Bodies were rolled over barrels or dragged by their feet, feathers were inserted into throats, tobacco smoke was blown into rectums, and victims were forced to swallow various concoctions of spirits, vinegar, and urine.

Accounts of successful resuscitations inspired a zeal for teaching the new methods to the public, resulting in the 1767 foundation in Amsterdam of the Society for the Recovery of the Apparently Drowned (nicknamed The Dutch Society) and a 1774 society of the same name in Great Britain, which later became the Royal Humane Society. Impassioned annual reports from these groups trumpet that, “incredulity is changed to astonishment at restorations to life, which have hitherto been deemed beyond the power of mortals!” To this end, the Royal Humane Society began awarding medals of gold, silver, and bronze to those who successfully saved drowning victims. Philanthropic members also furnished sizable cash rewards to rescuers.

Perhaps members of the Royal Humane Society felt the need to offer such rewards because the prospect of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation was anything but enticing. While putting one’s mouth to the cold, blue lips of a stranger is always a distasteful prospect, the eighteenth-century mouth was a special horror to behold. Coffee, tobacco, and sugar were readily available in Europe, but dental practices such as the brushing of teeth and tongues were only starting to come into fashion, and even then only among the wealthy. This combination resulted in a perfect storm of halitosis and tooth decay. Any volunteers willing to attempt resuscitation under these conditions truly did deserve a medal for their bravery.

But there was a greater threat to the widespread adoption of mouth-to-mouth: the discovery of oxygen, and later, of carbon dioxide. Until Antoine Lavoisier discovered oxygen in 1778, the phlogiston theory reigned, which explained phenomena such as combustion or rust on a mysterious fiery element called phlogiston. Once it was known that the components of human inhalations and exhalations differ, bellows were seen as a more efficient way to deliver oxygen into the lungs than expired air, relieving would-be rescuers of unpleasant physical contact.

The breath of life was tested alongside the spark of life. As natural philosophers began experimenting with electricity, electrocution was used to revive the near-dead, with gruesome animal experiments attempting to put animals into, and hopefully return from, “suspended animation”. In 1858, the Hall method pulled on the arms and legs in a rhythmic fashion; one might recognize this technique as one employed in early cartoons. The Holger Nielsen method, where patients’ elbows are lifted from behind while they lie on the stomachs, appeared in the first Boy Scout Handbook in 1911, until it was phased out in favor of the current cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) method. With all of these competing methods, mouth-to-mouth resuscitation was relegated to a historical footnote.

Not until the 1950s did two American doctors, James Elam and Peter Safar, rediscover mouth-to-mouth and publish pamphlets to alert the public, though they were likely unaware of the work produced some two-hundred years prior. Safar also wanted to give the public a way to practice this technique, and approached toymaker Asmund Laerdal to create a life-size mannequin to teach CPR skills.

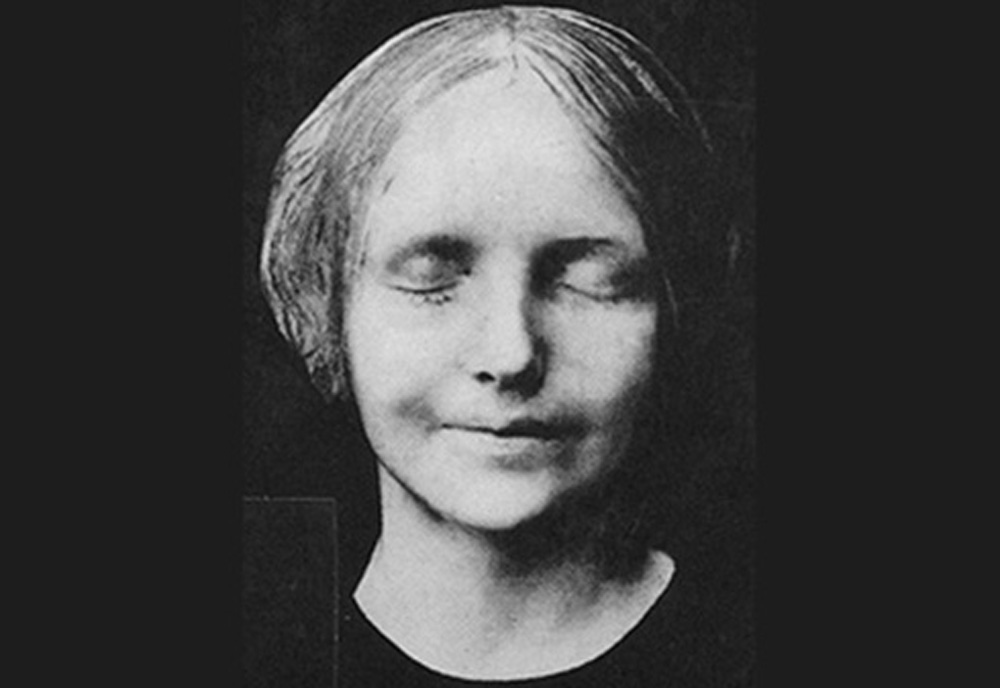

Safar and Laerdal understood that for the teaching tool to be effective, the experience had to be as pleasant as sucking face with a dummy could reasonably be expected to be. They decided early on that the mannequin should be a woman, and unlike the contorted visages of most actual drowning victims, she should have a beautiful and serene countenance. Laerdal was inspired by the mysterious death mask hanging on his wall to model his mannequin after a woman who achieved a peculiar kind of posthumous fame as the Inconnue de la Seine.

Not much is known about the life of the young woman who was fished out of the Seine River in 1880 after possibly committing suicide. But in death, she became a star. As the legend goes, the pathologist at the Paris morgue was so enamored with her lovely and enigmatic expression that he made a death mask. The face was then reproduced in plaster and quickly became a fashionable curio in homes across Europe. Women in early twentieth-century Europe fashioned their looks after the Inconnue; as a style icon, she was usurped only by the stars of early motion pictures. She went on to inspire works from the likes of Rilke,Nabokov, and Gaddis, and so too did she inspire the toymaker Laerdal.

Resusci Anne, as she came to be known, has been a staple of CPR training since she was created, with training rooms ringing with cries of “Annie are you OK?” to establish a victim’s non-responsiveness. While that phrase might bring to mind the Michael Jackson song “Smooth Criminal,” the American Heart Association would prefer potential rescuers to think of The Bee Gees’ disco hit “Stayin’ Alive.” In a series of recent public service announcements featuring television stars such as Ken Jeong (a licensed physician), actors wear Travolta’s signature white suit to inform the public that performing chest compressions to the beat of “Stayin’ Alive” will result in the perfect 100 beats per minute that the American Heart Association recommends.

What the American Heart Association no longer recommends is mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. In the mid-1990s, medical studies revealed that a technique called Hands Only CPR is just as effective at saving lives as mouth-to-mouth. When asked, a majority of citizens trained in CPR— and even most doctors and nurses—said they would prefer not to perform mouth-to-mouth on a stranger, and that even the willing tend to forget important elements of their training within six months. Doctors also suggest that doing both chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth is too difficult for one person, leading to rescuer fatigue and the potential for dangerous mistakes. Hands Only CPR, on the other hand, doesn’t carry the same social taboos as mouth-to-mouth. In fact, a survey conducted in 2013 shows that although only one-fifth of those surveyed know how to do Hands Only CPR, three-quarters of laypersons would be happy to give it a shot—especially if they don’t have to kiss you.