Turtle costume design for Alice in Wonderland, by William Penhallow Henderson, 1915. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Alice H. Rossin.

The victims of the crime were mute, helpless to plead their cause even before they had been turned into soup. But the green turtles in the hold of Captain Nehemiah Calhoun’s boat had a champion in Henry Bergh, one human determined to stand up for their kind. On a May morning in 1866, Bergh boarded the schooner Active, just arrived from Florida with a shipment of turtles for Manhattan’s Fulton Fish Market. Belowdecks, he found over a hundred large turtles stacked like living luggage. For weeks during their voyage north, the animals had been deprived of food and water. Worse still, the captain had flipped them upside down to immobilize them and had bound them together with a rope pierced through their flippers, creating wounds that still oozed after weeks at sea. In the turtles’ punctured limbs and glassy eyes, Bergh witnessed not only weeks of physical pain and deprivation but also “intellectual suffering.” He thought he saw tears falling from their eyes, dappling the deck below.

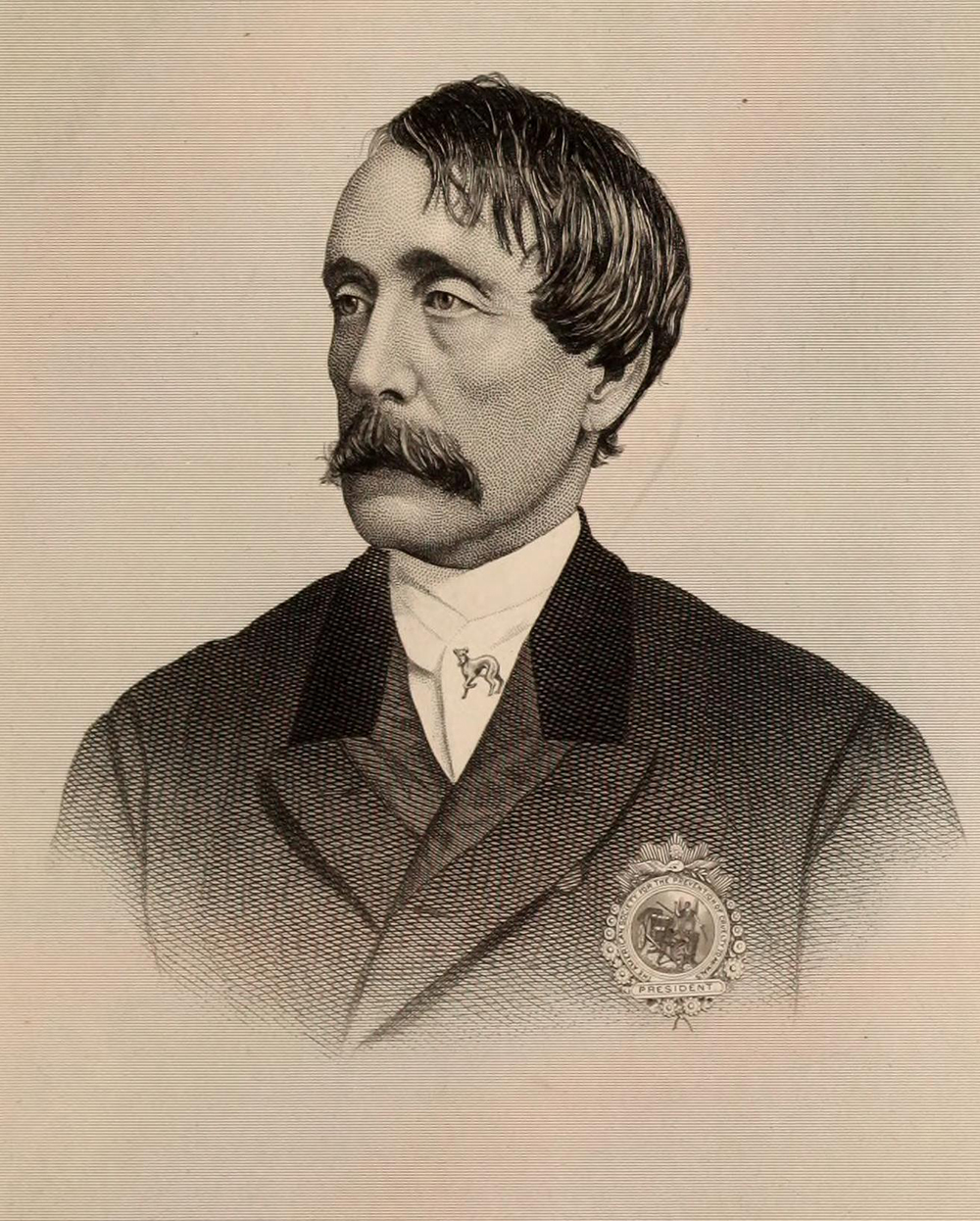

Only a month before, Bergh had founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in New York, an organization dedicated to ending humanity’s “gross ignorance, thoughtlessness, indifference, and wanton cruelty to…brute creation.” Bergh would spend the next two decades discovering just how hard it was to untangle animal rights from human privileges.

Henry Bergh was motivated not by an unusual love of animals but by a hatred of human cruelty. Fifty-three years old, he had come to this cause only recently. Heir to an industrial fortune, he had spent most of his career in a fruitless quest for literary fame. During a brief stint as a diplomat to Russia during the U.S. Civil War, Bergh had witnessed brutal treatment of horses by St. Petersburg teamsters that provoked in him something like a conversion experience. After visiting the leaders of England’s Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, founded in 1824, he returned to the United States determined to establish a similar organization.

The state legislature soon granted Bergh a charter for his new American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), then passed a law he had drafted, making it a crime to “maliciously kill, maim, wound, torture, or cruelly beat any horse, mule, ox, cattle, sheep, or other animal.”

Before 1866 twenty states and territories had passed anticruelty laws, focusing on the protection of livestock. Because these laws were rarely enforced, Bergh crafted a much stronger enforcement mechanism. The statute empowered his ASPCA to appoint its own “agents,” badge-wearing officers who were authorized to intervene in acts of animal cruelty, to call on police to enforce the law, and even to make their own arrests. This proved to be one of the law’s most important innovations, empowering Bergh not only to plead for better behavior but also to demand it. This law had teeth. As historian Susan Pearson puts it, the statute “made the crime consist more clearly of violence against animals themselves rather than the violation of property rights or disruption of the public order.” As Bergh interpreted his own law, that included the right of turtles to be protected from unnecessary pain.

Thus, Bergh considered Captain Calhoun a rank criminal for shipping his turtles in an “unnatural” position that seemed obviously cruel. But Calhoun protested his innocence, explaining that this was standard practice in the trade and the least harmful way to transport them. Their backs’ hard carapace protected them from the damage they would otherwise inflict on their softer bellies as they flailed for their freedom in the hold of a ship.

Bergh was not buying it. Exercising his authority under the new anticruelty law, he ordered two policemen to arrest the captain and his entire crew. The patrician Bergh—likely sporting his usual top hat and cane—led the disgruntled fishermen to the city court and jail known as the Tombs. There they would face a strange new kind of justice, a law that Bergh felt sure had granted even reptiles bound for the soup pot some measure of rights.

Long a staple source of fresh meat for sailors, turtles had the misfortune in the nineteenth century of pleasing the palates of wealthy Europeans and Americans, who found the gelatinous “green fat” under the turtle’s shell a particular delicacy. Among the various edible species, gourmands particularly hungered after the green turtle, a seagrass feeder that commonly grew to four or five hundred pounds, and sometimes twice that much. From Nicaragua to the Carolinas, hunters used nets and spears to capture thousands of these migratory animals each year. Or, when female turtles left the safety of the sea to lay their eggs on a moonlit beach, hunters capsized them, then either butchered them at their leisure or hauled them to holding pens before sending them on the long voyage to northern markets.

Wealthy men in New York expressed their passion for turtle meat by joining “turtle clubs,” convening each season for meals in which the reptile’s flesh formed the center of every course—soups, steaks, chowders, and salads. A single restaurant in New York cooked over 25,000 pounds of turtle meat each year and shipped its soup and steaks as far away as London. Since turtle dishes had become “the greatest luxury of the epicure,” as one observed, no friend of the animals could hope to disrupt the trade. “Turtles must and will be had.”

When Bergh arrested Captain Calhoun, he never meant to interfere with the turtle fishery. He liked to tell audiences that he was fond of turtles, but also turtle soup. Done humanely, taking an animal’s life was not an act of cruelty, as he saw it. “Otherwise the butcher exposes himself to this charge,” he reasoned, “and all who eat flesh are to a certain extent accomplices.” As he would explain countless times over the course of his career, the anticruelty law never questioned people’s right to use animals, only their right to abuse them.

But can one abuse an animal that has no feelings? At Captain Calhoun’s trial, the defense produced an expert witness, a Dr. Howard Guernsey, who testified that the “nervous organization” of turtles was “of the very lowest order,” making them incapable of suffering. In his view, piercing the creatures’ flippers and binding them with cord made no more impression than a human would feel from a mosquito bite. The source of Guernsey’s authority to speak on the physiology of turtles was not explained in the court records, but some measure of his reliability might be found in his explanation that “dying is not as painful as toothache.” He claimed to have “never seen any person dying in agony.” From this he reasoned that, if Bergh was correct in his claim that turtles died more quickly when placed on their backs, the poor creatures might count this a blessing.

Do animals suffer when they die? Do turtles have moral and legal standing? These matters were murky enough, but the debate in Justice Hogan’s courtroom was further muddled by confusion about some basic biological concepts. As one New York paper summarized the “knotty question” at stake in the trial, is a turtle an animal or a fish? The defense’s expert, Dr. Guernsey, located them in a middle ground between crustaceans and amphibians, “like a crab, lobster, or oyster.”

In this early test case of the anticruelty law, Judge Hogan’s skepticism was clear. Seeking to score a point against Bergh, the judge asked him if removing turtles from the water in the first place was not an act of cruelty. Pushed to its logical conclusion, he implied, a law preventing cruelty to turtles might deprive humankind of the pleasures of their flesh. Displaying a better grasp of biology than most in the courtroom that day, Bergh explained that sea turtles were not harmed by being removed from the sea because they lived a portion of their lives on land.

Bergh ridiculed the defense’s claim that turtles were not animals but fishes. For a century, experts in the new science of comparative anatomy had been proposing competing schemes for classifying animals. But none of them doubted that turtles belonged in the reptile family or that reptiles were animals. Like many wealthy young men in his day, Bergh had never bothered to finish college, leaving Columbia after two undistinguished years. But in court that day, he assumed the role of an exasperated expert. All of nature divides into three “kingdoms,” he lectured—animal, vegetable, mineral. If turtles are not “animal,” he asked, then which of the remaining choices might they be?

In addition to advocating their self-serving zoology, Captain Calhoun’s lawyers made a more plausible argument, suggesting that the new state law against cruelty to animals never aimed to include “lower” species such as turtles. Here was a valid legal question, and one that soon provoked a boisterous public debate about humanity’s moral obligation to other species. The new anticruelty law staked a radical claim that animals enjoy the right to be protected from avoidable pain and suffering. But even if humans accepted this idea in principle, did that duty extend to all creatures? Just how far down the chain of being did this protection against cruelty go? Bergh thought all the way down. When the “Great Creator” gave life to “the poor despised turtle,” He also gave it “feeling and certain rights as well as ourselves.”

Others howled in protest. If Bergh and his followers in the ASPCA aimed to defend “all animal life,” that slippery slope would lead them to an absurd concern for the well-being of toads and crocodiles, clams and mussels—even the pernicious mosquito. Bergh fought back in a series of letters and lectures, denouncing his foes as “brutal and unthinking people.” For him, the arrest of Captain Calhoun served as a visible and controversial test case for a wider moral claim he was making in defense of all Creation.

But Bergh’s arrest of Captain Calhoun was motivated less by his cosmic empathy for all living things than by his recognition that the anticruelty movement needed publicity and that newspaper friends and foes would be helpless to resist such a curious case. Like many other moral crusaders before and since, Bergh concluded that it was better to provoke the press’s ridicule than to wither under its apathy. He had not, in fact, stumbled across Captain Calhoun’s shipload of turtles accidentally, but had sought them out after reading of their arrival in a local paper. He had come to the Fulton Fish Market that day searching for a “first-class sensation.”

It worked. The case provoked public conversation about the “celebrated turtle case” in every city newspaper, in columns across the country, and in the streets as well. Here was “the excitement I desired,” Bergh wrote years later. “Within a week thereafter, a million of people, had read—and for the first time thought of the matter!”

Little of that thinking went Bergh’s way. Newspapers derided the “maudlin Bergh” for his “pathetic appeals” on behalf of lowly creatures. And a Manhattan saloon placed a large live turtle in front of its premises, cushioned on a bed of cornhusks, a pillow under its head. Above him the proprietor posted this message:

Having no desire to wound the feelings of any member of the “Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals,” or of its president, Henry Bergh, Esq., we have done what we could for the comfort of the poor turtle during the few remaining days of his life. He is appointed unto death, however, and will be served in soups and steaks on Thursday and Friday. Members of the aforesaid society and others are invited to come and do justice to his memory.

Days later the court declared Captain Calhoun innocent. Bergh’s only consolation came when the judge dismissed a countersuit that the captain had brought against him for “malicious prosecution and false imprisonment.” Bergh greeted this ruling as vindication of the right of ASPCA agents to pursue these cases without fear of being jailed themselves. Unwittingly, when the state legislature passed the anticruelty law, it issued Bergh and his deputies a license to provoke a public conversation about the limits of human power over other animals.

Excerpted from A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement. Copyright © 2020 Ernest Freeberg. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.