Siward Stone, Essex, by John Inigo Richards, eighteenth century. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

In just four years, from late in 1763 until 1767, Daniel Sutton made a fortune working single-handedly as an inoculator. He did not, as might have been expected, head to London to prosper among the well-to-do. As he had no medical qualification it might have been risky. And in any case, his experience working with his father had taught him that in country towns and villages there was a demand for inoculation, and not many country surgeons at that time were willing to offer it.

The village of Ingatestone in Essex that Daniel Sutton chose for his pioneer practice might look out of the way today, but in the eighteenth century it was a bustling stopover en route from London to Colchester and the port of Harwich. This was the Great East Road, which was thronged with wagons and carriages, many heading for Harwich on their way to board the boats which regularly plied the southern North Sea to Holland. The Harwich route was favored in 1763, when Daniel arrived in Ingatestone, for war with France had made the Channel crossing dangerous.

Travelers broke their journey at the inns that lined the main road through Ingatestone to change horses and spend the night. An advertisement for the sale of a lease on the Ipswich Arms and Chequers Inn in Ingatestone described it as “one of the capital roads in the Kingdom for coaches, post chaises, and drovers with pasture land, stables, and a Barn.”

Daniel hoped to attract a new kind of clientele to the village, those who would come and stay at the inoculation houses he established just a short distance from the main road. They could not pop in for a quick jab in the arm. On offer was the same kind of treatment that his father had established, with patients living in the inoculation house for up to a month. To make his practice more attractive, he would cut the time taken for inoculation and provide accommodation in a new and much more amenable way than was the common practice at the time. His patients would not be confined indoors but encouraged to enjoy fresh air while the pox developed.

Daniel was not known in the area and was aware that he would need some vigorous promotion to get established. This he did, as James Carrick Moore put it in his History of the Small-pox, “with the old trick of puffing handbills and boasting advertisements.” He began his campaign on November 5, 1763, with an advertisement in the Ipswich Journal:

This is to inform the publick

That daniel sutton, surgeon, has hired two very commodious houses in the parish of Ingatestone, Essex; in one of which (that stands retired, and near two miles from the town), he proposes receiving such persons as chuse to be inoculated by him for the smallpox. They are fitted up in a very neat and elegant manner, and will be ready for the reception of patients the beginning of next month.

As luck would have it, a new newspaper, the Chelmsford Chronicle, began publication just as Daniel began his promotion. He was quick to add to the Chronicle’s column inches with a boast that attracted a good deal of attention. His patients could

quit their bed or room and take the air at any one stage of the distemper, except a few hours, whilst they are breeding it; having on average not more than twenty pustules each; a practice essentially interesting and worthy of the attention of the public, particularly the Fair Sex; as by this method the face is effectually prevented from being disfigured. By communicating the smallpox thus favorably, the patients in general are enabled to return to fresh company in three weeks, or less; a circumstance which particularly affects the working hand etc.

By the end of his first year Sutton was raking it in. William Woodville reported in his History of the Inoculation of Smallpox that by the close of 1764, Sutton had earned 2,000 guineas: in today’s money perhaps £400,000. The following year he more than tripled this income to 6,300 guineas and was well on his way to becoming a wealthy man. A local archivist, E.E. Wilde, in a history of Ingatestone published in 1913, wrote:

Seldom can a young man have earned so handsome an income by his own handiwork in so short a space of time…For those years our old road and village must have been thronged with pilgrims on their way to the new and fashionable cure, the coaches filled to overflowing, and innyards crammed with vehicles and beasts of all kinds, from the lord’s smart chariot to the humble donkey of the cottager.

This was not a trade popular with the local innkeepers and burghers, however. No sooner had Daniel announced his arrival as an inoculator than the residents of Ingatestone were warned that he brought not prosperity but danger and potential disaster. Adjoining one of his advertisements in the Ipswich Journal in November 1763 was an invitation to get out of town.

information to the public

Whereas one Daniel Sutton has advertised that he has hired two houses in Ingatestone to inoculate the smallpox; this is to certify the public, that the neighborhood of Ingatestone is at present entirely free from the smallpox and tho the said two Houses stand about one mile distant from the Town, yet they are close to a much frequented road and necessarily must have such a communication with Ingatestone that the infection must be spread in time if the project should go on, the principal inhabitants of this and the neighboring parishes therefore are determined to give all the opposition thereto that the law will enable them to do; as infecting a Town of so much traffic will be to the detriment to the public, and may be easily proved a nuisance.

This was quite a common reaction to news that a doctor was setting up as an inoculator in a town or village where there had been no smallpox for several years. There was no law against inoculation. Daniel knew that very well and was not at all perturbed. He responded with an advertisement saying there was no prohibition on the use he was making of his rented houses. He practiced only as an inoculator and could not be threatened in the same way as country surgeons with a general practice, who might lose their standing in the community and their livelihood if they persisted in offering inoculation. The only time Daniel came close to censure was once when, at the height of his fame in 1767, he faced a charge in the larger nearby town of Chelmsford that he had started an epidemic of smallpox by bringing in infected patients.

A grand jury, a kind of tribunal of the good and the great in the town, considered the charge and dismissed it for lack of evidence. He was not the only inoculator in town who might have started an epidemic and Sutton was sure that the charge was malicious, cooked up by his rivals. But the criticism continued, with critical coverage in the press.

The proprietor of the Swan, the most prominent and popular inn, paid for his own advertisement in the Ipswich Journal on July 6, 1765, to dissociate himself from any of Sutton’s activities, announcing that: “For the future no letters or parcels whatever that shall be directed either to Mr. Sutton or his patients Will be taken in at the Swan aforesaid; neither will he at any time Hereafter furnish the said Mr. Sutton or any of his patients (during their stay with him) with any horses or chaises, upon any pretense whatever.”

Banishment from the Swan Inn was water off a duck’s back for Daniel. He was now established in Ingatestone with the wealth to buy a house called “Maisonette.” Daniel’s income no longer came solely from his local practice but from a franchise system, which copied that begun by his father. Such was his growing fame that he had requests from doctors practicing miles away in other counties to sign up as authorized Suttonian inoculators.

There is no record of what they paid for the privilege, but it is likely that Daniel drove a hard bargain. When a doctor was signed up they would get an endorsement in the local paper, which served to enhance Daniel’s reputation and promote the Sutton brand.

Not only were there Daniel Sutton acolytes everywhere, his father and four of his brothers were all advertising their special expertise so that in the 1760s, if there was a report by someone saying they had been treated by a Mr. Sutton, there was no certainty as to which one it might refer. But whichever one it was, you could be certain that the routine was the same, involving as it did a meticulous attention to detail. At the same time, the inoculator would not be nervous or anxious but brimming with confidence. That was a Sutton hallmark.

Just two years after he broke away from his father’s practice, Daniel had won for himself a reputation as the Suttonian inoculator. His rivals began to wonder what it was about his inoculation practice that was so appealing and, apparently, effective. One of those who engaged him was the Tory grandee and country gentleman Bamber Gascoyne, a former lawyer and sometime member of Parliament with a reputation for speaking his mind. Though he referred to Sutton as “the pocky doctor” in letters to his friend John Strutt, Gascoyne was struck by Sutton’s understated, but confident, professional manner. He wrote to Strutt: “My children I have seen today at ye farm and there met Mr. Sutton who has been very punctual in his attendance, & if I may judge from what I have hitherto seen, is a most surprising fellow & hath a most amazing secret in giving and abating yer acrimony & venom of ye small pox.”

Though Daniel Sutton’s exceptional gift was widely acknowledged at the time he was practicing, it might be protested today that he was a mere “quack.” After all, he lived in the age of quackery, when the newspapers were full of advertisements for pills and powders for which magical powers were claimed. The Oxford Journal, in January 1766, offered “Dr. James’ Powder for fevers, the smallpox, measles, pleurisies, quincies, acute rheumatisms, colds, and all inflammatory orders, as well as those which are called, nervous, hypochondriac, and hysteric.”

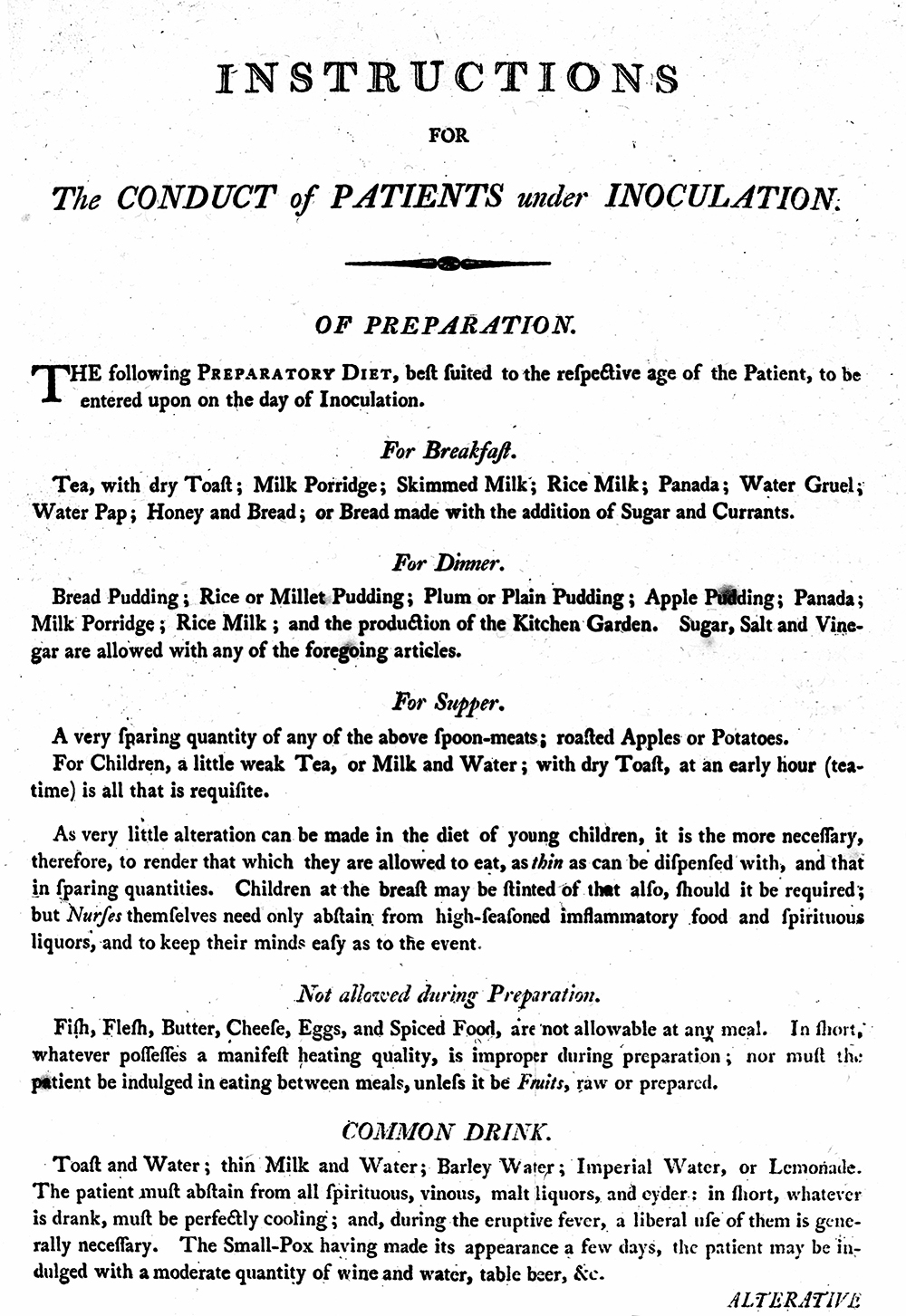

Sutton did claim to have “physic” that helped alleviate the symptoms of inoculated smallpox. And he prepared his patients with a strict diet and some laxatives. But they were not bled and there was no suggestion that his special potions “cured” smallpox. He managed the onset of the disease after inoculation with close observation, adjusting the regime to each individual. Some could return to a normal diet sooner than others. All were encouraged at some point to get out into the fresh air once the pox had appeared. This was the hallmark of Daniel Sutton’s regime, the innovation which supposedly led to the rift with his father. Nobody, including Sutton himself, could say why his regime worked. But it was impossible to deny that his was the least dangerous, least unpleasant, and most reliable approach to inoculation.

As it became more and more familiar, practiced over a large part of the country by Sutton’s approved agents, it had the effect of removing much of the fear that people had of inoculation. As Moore remarked in The History of the Small-pox, “Daniel Sutton, with his secret nostrums, propagated inoculation more in half a dozen years than both the faculties of Medicine and Surgery…had been able to do in half a century.”

Sutton was sometimes described as a quack because he had no medical qualifications. He was, in the terms of the day, a “mere empiric.” But what he achieved with his regime was real, effective as a preventive against the most devastating disease of the age.

Excerpted from The Great Inoculator: The Untold Story of Daniel Sutton and His Medical Revolution by Gavin Weightman, just published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2020 Gavin Weightman. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.