Everything that has wings is beyond the reach of the law.

—Joseph Joubert, 1791Christian Rock

Roy Moore hears a commandment.

On August 1, 2001, Roy S. Moore, chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, unveiled a 5,280-pound granite monument in the large colonnaded rotunda of the Alabama State Judicial Building in front of a large plate-glass window, with a courtyard and waterfall behind it.

The monument is in the shape of a cube, approximately three feet wide by three feet deep by four feet tall. The top is carved as two tablets with rounded tops, the common depiction of the Ten Commandments; these tablets are engraved with the Ten Commandments as excerpted from the Book of Exodus in the King James Bible and call to mind an open Bible resting on a lectern. Engraved on the left tablet is: “I am the Lord thy God”; “Thou shalt have no other Gods before me”; “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image”; “Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain”; and “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy.” Engraved on the right tablet is: “Honor thy father and thy mother”; “Thou shalt not kill”; “Thou shalt not commit adultery”; “Thou shalt not steal”; “Thou shalt not bear false witness”; and “Thou shalt not covet.” In addition, the four sides of the monument are engraved with fourteen quotations from various secular sources. The north side of the monument has a large quotation from the Declaration of Independence, “Laws of nature and of nature’s God,” and smaller quotations from George Mason, James Madison, and William Blackstone that speak of the relationship between nature’s laws and God’s laws. The large quotation on the west side of the monument is the national motto, “In God we trust”; the smaller quotations on that side were excerpted from the preamble to the Alabama Constitution and the fourth verse of the national anthem. The south side of the monument bears a large quotation from the Judiciary Act of 1789, “So help me God,” and smaller quotations from George Washington and John Jay speaking of oaths and justice. The east side of the monument has a large quotation from the Pledge of Allegiance 1954, “One nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all,” and smaller quotations from the legislative history of the pledge, James Wilson, and Thomas Jefferson suggesting that both liberty and morality are based on God’s authority.

The court visited the monument before beginning trial because all agreed that a personal on-site viewing of the monument was essential to capture fully not only the monument but its context as well. The court found the monument to be, indeed, much more than the sum of its notable quotations, large measurements, and prominent location. The court was captivated by not just the solemn ambience of the rotunda (as is often true with judicial buildings) but by something much more sublime. There was the sense of being in the presence of something not just valued and revered (such as a historical document) but also holy and sacred. Thus it was not surprising to the court that, in describing the process of designing the monument, the chief justice emphasized that the secular quotations were placed on the sides of the monument, rather than on its top, because these statements were the words of mere men and could not be placed on the same plane as the word of God. Nor was it surprising to the court that, as the evidence reflected, visitors and building employees consider the monument an appropriate, and even compelling, place for prayer. The court is impressed that the monument and its immediate surroundings are, in essence, a consecrated place, a religious sanctuary, within the walls of a courthouse.

At the monument’s unveiling ceremony, Chief Justice Moore made a speech noting that the monument depicted the “moral foundation of law.” But the chief justice made clear the monument was ultimately a monument to the giver of this moral foundation, the Judeo-Christian god and, in particular, to his sovereignty over all the affairs of men. The chief justice expressed his disagreement with those judges and other government officials who “purport that it is government and not God who gave us our rights.” He said that these officials have “turned away from those absolute standards that serve as the moral foundation of law.”

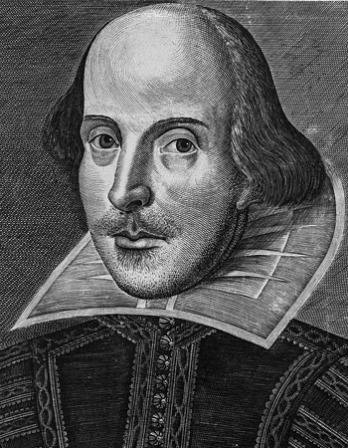

Signing of the Constitution, by Howard Chandler Christy, 1940. U.S. Capitol.

That Chief Justice Moore’s purpose in displaying the monument was nonsecular is self-evident. In his trial testimony, the chief justice gave more structure to his understanding of the relationship of God and the state, and the role the monument was intended to play in conveying that message. He explained that the Judeo-Christian god reigned over both the church and the state in this country, and that both owed allegiance to that god. In other words, the chief justice described essentially a vertical or standing triangle, with God at the top as the sovereign head, and with the state and the church side by side, forming the base under God.

The evidence in this case more than adequately reflected that the Ten Commandments have a secular aspect as well. Experts on both sides testified that the Ten Commandments were a foundation of American law, that America’s founders looked to and relied on the Ten Commandments as a source of absolute moral standards. The second tablet, of course, is entirely secular, from “Thou shalt not kill” to “Thou shalt not covet,” but the first tablet also has secular aspects. As the chief justice pointed out in his speech unveiling the monument, Samuel Adams gave a speech, the day before the signing of the Declaration of Independence, referring to the king as a false idol, alluding to the commandment that “Thou shalt have no other gods before me.”

But while the secular aspect of the Ten Commandments can be emphasized, this monument leaves no room for ambiguity about its religious appearance. The only way to miss the religious or nonsecular appearance of the monument would be to walk through the Alabama State Judicial Building with one’s eyes closed.

The court appreciates that, as a matter of conscience, one may believe that the Judeo-Christian god is sovereign over the state. In fact, the court understands that it is just this type of belief that the free-exercise clause and the establishment clause are meant to protect. Thus the court stresses that it is not disagreeing with Chief Justice Moore’s beliefs regarding the relationship of God and the state. Rather, the court disagrees with the chief justice to the extent that it understands him to be saying that, as a matter of American law, the Judeo-Christian god must be recognized as sovereign over the state, or even that the state may adopt that view. This is an opinion about the structure of American government, rather than a matter of religious conscience, that the court feels fully comfortable refusing to accept.

The court rejects the chief justice’s suggested legal understanding of the relationship between God and the state for a number of reasons. First and foremost, the chief justice’s belief that American law embraces the sovereignty of God over the state has no support in the text of the First Amendment. The First Amendment simply states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Nowhere does the Constitution or the First Amendment recognize the sovereignty of any god, Judeo-Christian or not, or describe the relationship between God and the state. In fact, this country’s founding documents support the idea that it is from the people, and not God, that the state draws its powers. The court cannot accept the chief justice’s proposed definition of the word religion, because it is, simply put, incorrect and religiously offensive. The court cannot accept a definition of religion that does not acknowledge Buddhism or Islam as a religion under the First Amendment, and would in fact directly violate Supreme Court precedent by doing so.

If all Chief Justice Moore had done were to emphasize the Ten Commandments’ historical and educational importance (for the evidence shows that they have been one of the sources of our secular laws) or their importance as a model code for good citizenship (for we all want our children to honor their parents, not to kill, not to steal, and so forth), this court would have a much different case before it. But the chief justice did not limit himself to this; he went far, far beyond. He installed a two-and-a-half-ton monument in the most prominent place in a government building, managed with dollars from all state taxpayers, with the specific purpose and effect of establishing a permanent recognition of the “sovereignty of God,” the Judeo-Christian god, over all citizens in this country, regardless of each taxpaying citizen’s individual personal beliefs or lack thereof. To this, the establishment clause says no.

If the monument is not removed within thirty days, the court will then enter an injunction requiring Justice Moore to remove it within fifteen days thereafter.

Myron H. Thompson

From his opinion in Glassroth v. Moore. Moore refused to remove the monument; he lost his appeal in 2003. Soon after, he was removed from the bench by the Alabama Court of the Judiciary for putting himself “willfully and publicly” above the law; he lost on appeal. He was elected to the bench again in 2012, then suspended in 2016 by the Court of the Judiciary for disregarding “clear federal law”; he lost on appeal. In 2017 he ran for the open U.S. Senate seat for Alabama. He lost, contested the results, and filed a complaint; it was dismissed in circuit court.