All moanday, tearsday, wailsday, thumpsday, frightday, shatterday till the fear of the Law.

—James Joyce, 1939Due Process

Lamenting the death of the rule of law in a country where it might have always been missing.

By Lewis H. Lapham

Antwerp merchant Pierre de Moucheron and his family, by an unknown artist, 1563. © Rijksmuseum.

True law is right reason in agreement with nature.

—Cicero

Law is a flag, and gold is the wind that makes it wave.

—Russian proverb

To pick up on almost any story in the news these days—political, financial, sexual, or environmental—is to be informed in the opening monologue that the rule of law is vanished from the face of the American earth. So sayeth President Donald J. Trump, eight or nine times a day to his 47 million followers on Twitter. So sayeth also the plurality of expert witnesses in the court of principled opinion (media pundit, Never Trumper, think-tank sage, hashtag inspector of souls) testifying to the sad loss of America’s democracy, a once upon a time “government of laws and not of men.”

The funeral orations make a woeful noise unto the Lord, but it’s not clear the orators know what their words mean or how reliable are their powers of observation. The American earth groans under the weight of legal bureaucracy, the body politic so judiciously enwrapped and embalmed in rules, regulations, requirements, codes, and commandments that it bears comparison to the glorified mummy of a once upon a time great king in Egypt.

Senior statesmen and tenured Harvard professors say the rule of law has been missing for three generations, ever since President Richard Nixon’s bagmen removed it from a safe at the Watergate. If so, who can be expected to know what it looks like if and when it shows up with the ambulance at the scene of a crime? Does it come dressed as a man or a woman? Blue eyes and sweet smile riding a white horse? Black uniform, steel helmet, armed with assault rifle? Or maybe the rule of law isn’t lost but misplaced. Left under a chair on Capitol Hill, in a display case at the Smithsonian, scouting locations for Clint Eastwood’s next movie.

The confusion is in keeping with the trend of the times that elected Trump to the White House. In hope of clarification, this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly looks to the lessons of history. They are more hopeful than those available to the best of my own knowledge and recollection, which tend to recognize the rule of law as the politically correct term of art for the divine right of money.

Trump won the election because he didn’t pretend otherwise. He staked his claim to the White House on the proposition that he was “really rich,” unbought and unbossed and therefore free to say and do whatever it took to Make America Great Again. A deus ex machina descending by escalator into the atrium of his eponymous tower on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue in June 2015, Trump was there to say, and say it plainly, that money is power, and power, ladies and gentlemen, is not self-sacrificing or democratic. Never was, never will be. Law unto itself, name of the game; nature of the beast.

Not the exact words in Trump’s loud and foul mouth, but the gist of the message that over the next seventeen months he shouted to camera in states red and blue. A fair enough share of his fellow citizens screamed, stamped, and voted in agreement because what he was saying they knew to be true, knew it not as precept from their study of Lenin or the catalogues of Ralph Lauren but from their downwardly mobile experience on the losing side of the class war waged over the past forty years by America’s increasingly frightened and selfish rich against its increasingly angry and dispossessed poor.

Trump didn’t need briefing papers to refine the message. He embodied it live and in person, an unscripted and overweight canary flown from its gilded cage, telling it like it is when seen from the perch of the haves looking down on the birdseed of the have-nots. Had he time or patience for looking into books instead of mirrors, he could have sourced his wisdom to Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis, who presented the case for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal: “We must make our choice. We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”

Not that it would have occurred to Trump to want both, but he might have been glad to know the Supreme Court had excused him from any further study under the heading of politics. In the world according to Trump—as it was in the worlds according to Ronald Reagan, George Bush elder and younger, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama—the concentration of wealth is the good, the true, and the beautiful. Democracy is for losers.

The framers of the Constitution were of the same opinion. The prosperous and well-educated gentlemen assembled in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 shared with John Adams the suspicion that “democracy will infallibly destroy all civilization,” agreed with James Madison that the turbulent passions of the common man lead to reckless agitation for the abolition of debts and “other wicked projects.” With Plato the framers shared the assumption that the best government, under no matter what name or flag, incorporates the means by which a privileged few arrange the distribution of property and law for the less fortunate many. They envisioned a wise and just oligarchy—to which they gave the name of a republic—managed by men like themselves, to whom Madison attributed “most wisdom to discern, and most virtue to pursue the common good of the society.” Adams thought the great functions of state should be reserved for “the rich, the wellborn, and the able”; John Jay, chief justice for the Supreme Court, observed that “those who own the country ought to govern it.”

The Trial of Constance de Beverly, by Toby Edward Rosenthal, c. 1883. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Joseph J. Szymanski in memory of Renate Lippert Szymanski (AC1993.233.1).

The framers borrowed the words for their enterprise from the English philosopher John Locke, who had declared his seventeenth-century willingness “to join in society with others who are already united, or have a mind to unite, for the mutual preservation of their lives, liberties, and estates, which I call by the general name property.” Locke could not conceive of freedom established on anything other than property. Neither could the eighteenth-century framers of America’s Constitution. By the word liberty, they meant liberty for property, not liberty for persons, and by the end of the summer of 1787 the well-to-do gentlemen in Philadelphia had drafted a document hospitable to their acquisition of more property.

But unlike our present-day makers of money and law, the founders were not stupefied plutocrats. They knew how to read and write (in Latin or French, if not also in Greek), and they weren’t consumed by an all-consuming desire for wealth. From their reading of Plutarch, they understood that oligarchy was well-advised to furnish democracy with some measure of political power because the failure to do so was likely to lead to their being roasted on pitchforks. The costs of their living they adjusted to sober and practical use in preference to gaudy self-glorifying display.

No law is sufficiently convenient to all.

—Roman proverb,Accepting of the fact that whereas democracy puts a premium on equality, a capitalist economy does not, they designed a contrivance to accommodate the motions of the heart as well the movements of a market. The Constitution joined the life of an organism with the strength of a mechanism, offering as warranty of its worth the character of men capable of caring for such a thing as a res publica, attentively benign landlords presumably relieved of the necessity to cheat and steal and lie.

The presumption in 1787 could be taken at face and fair value. The framers held their idea of law to be sacred, investing it with the intellectual idealism of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment together with the moral force of the New Testament. A marriage of faith and reason to which the young lawyer

Abraham Lincoln bore witness before the Young Men’s Lyceum in Springfield, Illinois, in 1838:

As the patriots of 1776 did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and laws, let every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor…Let reverence for the laws be breathed by every American mother to the lisping babe that prattles on her lap—let it be taught in schools, in seminaries, and in colleges…preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice. And, in short, let it become the political religion of the nation; and let the old and the young, the rich and the poor, the grave and the gay, of all sexes and tongues and colors and conditions, sacrifice unceasingly upon its altars.

Such reverence for the laws in the 1830s was lifting from the face of the American earth like a morning mist. Jefferson had noted the trend away from the idea of a republic during his two terms as president of the United States; retired from politics in 1810, he wrote from Monticello to say to a friend, “Money, and not morality, is the principle of commerce and commercial nations.” Alexis de Tocqueville, the French politician commonly regarded as the keenest observer of the early American body politic, noticed in 1831 and 1832 while traveling on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers that “in democracies, nothing is greater or more brilliant than commerce. It attracts the attention of the public and fills the imagination of the multitude.”

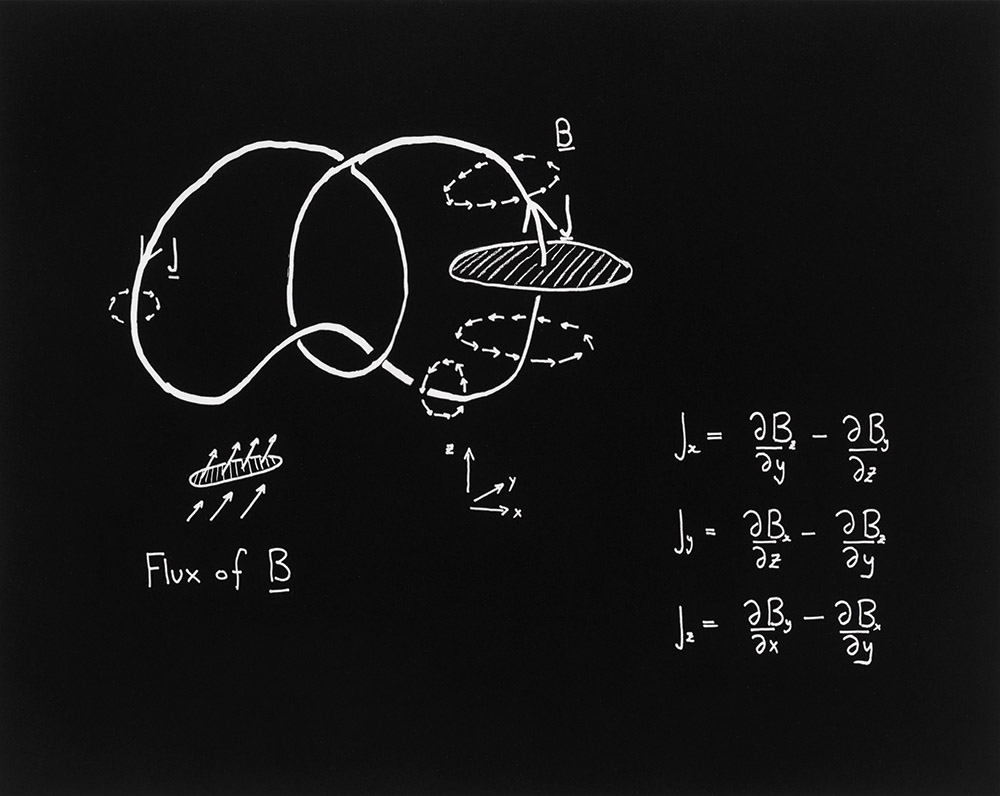

Ampère’s Law, by Simon Donaldson, 2014. © Simon Donaldson, courtesy of Nancy Hoffman Gallery.

Some historians say it was the spoils system introduced by President Andrew Jackson in the 1830s that replaced the political religion of the nation with the worship of mammon. Other historians say it was the Civil War that established the sovereignty of the almighty dollar. None of the informed sources doubt that the hope of unbought and unbossed government perished during the prolonged heyday of the late nineteenth-century Gilded Age, the phrase coined by Mark Twain to suggest that a society amounting to the sum of its vanity and greed is not a society at all, but a state of war.

President Grover Cleveland in 1887 set forth the rules of engagement with his veto of a bill passed by Congress offering financial aid to the poor. “The lesson,” said Cleveland, “should be constantly enforced that though the people support the government, the government should not support the people.” Twenty-one years later, Arthur T. Hadley, president of Yale, accepted the statement as certain truth: “The fundamental division of powers in the Constitution of the United States is between voters on the one hand and property owners on the other. The forces of democracy on one side…are set over against the forces of property on the other side.”

The law looks at no one’s face.

—Gabriel Okara, 1964Hadley in 1908 feared an imminent outbreak of hostilities, but by the time I arrived at Yale forty-four years later, all was quiet on the frontiers between labor and capital, and the instruction in what is meant in America by the rule of law was again being cribbed from Lincoln’s address to the Young Men’s Lyceum in 1838. The words had the ring of truth because in the middle years of the twentieth century, America at times showed some semblance of the republic envisioned by its eighteenth-century founders—Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, a citizen army fighting World War II, the Great Depression replaced with a prosperous and hardworking economy in which all present shared in the profits—and as a grammar school boy happily perched atop San Francisco’s Pacific Heights in the 1940s to count and identify the U.S. Navy’s ships in the bay, I rated myself present and participant in America’s triumphant emergence as the world’s supreme moral, economic, and military power in service to the common good of mankind. My grandfather was mayor of the city and therefore obliged to preside over the drafting of the United Nations charter in the San Francisco Opera House in the spring of 1945. He insisted on my being excused from school to attend the plenary sessions, there to learn at age ten, seated under crystal chandeliers, that might was right and right was might and America the face on both heads of the coin.

The teaching of American history at Yale College in the 1950s didn’t complicate the message. The Constitution and Declaration of Independence were to be admired as if carved in museum-quality marble, appreciated for their value as trust funds furnishing the heirs to America’s fortune in war (the one against the eighteenth-century British Crown) with the capital of freedom to spend wherever, whenever, and however one pleased. Nobody in blue blazer or tweed jacket characterized the res publica as living organism, mentioned any sacrifices to be made on the altar of the mind and spirit of the laws.

The various liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s produced a generation of reckless agitation against any power or authority other than its own. The voices of youth declared “Freedom Now” not only from the straitjacket of history and the tyranny of philosophies dead, white, and male but also from the bonds of family, community, gender, and church. The common ground of society meanwhile shifted, caved in, or disappeared under the pressure of ferocious and destabilizing change—social, cultural, technological, demographic, and economic—and by 1980 the only constitutional value still on the table was the one making the world safe for the acquisition of property.

Laws, like houses, lean on one another.

—Edmund Burke, 1765Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980 to restore America to its rightful place “where someone can always get rich,” his attitude and agenda not unlike Donald Trump’s, and by 1984 everywhere in the society, money was seen to be the hero with a thousand faces, greed the creative frenzy from which all blessings flow. What was billed as the Reagan Revolution and the dawn of a new Morning in America united the many and various parties of the right (conservative, neoconservative, libertarian, reactionary, evangelical, the Ku Klux Klan, and the Koch brothers) under one flag of transcendent and absolute truth—money ennobles rich people, making them healthy, wealthy, and wise; money corrupts poor people, making them lazy, ignorant, and sick. The doctrine of enlightened selfishness rebranded as neoliberalism has remained in power in Washington for the past thirty years. The separation of values treasured by a capitalist economy from those cherished by a democratic society has resulted in the accumulation of more laws limiting the freedom of persons, fewer laws restraining the license of property, the letting fall into disrepair of nearly all the infrastructure (roads, schools, rivers) that provides the citizenry with the ways and means of its common enterprise.

The framers of the Constitution didn’t transfer to money the properties of mind and spirit over which it now holds power of attorney. Doing so results in the depreciation of all values that do not pay. Absent a connection between virtue and reward, moral scruples come to be seen as unaffordable luxury. What is moral is what returns a profit to the judgment of the bottom line, and variations on the answer “Yes, but I did it for the money” satisfy all but the most tiresome objections.

Under which circumstance, as noted in this issue by

Ralph Nader, “lawlessness” becomes “an overwhelming fact of American life,” and the rule of law “little more than a torrent of dysfunctional myths.” Nader posts a list of numbers as impressive in their own right as the ones deployed by President Trump in this year’s State of the Union address to advertise America’s greatness restored: billing fraud in the health care industry amounting in 2017 to $350 billion; wage theft from low-income workers (overtime violations, minimum-wage violations, employee misclassification) $50 billion a year; according to the IRS, $450 billion a year in uncollected taxes.

Ash, by Christine Elfman, 2015. Pigment print, 40½ x 51 inches, edition of 3 plus 2 artist’s proofs. © Christine Elfman, courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

No brief list of numbers can do justice to the scale of America’s criminal enterprise, and I don’t wish to try the reader’s patience. As collected by witnesses of all colors, creeds, and sexual affiliations—by journalists, sociology professors, novelists, reformed politicians, and retired mobsters—testimony to our collective talent for the stacked deck and the fast shuffle would take up all the space on all the shelves in the Library of Congress.

Nor do I mean to suggest that every American hot-dog salesman and tech entrepreneur, doctor, senator, arms dealer, tinker, tailor, soldier, spy is a criminal. The proposition fortunately is absurd. If it were true, the nation would cease to exist, wrecked by the stupidity of the belief that the future is a product to be bought instead of a fortune to be told.

But that is the stupidity currently in office in Washington, most obviously in the person and preaching of President Trump but also in the noisy dysfunction of Congress. Madison expected legislators to dominate the work of government, Congress to be “everywhere extending the sphere of its activity and drawing all power into its impetuous vortex.” Neither the noun nor the adjective describe the current proceedings on Capitol Hill. The congressional sphere of activity has been reduced over the past thirty years to the striking of poses in the face of a fun-house mirror, the exercise of power handed off to the president, the public-opinion polls, and the courts.

Our elected representatives in Washington don’t know how to do or make law, can’t write it or read it, don’t know what it looks like until it shows up at a picnic wearing a hat or a dress paid for by JPMorgan Chase, Monsanto, Anheuser-Busch InBev, or Boeing. Few members of the House and the Senate read the paperwork they sign into law, much of it composed by lobbyists in whose interest the wording is procured. The honorable ladies and gentlemen on both sides of the aisle spend virtually no time in the building. They don’t debate; they deliver favors to patrons, clients, and friends, route insults to enemies real and imagined, attend photo opportunities to promote their money and vote-getting smiles.

A functioning police state needs no police.

—William S. Burroughs, 1959The work of government meanwhile gets left to what the lawyer and legal thinker Philip K. Howard defines as the rule of nobody, his term for the mindless bureaucracies (municipal, state, and federal) that litter the face of the American earth with hundreds of millions of rules and regulations to control the conduct and deportment of the nation’s roads, rivers, schools, factories, shopping malls, markets, hospitals, playgrounds, and personal behaviors; tell us how, when, and with whom to tote the barge and lift the bale, sing the national anthem or the blues. Rules so elaborately complicated and detailed cannot be understood or obeyed; whether asleep or awake, seated at the low or high end of the table, the entire population is found guilty of involuntary noncompliance. Madison, writing The Federalist, foresaw the stupidity in 1788: “It will be of little avail to the people…if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood.”

Of little avail because automatic government made by, with, and for the wholesome, clean-living machinery of dehumanized bureaucracy can suffer fools but not a cost-benefit analysis. To eliminate the possibility of human error, perversity, and prejudice is also to delete the freedoms of human feeling, imagination, and thought, lose all sense of the law as a living organism fit to the needs and predicament of human beings.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. argues the point of order in his essay “The Path of the Law”:

The development of our law has gone on for nearly a thousand years, like the development of a plant, each generation taking the inevitable next step, mind, like matter, simply obeying a law of spontaneous growth.

Holmes goes on to say that “the rational study of law is still to a large extent the study of history,” its ways, means, and ends stated or ready to be stated in words. Which is the hope and intention undertaken in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly. To give up the idea of history as straitjacket, reperceive it as life preserver.

Click here for an audio version of this essay.