Everybody says it; and what everybody says must be true.

—James Fenimore Cooper, 1844Biding Time

Balzac stages an intervention.

Mme de Langeais sent her carriage and liveried servants to wait at the Marquis de Montriveau’s door from eight o’clock in the morning till three in the afternoon. Armand lived on the rue de Tournon, a few steps away from the Chamber of Peers, and that very day the House was sitting; but long before the peers returned to their palaces, several people had recognized the duchess’ carriage and liveries.

In a moment the news was spread with telegraphic speed through all the coteries in the Faubourg Saint-Germain; it reached the Tuileries and the Élysée Bourbon; it was the sensation of the day, the matter of all the talk from noon till night. Almost everywhere the women denied the facts, but in such a manner that the report was confirmed; the men one and all believed it and manifested a most indulgent interest in Mme de Langeais.

While the chateau, the faubourg, and the Chaussee d’Antin were discussing the shipwreck of aristocratic virtue; while excited young men rushed about on horseback to make sure that the carriage was standing in the rue de Tournon, and the duchess in consequence was beyond a doubt in M. de Montriveau’s rooms, Mme de Langeais, with heavy throbbing pulses, was lying hidden away in her boudoir. The elder members of Mme de Langeais’ family were engaged in calling upon one another, arranging to read her a homily and to hold a consultation as to the best way of putting a stop to the scandal.

At three o’clock, therefore, M. le Duc de Navarreins, the Vidame de Pamiers, the old Princesse de Blamont-Chauvry, and the Duc de Grandlieu were assembled in Mme la Duchesse de Langeais’ drawing room. To them, as to all curious inquirers, the servants said that their mistress was not at home; the duchess had made no exceptions to her orders.

“I still refuse to believe that she can have gone to M. de Montriveau,” said the Duc de Navarreins.

“Bah!” returned the princess.

“What is to be done?” asked the duke.

“If my dear niece is wise,” said the princess, “she will go to court this evening. Fortunately, today is Monday, and reception day—and you must see that we all rally around her and give the lie to this absurd rumor. There are hundreds of ways of explaining things. And if the Marquis de Montriveau is a gentleman, he will come to our assistance. We will bring these children to listen to reason—”

Just at that moment the duchess came out of her boudoir. She had recognized her aunt’s voice and heard the name of Montriveau. She was still in her loose morning gown; and even as she came in, M. de Grandlieu, looking carelessly out of the window, saw his niece’s carriage driving back along the street. The duke took his daughter’s face in both hands and kissed her on the forehead.

“So, dear girl,” he said, “you do not know what is going on?”

“Has anything extraordinary happened, father dear?”

“Why, all Paris believes that you are with M. de Montriveau.”

“My dear Antoinette, you were at home all the time, were you not?” said the princess, holding out a hand, which the duchess kissed with affectionate respect.

“Yes, dear aunt. I was at home all the time. And,” she added, as she turned to greet the Vidame and the Marquis, “I wished that all Paris should think that I was with M. de Montriveau.”

The duke flung up his hands, struck them together in despair, and folded his arms.

“Then cannot you see what will come of this mad freak?” he asked at last.

But the aged princess had suddenly risen, and stood looking steadily at the duchess; the younger woman flushed, and her eyes fell. Mme de Chauvry gently drew her closer, and said, “My little angel, let me kiss you!”

She kissed her niece very affectionately on the forehead, and continued smiling, while she held her hand in a tight clasp. “We are not under the Valois now, dear child. You have compromised your husband and your position. Still, we will arrange to make everything right.”

“But, dear aunt, I do not wish to make it right at all. It is my wish that all Paris should say that I was with M. de Montriveau this morning. If you destroy that belief, however ill grounded it may be, you will do me a singular disservice.”

“Do you really wish to ruin yourself, child, and to grieve your family?”

“My family, dear father, unintentionally condemned me to irreparable misfortune when they sacrificed me to family considerations. You may perhaps blame me for seeking alleviations, but you will certainly feel for me.”

The princess beckoned her niece to a little low chair by her side so that the two could speak alone.

Northern League leader Umberto Bossi smoking in his car, Pavia, Italy, 2006. Photograph by Pier Marco Tacca. © Pier Marco Tacca / Getty Images.

“My pearl,” said she, “in this world below, I know nothing worse calumniated than God and the eighteenth century. For as I look back over my own young days, I do not recollect that a single duchess trampled the proprieties underfoot as you have just done. Novelists and scribblers brought the reign of Louis XV into disrepute. Do not believe them. The Du Barry, my dear, was quite as good as the widow Scarron, and the more agreeable woman of the two. In my time a woman could keep her dignity among her gallantries. Indiscretion was the ruin of us, and the beginning of all the mischief. The philosophists—the nobodies we admitted into our salons—had no more gratitude or sense of decency than to make an inventory of our hearts, to traduce us one and all, and to rail against the age by way of a return for our kindness. The people are not in a position to judge of anything whatsoever; they looked at the facts, not at the form. But the men and women of those times, my heart, were quite as remarkable as at any other period of the monarchy. Not one of your Werthers, none of your notabilities, as they are called, never a one of your men in yellow kid gloves and trousers that disguise the poverty of their legs, would cross Europe in the dress of a traveling hawker to brave the daggers of a Duke of Modena, and to shut himself up in the dressing room of the regent’s daughter at the risk of his life. Not one of your little consumptive patients with their tortoiseshell eyeglasses would hide himself in a closet for six weeks, like Lauzun, to keep up his mistress’ courage while she was lying in of her child. There was more passion in M. de Jaucourt’s little finger than in your whole race of higglers that leave a woman to better themselves elsewhere. Just tell me where to find the page that would be cut in pieces and buried under the floorboards for one kiss on the Königsmark’s gloved finger!

“Really it would seem today that the roles are exchanged, and women are expected to show their devotion for men. These modern gentlemen are worth less, and think more of themselves. Believe me, my dear, all these adventures that have been made public, and now are turned against our good Louis XV, were kept quite secret at first. If it had not been for a pack of poetasters, scribblers, and moralists, who hung about our waiting-women and took down their slanders, our epoch would have appeared in literature as a well-conducted age. I am justifying the century and not its fringe. Perhaps a hundred women of quality were lost. But for every one, the rogues set down ten, like the gazettes after a battle when they count up the losses of the beaten side. And in any case, I do not know that the revolution and the empire can reproach us; they were coarse, dull, licentious times. Faugh! It is revolting. Those are the brothels of French history.

“This preamble, my dear child,” she continued after a pause, “brings me to the thing that I have to say. If you care for Montriveau, you are quite at liberty to love him at your ease, and as much as you can. I know by experience that unless you are locked up (but locking people up is out of fashion now), you will do as you please; I should have done the same at your age. Only, sweetheart, I should not have given up my right to be the mother of future Ducs de Langeais. So mind appearances. No man is worth a single one of the sacrifices we are foolish enough to make for their love. Put yourself in such a position that you may still be M. de Langeais’ wife, in case you should have the misfortune to repent. When you are an old woman, you will be very glad to hear mass said at court, and not in some provincial convent. Therein lies the whole question. A single imprudence means an allowance and a wandering life. It means that you are at the mercy of your lover. It means that you must put up with insolence from women who are not so honest, precisely because they have been very vulgarly sharp-witted. It would be a hundred times better to go to Montriveau’s at night in a cab, and disguised, instead of sending your carriage in broad daylight. You are a little fool, my dear child! Your carriage flattered his vanity; your person would have ensnared his heart. All this that I have said is just and true. But for my own part, I do not blame you. You are two centuries behind the times with your false ideas of greatness. There, leave us to arrange your affairs, and say that Montriveau made your servants drunk to gratify his vanity and to compromise you—”

The duchess rose to her feet with a spring. “In heaven’s name, Aunt, do not slander him!”

The old princess’ eyes flashed.

“Dear child,” she said, “I should have liked to spare such of your illusions as were not fatal. But there must be an end of all illusions now. You would soften me if I were not so old. Come, now, do not vex him, or us, or anyone else. I will undertake to satisfy everybody; but promise me not to permit yourself a single step henceforth until you have consulted me. Tell me all, and perhaps I may bring it all right again.”

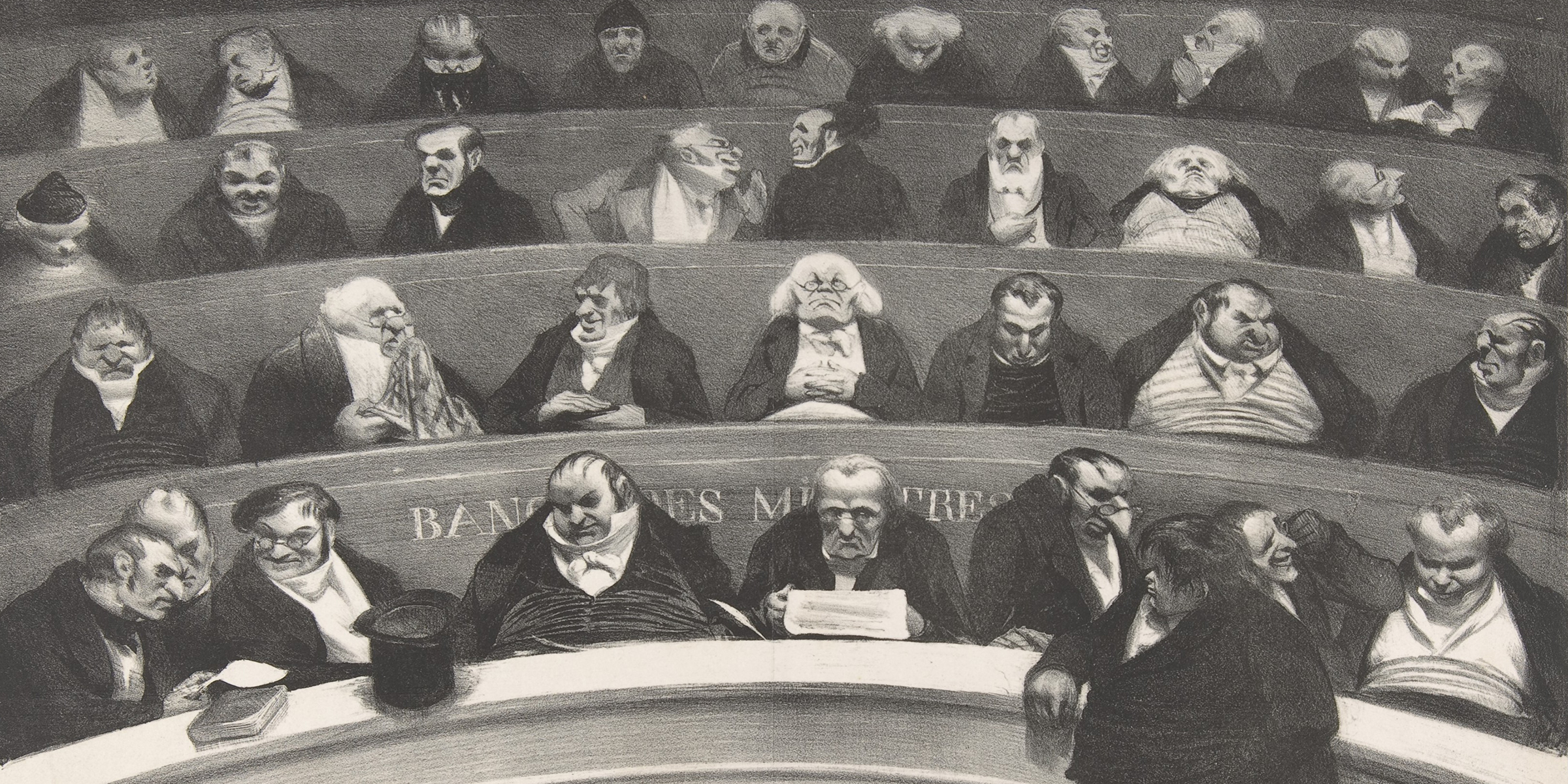

The Legislative Belly (detail), by Honoré Daumier, 1834. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Edwin De T. Bechtel, 1957.

“Aunt, I promise—”

“To tell me everything?”

“Yes, everything. Everything that can be told.”

“But, my sweetheart, it is precisely what cannot be told that I want to know. Let us understand each other thoroughly. Come, let me put my withered old lips on your beautiful forehead. No; let me do as I wish. I forbid you to kiss my bones. Old people have a courtesy of their own…There, take me down to my carriage,” she added, when she had kissed her niece.

“Then may I go to him in disguise, dear aunt?”

“Why—yes. The story can always be denied,” said the old princess.

This was the one idea that the duchess had clearly grasped in the sermon. When Mme de Chauvry was seated in the corner of her carriage, Mme de Langeais bade her a graceful adieu and went up to her room. She was quite happy again.

“My person would have snared his heart. My aunt is right—a man cannot surely refuse a pretty woman when she understands how to offer herself.”

That evening, at the Élysée Bourbon, the Duc de Navarreins, M. de Pamiers, M. de Marsay, M. de Grandlieu, and the Duc de Maufrigneuse triumphantly refuted the scandals that were circulating with regard to the Duchess de Langeais. So many officers and other persons had seen Montriveau walking in the Tuileries that morning that the silly story was set down to chance, which takes all that is offered. And so in spite of the fact that the duchess’ carriage had waited before Montriveau’s door, her character became as clear and as spotless as Mambrino’s sword after Sancho had polished it up.

Honoré de Balzac

From The Duchesse de Langeais. This novel, part of Balzac’s History of the Thirteen trilogy, details the plight of a young aristocratic woman in Restoration Paris. The duchess, whose husband lives a military life apart from her, falls in love with the war hero Armand de Montriveau. “We are not talking of troubling your felicity,” says her aunt elsewhere in this novel, “but of reconciling it with social usages. We all of us here assembled know that marriage is a defective institution tempered by love. But when you take a lover, is there any need to make your bed in the Place du Carrousel?”