It is He who has subdued the ocean so that you may eat of its fresh fish and bring up from its depth ornaments to wear. Behold the ships plowing their course through it. All this, that you may seek His bounty and render thanks.

—The Qur’an, 625Taking Stock

A slave smuggler’s journal.

The dismal records of a voyage I made from Rio Basso to the Floridas as entered in my journal:

October 28

Left Rio Basso this day in the Boa Morte, formerly an American trader, now owned by Don Ricardo Villeno, my respectable uncle. She is commanded by a creole of Santo Domingo, Pierre Leclerc, and bound for Pensacola, in the Floridas, with a cargo of nine hundred slaves. Monsieur Leclerc is a peppery little fellow, an old slaver, and has an interest in the freight. The second officer is Diego Ramos, a Portuguese from Fayal, and we three were in the roundhouse, as every inch of space is occupied by the blacks, cabin and hold knocked into slave decks, and packed tight at that. The stock is healthy, however, and we look for a profitable trip.

October 30

Leclerc is reckoning up his anticipated profits, and I may as well do the same. I have one hundred prime blacks—only twenty females—all branded, in good Spanish, with my name, felippe drax, and I begin to feel the anxieties of a property owner. My little venture, at present prices, ought to bring me eight thousand dollars—a tolerable setup, with a little stock left on hand at Rio Basso. I shall invest in profitable goods, as my uncle advises, and go back prepared to begin trade for my own profit.

November 1

Everything prosperous, only three sick cases, low fever. Quinine will make them all right, though the sharks are following us as if they smell sickness. Leclerc and I have had a chat today about this African business. He says he’s repugnant to it, and I confess it’s not a thing I like. But, as my uncle argues, slaves must be bought and sold; somebody must do the trading, and why not make hay while the sun shines?

Underwater Garden, by Didier Massard, 2005. © Didier Massard, courtesy the artist and Julie Saul Gallery.

November 2

Pedro, my assistant, reports one of our patients blind. We had half the gangs on deck today for exercise; they danced and sang, under the driver’s whip, but are far from sprightly. Captain Leclerc says he never knew such a sluggish set, yet they all appear healthy.

November 3

Bad news. We have ophthalmia among the slaves, decidedly, and spreading. Eight are reported as blind.

November 4

Captain Leclerc is sick, confined to his berth. The ophthalmia is spreading among the blacks. I have nineteen on deck, under treatment.

November 7

My God! That scourge of destruction, the smallpox, has broken out. Leclerc is down with it, and two of the crew, and I fear it is among the slaves. We are threatened with foul weather.

November 14

I make another entry in my journal. God knows whether I shall ever reach port alive. The Boa Morte is well named. It is a death ship, and has been feeding the sharks with corpses for seven days past. I have not slept a dozen hours during the week, and it is now Sunday evening, and a fit Sabbath day for a slaver, perhaps. Death and despair on every side. Last Tuesday the smallpox began to rage, and we hauled sixty corpses out of the hold. Diego Ramos can hardly control the crew, and we have to rely on gangs of slaves to drag the dead heaps from among the living. Captain Leclerc is out of danger, but remains blind with ophthalmia. God help us all, if this goes on.

November 15

I have got through another day and night, and am yet alive. Diego Ramos and a half-dozen sailors are all of the crew to be relied on. We stimulate the blacks with rum in order to get their help in removing corpses; thirty Negroes and two Portuguese sailors were thrown overboard today. I have been among the blacks in a reckless way, under the artificial excitement of laudanum and liquor, and the sights I witnessed; may I never look on such again. This is a dreadful trade. Leclerc says it sometimes drives men crazy, and I think it is no wonder. A few days more of this infernal pest ship will make me insane, I really believe. Diego Ramos says that if we had known it in time, we might have saved our cargo by poisoning the first cases, but who could foresee its spread in this manner. Some of the blacks are raving mad and screech like wild beasts. Diego Ramos says we might close the hatches and suffocate all below, as a last resort, but Captain Leclerc will not hear of that alternative. Besides, we have near seven hundred still, and may save half. And my venture is among the saved ones as yet; not one of my band has gone overboard, so Diego says. Lucky, but will it be so long?

November 16

The Boa Morte is a floating hell. Our drunken Negroes almost command the ship. Diego Ramos was obliged to shoot one today, or the fellow might have strangled him. Never can such scenes be imagined as we witness every day. I wonder how Diego can keep so cool; I wonder that I am not sick, blind, or crazy with the rest. Captain Leclerc, I believe, is dying. He is sleeping now, while I am writing, and his face is like a sheet in whiteness. He asked me to read a chapter in his French Gospel today.

November 17

We have had a violent storm, and the hatches are closed. The work of death goes on unseen. Captain Leclerc is better today and begins to see a little. God grant he may recover! Diego Ramos is still well, and so am I, after all we have gone through—but what would tempt me to pass such another ten days as the last? Not all the wealth of the Indies! Leclerc is quite serious and intends to abandon the slave traffic. He said today he thought it an accursed thing; I told Diego Ramos, and he laughed, remarking that the “devil was sick, and wanted to turn monk.” I feel scruples myself about this matter, in spite of Diego’s ridicule. If I get my eight thousand dollars for the slaves—should they survive—I am inclined to invest it in some other business in a more civilized way. It is a horrible night, the lightning glaring, the wind roaring, and the ship tossing. I think Captain Leclerc is right. I hope I shall never be so hardened as Ramos. That fellow would laugh at the gallows.

On the Beach, Boulogne-sur-Mer, by Édouard Manet, c. 1869. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon.

November 19

Thanks be to God! We are alive, on a steady sea, after experiencing a most frightful hurricane. Yesterday even Diego Ramos thought we were lost. The sun went down red, as the previous night, and Diego prophesied a continuance of the tempest, which before terrified us. The wind shifted to the west, the sky grew black as ink and was filled with fiery appearances. The thunder roared and lightning flashed incessantly. Our ship was whirled about like a top and driven before the gale nearly all night, without a rag of canvas. We heard guns during the storm but have seen no sail, though we are approaching the Gulf of Mexico today. Captain Leclerc is on deck, very feeble, but able to see once more. Diego Ramos advises not to open the hatches, till we reach port, which we hope to do by sunset, if the wind continues fair.

November 20

Anchored last night in Pensacola Bay, where the voyage of the Boa Morte terminated, after we had landed our surviving Negroes on one of the shallow beaches near the mouth of the Escambia River. Here, with the assistance of laborers from the neighboring town, we rigged sheds for our sick and took measures for lime-washing and fumigating the ship. Strange as it may seem, we saved 519 out of our nine hundred, and much to my satisfaction, sixty-four of these had my brand, so that I was not such a loser as I expected to be.

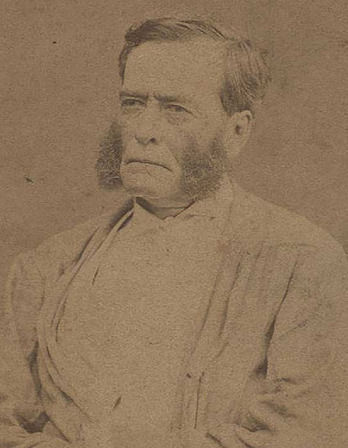

Philip Drake

Some factual aspects of Philip Drake’s memoir, Revelations of a Slave Smuggler, have been questioned, but he claimed that for nearly fifty years he facilitated the transportation and importation of African slaves to, among other places, Brazil, Cuba, and the United States. The U.S. Constitution, in Article I, Section 9, stipulates that Congress could not outlaw the foreign slave trade before 1808. In that year the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves took effect. It was not always rigorously enforced.