“I will not stay in Lowell any longer. I am determined to give my notice this very day,” said Ellen Collins, as the earliest bell was tolling to remind us of the hour for labor.

“Why, what is the matter, Ellen? It seems to me you have dreamed out a new idea! Where do you think of going? And what for?”

“I am going home, where I shall not be obliged to rise so early in the morning, nor be dragged about by the ringing of a bell, nor confined in a close noisy room from morning till night. I will not stay here. I am determined to go home in a fortnight.”

“And so, Ellen,” said I, “you think it unpleasant to rise so early in the morning and be confined in the noisy mill so many hours during the day. And I think so, too. All this, and much more, is very annoying, no doubt. But we must not forget that there are advantages as well as disadvantages in this employment, as in every other. If we expect to find all sunshine and flowers in any station in life, we shall most surely be disappointed. We are very busily engaged during the day, but then we have the evening to ourselves, with no one to dictate to or control us. I have frequently heard you say that you would not be confined to household duties, and that you disliked the millinery business altogether, because you could not have your evenings for leisure. You know that in Lowell, we have schools, lectures, and meetings of every description, for moral and intellectual improvement. I believe there is no place where there are so many advantages within the reach of the laboring class of people as exist here, where there is so much equality, so few aristocratic distinctions, and such good fellowship as may be found in this community. A person has only to be honest, industrious, and moral to secure the respect of the virtuous and good, though he may not be worth a dollar, while on the other hand, an immoral person, though he should possess wealth, is not respected.”

“As to the morality of the place,” returned Ellen, “I have no fault to find. I object to the constant hurry of everything. We cannot have time to eat, drink, or sleep. We have only thirty minutes, or at most three-quarters of an hour, allowed us to go from our work, partake of our food, and return to the noisy clatter of machinery. Up before day, at the clang of the bell—and out of the mill by the clang of the bell—into the mill, and at work, in obedience to that ding-dong of a bell—just as though we were so many living machines. I will give my notice tomorrow.”

“Ellen,” said I, “do you remember what is said of the bee, that it gathers honey even in a poisonous flower? May we not in like manner, if our hearts are rightly attuned, find many pleasures connected with our employment? Why is it, then, that you so obstinately look altogether on the dark side of a factory life? I think you thought differently while you were at home, on a visit, last summer—for you were glad to come back to the mill in less than four weeks. Tell me, now—why were you so glad to return to the ringing of the bell, the clatter of the machinery, the early rising, the half-hour dinner, and so on?”

I saw that my discontented friend was not in a humor to give me an answer—and I therefore went on with my talk.

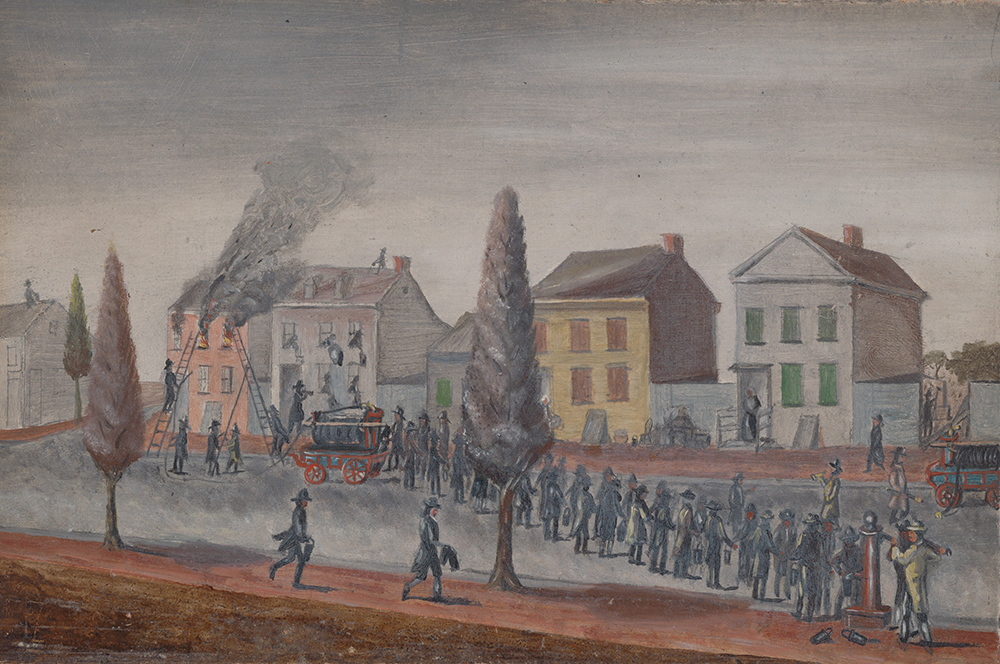

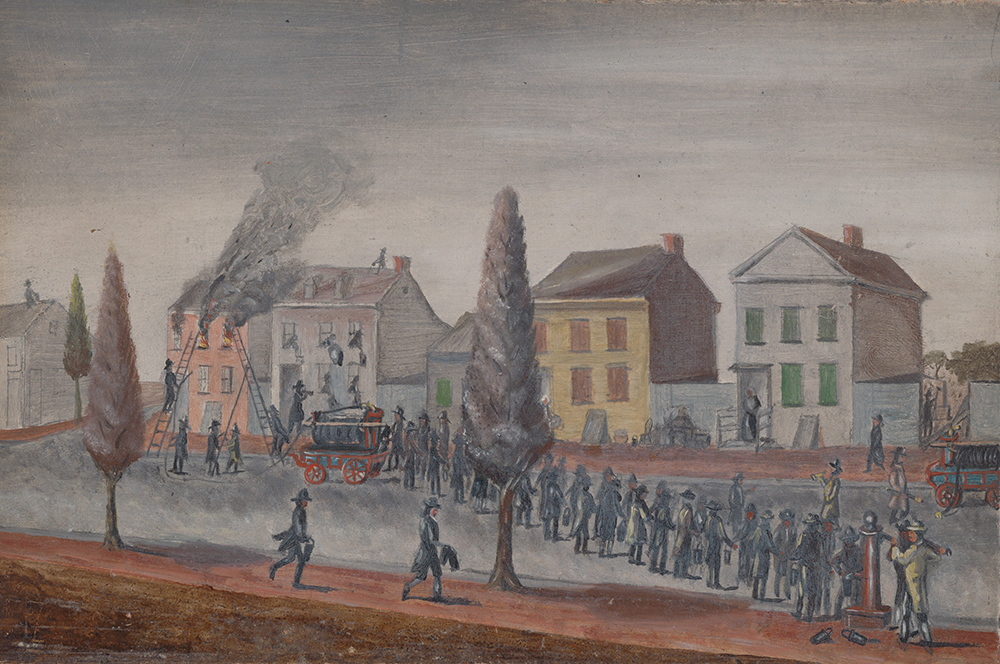

Fighting a Fire, by William P. Chappel, c. 1875. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Edward W.C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps, and Pictures, bequest of Edward W.C. Arnold, 1954.

“You are fully aware, Ellen, that a country life does not exclude people from labor—to say nothing of the inferior privileges of attending public worship—that people have often to go a distance to meeting of any kind, that books cannot be so easily obtained as they can here, that you cannot always have just such society as you wish, that you…”

She interrupted me by saying, “We have no bell, with its everlasting ding-dong.”

“What difference does it make?” said I, “whether you shall be awakened by a bell or the noisy bustle of a farmhouse? For, you know, farmers are generally up as early in the morning as we are obliged to rise.”

“But then,” said Ellen, “country people have none of the clattering of machinery constantly dinning in their ears.”

“True,” I replied, “but they have what is worse—and that is a dull, lifeless silence all around them. The hens may cackle sometimes, and the geese gabble, and the pigs squeal…”

Ellen’s hearty laugh interrupted my description, and presently we proceeded, very pleasantly, to compare a country life with a factory life in Lowell. Her scowl of discontent had departed, and she was prepared to consider the subject candidly. We agreed that since we must work for a living, the mill, all things considered, is the most pleasant.

Almira, from “The Spirit of Discontent.” Beginning in the 1830s, thousands of “mill girls”—young women mostly from nearby farm communities—drawn by the highest wages in the country offered to female workers, took up employment at the textile mills of Lowell, Massachusetts. Their newfound independence led to the formation of “improvement circles” and the founding of a literary magazine, The Lowell Offering, in which this pseudonymous sketch appeared. Though to what extent management held editorial sway over the journal is debated, one scholar noted that it “provided a fortuitous medium for those two expressions of distinctly American genius: public relations and packaging.”

Back to Issue