’Tis the sport to have the engineer / Hoist with his own petard.

—William Shakespeare, 1600Bureaucratic Drift

Jonathan Swift visits Laputa’s works in progress.

After having seen all the curiosities of the island of Laputa, I was very desirous to leave it, being heartily weary of those people. They were indeed excellent in two sciences, mathematics and music, for which I have great esteem and wherein I am not unversed, but at the same time so abstracted and involved in speculation that I never met with such disagreeable companions.

On the sixteenth day of February, I took leave of his majesty and the court. The king made me a present to the value of about two hundred pounds English, together with a letter of recommendation to a friend of his in Lagado, the metropolis. The island being then hovering over a mountain about two miles from it, I was let down from the lowest gallery in the same manner as I had been taken up.

The continent, as far as it is subject to the monarch of the flying island, passes under the general name of Balnibarbi, and the metropolis is called Lagado. I felt some little satisfaction in finding myself on firm ground. I walked to the city without any concern, being clad like one of the natives and sufficiently instructed to converse with them. I soon found out the person’s house to whom I was recommended, presented my letter from his friend the grandee in the island, and was received with much kindness. This great lord, whose name was Munodi, ordered me an apartment in his own house, where I continued during my stay and was entertained in a most hospitable manner.

The next morning after my arrival, he took me in his chariot to see the town, which is about half the bigness of London, but the houses very strangely built, and most of them out of repair. The people in the streets walked fast, looked wild, their eyes fixed, and were generally in rags. We passed through one of the town gates and went about three miles into the country, where I saw many laborers working with several sorts of tools in the ground but was not able to conjecture what they were about; neither did I observe any expectation either of corn or grass, although the soil appeared to be excellent. I could not forbear admiring these odd appearances, both in town and country, and I made bold to desire my conductor that he would be pleased to explain to me what could be meant by so many busy heads, hands, and faces, both in the streets and the fields, because I did not discover any good effects they produced, but on the contrary, I never knew a soil so unhappily cultivated, houses so ill-contrived and so ruinous, or a people whose countenances and habit expressed so much misery and want.

This lord Munodi was a person of the first rank and had been some years governor of Lagado but, by a cabal of ministers, was discharged for insufficiency. However, the king treated him with tenderness, as a well-meaning man, but of a low, contemptible understanding.

When I gave that free censure of the country and its inhabitants, he told me with a very melancholy air “that about forty years ago, certain persons went up to Laputa, either upon business or diversion and, after five months’ continuance, came back with a very little smattering in mathematics, but full of volatile spirits acquired in that airy region; that these persons, upon their return, began to dislike the management of everything below and fell into schemes of putting all arts, sciences, languages, and mechanics upon a new foot. To this end, they procured a royal patent for erecting an academy of projectors in Lagado, and the humor prevailed so strongly among the people that there is not a town of any consequence in the kingdom without such an academy. In these colleges the professors contrive new rules and methods of agriculture and building, and new instruments and tools for all trades and manufactures, whereby, as they undertake, one man shall do the work of ten, a palace may be built in a week, of materials so durable as to last forever without repairing. All the fruits of the earth shall come to maturity at whatever season we think fit to choose and increase a hundredfold more than they do at present, with innumerable other happy proposals. The only inconvenience is that none of these projects are yet brought to perfection, and in the meantime, the whole country lies miserably waste, the houses in ruins, and the people without food or clothes. By all which, instead of being discouraged, they are fifty times more violently bent upon prosecuting their schemes, driven equally on by hope and despair; that as for himself, being not of an enterprising spirit, he was content to go on in the old forms, to live in the houses his ancestors had built, and act as they did, in every part of life, without innovation; that some few other persons of quality and gentry had done the same but were looked on with an eye of contempt and ill will, as enemies to art, ignorant, and ill commonwealth’s-men, preferring their own ease and sloth before the general improvement of their country.”

His lordship added that he would not, by any further particulars, prevent the pleasure I should certainly take in viewing the grand academy, whither he was resolved I should go.

This academy is not an entire single building but a continuation of several houses on both sides of a street which, growing waste, was purchased and applied to that use. I was received very kindly by the warden and went for many days to the academy. Every room has in it one or more projectors, and I believe I could not be in fewer than five hundred rooms.

The first man I saw was of a meager aspect, with sooty hands and face, his hair and beard long, ragged, and singed in several places. His clothes, shirt, and skin were all of the same color. He had been eight years upon a project for extracting sunbeams out of cucumbers, which were to be put in vials hermetically sealed and let out to warm the air in raw inclement summers. He told me, he did not doubt, that in eight years more, he should be able to supply the governor’s gardens with sunshine at a reasonable rate, but he complained that his stock was low and entreated me “to give him something as an encouragement to ingenuity, especially since this had been a very dear season for cucumbers.” I made him a small present, for my lord had furnished me with money on purpose, because he knew their practice of begging from all who go to see them.

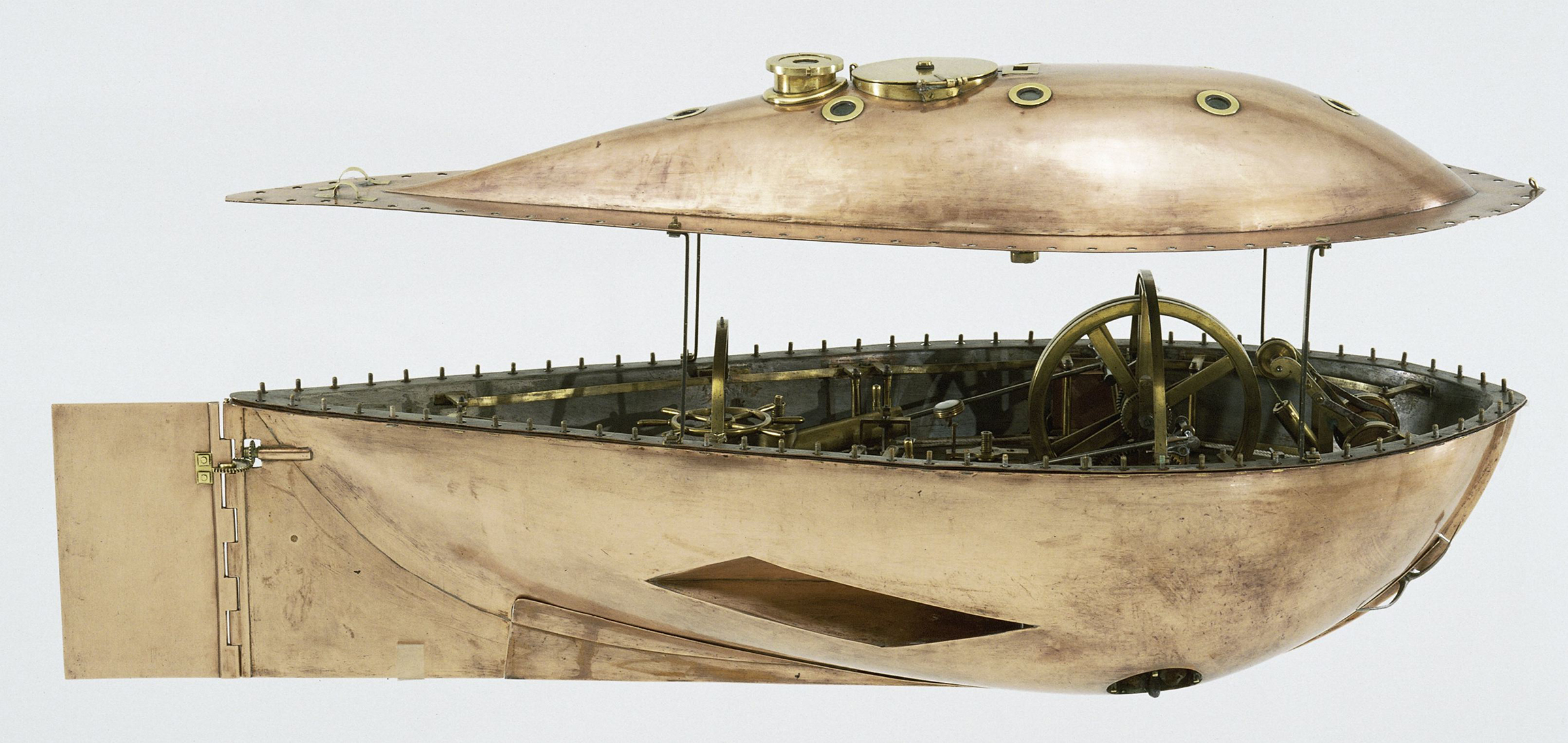

Copper model of a submarine, by Antoine Lipkens and Olke Uhlenbeck, 1836–39. Rijksmuseum.

I went into another chamber but was ready to hasten back, being almost overcome with a horrible stink. My conductor pressed me forward, conjuring me in a whisper “to give no offense, which would be highly resented,” and therefore I dared not so much as stop my nose. The projector of this cell was the most ancient student of the academy. His face and beard were of a pale yellow, his hands and clothes daubed over with filth. When I was presented to him, he gave me a close embrace, a compliment I could well have excused. His employment, from his first coming into the academy, was an operation to reduce human excrement to its original food, by separating the several parts, removing the tincture which it receives from the gall, making the odor exhale, and scumming off the saliva. He had a weekly allowance, from the society, of a vessel filled with human ordure about the bigness of a Bristol barrel.

I saw another at work to calcine ice into gunpowder, who likewise showed me a treatise he had written concerning the malleability of fire, which he intended to publish.

There was a most ingenious architect, who had contrived a new method for building houses, by beginning at the roof and working downward to the foundation, which he justified to me by the like practice of those two prudent insects, the bee and the spider.

In another apartment, I was highly pleased with a projector who had found a device of plowing the ground with hogs, to save the charges of plows, cattle, and labor. The method is this: in an acre of ground you bury, at six inches distance and eight deep, a quantity of acorns, dates, chestnuts, and other mast or vegetables, whereof these animals are fondest. Then you drive six hundred or more of them into the field, where in a few days they will root up the whole ground in search of their food and make it fit for sowing, at the same time manuring it with their dung. It is true, upon experiment, they found the charge and trouble very great, and they had little or no crop. However, it is not doubted that this invention may be capable of great improvement.

I visited many other apartments but shall not trouble my reader with all the curiosities I observed, being studious of brevity.

Jonathan Swift

From Gulliver’s Travels. Together with Alexander Pope, John Gay, Thomas Parnell, and John Arbuthnot, Swift founded the Scriblerus Club in 1713. Their principal project was the invention of the satirical character Martinus Scriblerus, whose cowritten “memoirs” poked fun at contemporary literature and scholarship. “The chief end I propose to myself in all my labors is to vex the world rather than divert it,” Swift wrote to Pope in 1725, shortly after completing Gulliver’s Travels. “From the highest to the lowest, it is universally read,” Gay wrote shortly after its publication, “from the cabinet council to the nursery.”