Those who view mathematical science not merely as a vast body of abstract and immutable truths, whose intrinsic beauty, symmetry, and logical completeness, when regarded in their connection together as a whole, entitle them to a prominent place in the interest of all profound and logical minds, but as possessing a yet deeper interest for the human race when it is remembered that this science constitutes the language through which alone we can adequately express the great facts of the natural world, and those unceasing changes of mutual relationship which, visibly or invisibly, consciously or unconsciously to our immediate physical perceptions, are interminably going on in the agencies of the creation we live amid: those who thus link on mathematical truth as the instrument through which the weak mind of man can most effectually read his Creator’s works will regard with especial interest all that can tend to facilitate the translation of its principles into explicit practical forms.

The distinctive characteristic of the Analytical Engine, and that which has rendered it possible to endow mechanism with such extensive faculties as bid fair to make this engine the executive right hand of abstract algebra, is the introduction into it of the principle which Joseph-Marie Jacquard devised for regulating, by means of punched cards, the most complicated patterns in the fabrication of brocaded stuffs. We may say most aptly that the Analytical Engine weaves algebraical patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.

The Analytical Engine does not occupy common ground with mere “calculating machines.” It holds a position wholly its own; and the considerations it suggests are most interesting in their nature. In enabling mechanism to combine together general symbols in successions of unlimited variety and extent, a uniting link is established between the operations of matter and the abstract mental processes of the most abstract branch of mathematical science. A new, vast, and powerful language is developed for the future use of analysis, in which to wield its truths so that these may become of more speedy and accurate practical application for the purposes of mankind than the means hitherto in our possession have rendered possible. Thus not only the mental and the material but the theoretical and the practical in the mathematical world are brought into more intimate and effective connection with each other. We are not aware of its being on record that anything partaking in the nature of what is so well designated the Analytical Engine has been hitherto proposed, or even thought of, as a practical possibility, any more than the idea of a thinking or of a reasoning machine.

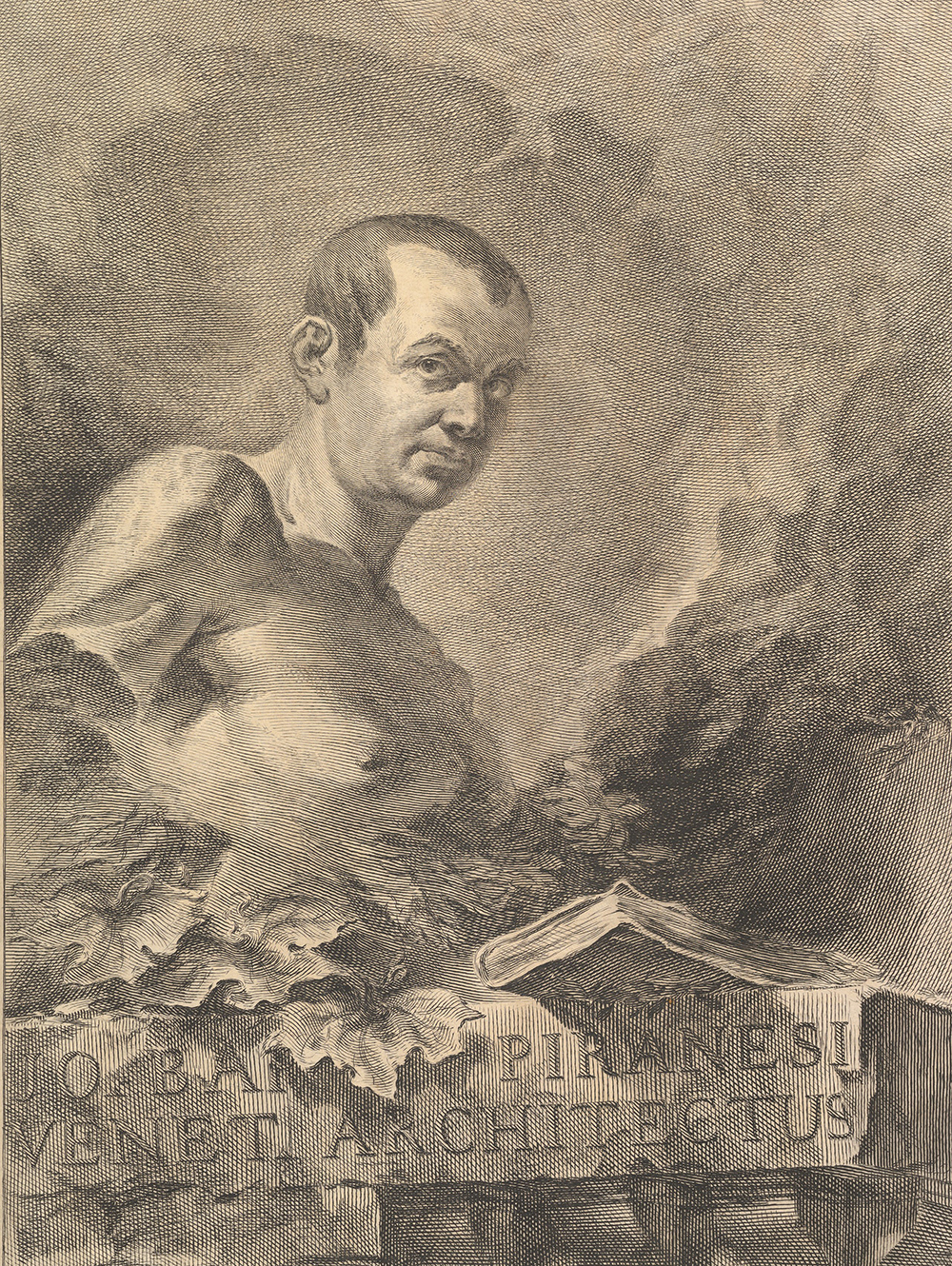

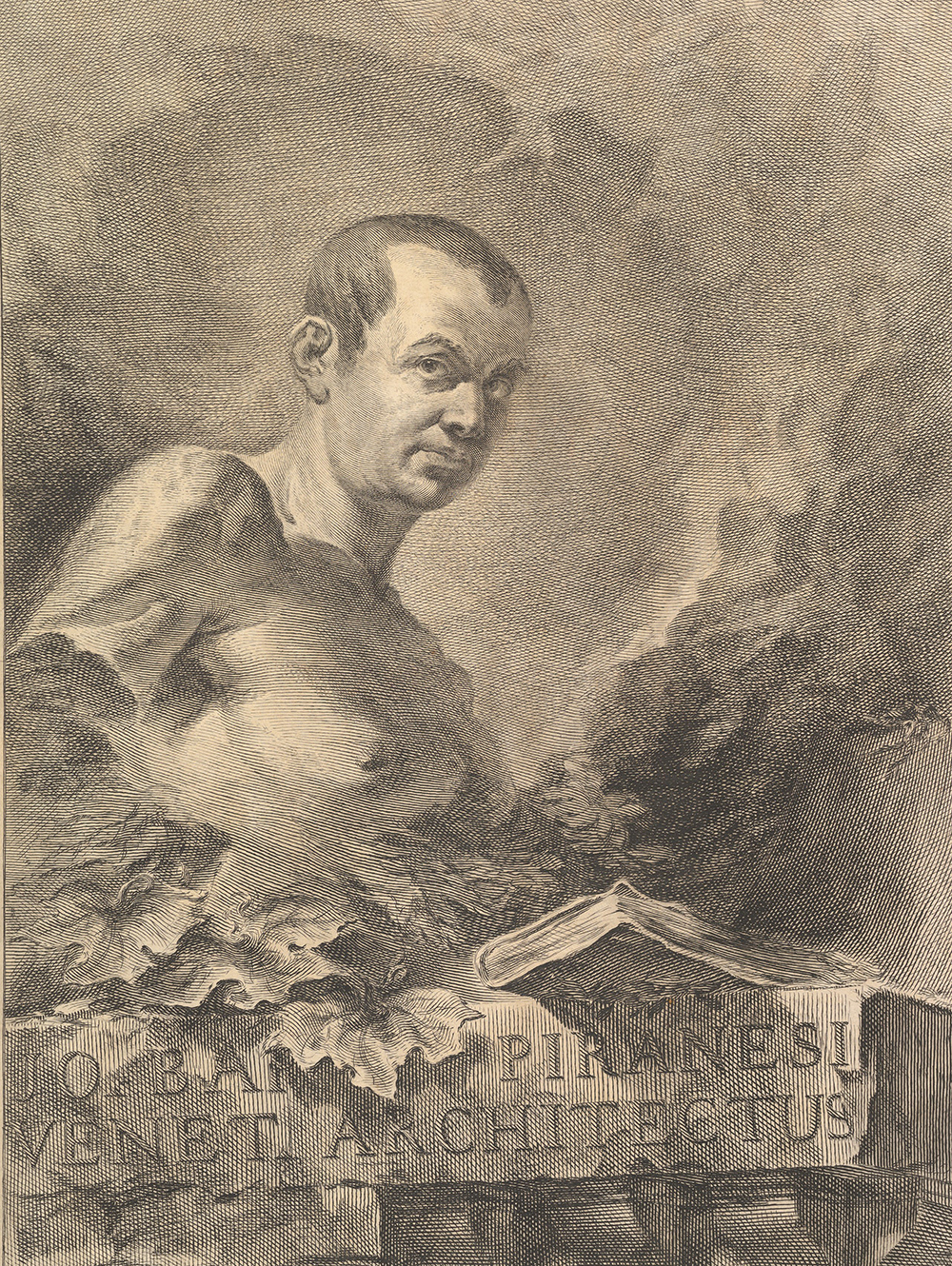

Portrait of Giovanni Battista Piranesi in Imitation of an Antique Bust, by Francesco Polanzani, 1750. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1937.

Those who incline to very strictly utilitarian views may perhaps feel that the peculiar powers of the Analytical Engine bear upon questions of abstract and speculative science, rather than upon those involving everyday and ordinary human interests. These persons being likely to possess but little sympathy, or possibly acquaintance, with any branches of science which they do not find to be useful (according to their definition of that word) may conceive that the undertaking of that engine would be a barren and unproductive laying out of yet more money and labor, in fact, a work of supererogation. Even in the utilitarian aspect, however, we do not doubt that very valuable practical results would be developed by the extended faculties of the Analytical Engine, some of which results we think we could now hint at, had we the space, and others which it may not yet be possible to foresee but which would be brought forth by the daily increasing requirements of science and by a more intimate practical acquaintance with the powers of the engine, were it in actual existence.

It is desirable to guard against the possibility of exaggerated ideas that might arise as to the powers of the Analytical Engine. In considering any new subject, there is frequently a tendency, first, to overrate what we find to be already interesting or remarkable, and secondly, by a sort of natural reaction, to undervalue the true state of the case when we do discover that our notions have surpassed those that were really tenable. The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform. It can follow analysis, but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths. Its province is to assist us in making available what we are already acquainted with. This it is calculated to effect primarily and chiefly, of course, through its executive faculties, but it is likely to exert an indirect and reciprocal influence on science itself in another manner. For in so distributing and combining the truths and the formula of analysis that they may become most easily and rapidly amenable to the mechanical combinations of the engine, the relations and the nature of many subjects in that science are necessarily thrown into new lights and more profoundly investigated. There are in all extensions of human power, or additions to human knowledge, various collateral influences beside the main and primary object attained.

From notes on Luigi Menabrea’s “Sketch of the Analytical Engine Invented by Charles Babbage.” In the mid-1830s, the mathematician Charles Babbage began designing a device capable of calculating any arithmetical function via a punch-card memory system inspired by the Jacquard loom. Though never completed, the Analytical Engine is considered the forerunner of the modern digital computer. In 1842 his colleague Menabrea published a description of it, and the following year Ada Lovelace, Lord Byron’s daughter and an associate of Babbage, translated the article into English, appending to it these annotations.

Back to Issue