Civilization, a much-abused word, stands for a high matter quite apart from telephones and electric lights.

—Edith Hamilton, 1930Living in a World Without Stars

This great reset offers little hope for the future of humanity.

By Curtis White

The Glow of Night—New York, by Alfred Stieglitz, 1897. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Charles Amos Cummings Fund.

I would set you free if I knew how. But it isn’t free out here. All the animals, the plants, the minerals, even other kinds of men, are being broken and reassembled every day, to preserve an elite few, who are the loudest to theorize on freedom but the least free of all.

—Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow

There is no alternative.

—Margaret Thatcher

i. who is klaus schwab, and why are people saying such terrible things about him?

Klaus Schwab is the founder and current chairman of the World Economic Forum and author, with economist Thierry Malleret, of 2020’s enormously controversial book Covid-19: The Great Reset. The World Economic Forum sponsors an annual conference in Switzerland, popularly known as Davos, an invitation-only event attended by industrial and governmental leaders from around the world. In the words of political scientist Samuel P. Huntington, the attendees of this forum are “Davos Men,” a wealthy global elite who “have little need for national loyalty, view national boundaries as obstacles that thankfully are vanishing, and see national governments as residues from the past whose only useful function is to facilitate the elite’s global operations.”

Now, Huntington was a Harvard Man and no right-wing conspiracy theorist, but this description is not far removed from the conclusions of a popular conspiracy fantasy that asserts—among many, many things—that the world is being taken over by global elites toiling against our interests under the banner of Schwab’s Great Reset. The claims get woollier from there: the Great Reset has also let loose Covid-19 in order to create conditions that would allow them to take control of world politics and economics, replace national currencies with cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, instate a communist dictatorship (aka the New World Order), and mandate a Covid vaccine containing a GPS tracker designed to provide universal police surveillance. In some versions of this theory, Donald Trump is the only leader keeping all this from happening.

I say this is a conspiracy fantasy because there is nothing theoretical or even hypothetical about it. It is not waiting for the right arrangement of material reality to confirm its conjectures. But then again, much of what we normally take for reality is largely a screen of clichés—ideological fantasies—that have no basis in fact but that we live through more or less willingly anyway. Evangelical salvation, American exceptionalism, personal wealth as a measure of virtue, patriotism, nationalism—all are dependent upon fantasies. These quotidian delusions provide a context in which right-wing conspiracy fantasies can seem plausible to some. For instance, if we can believe that the “founding fathers” convened with pure intent to provide “American freedom,” why can’t we imagine that people of impure intent conspire to take that freedom away? Even though none of this makes any sense at all, we are forbidden to say what’s true: there is not now, nor has there ever been, pure or impure, something a sober person might choose to call “American freedom.” To paraphrase Greg Palast, American freedom is the best freedom money can buy and always has been.

Schwab is not the first business theorist to describe our cybereconomy and its likely future. In 1990 inventor Ray Kurzweil published The Age of Intelligent Machines, and in 2001 there was former Lycos CEO Bob Davis’ book Speed Is Life. “We live in a world,” wrote Davis, “where a company is measured by its ability to accelerate everything from manufacturing to marketing, from hiring to distributing.” More recently, Richard Florida published The Great Reset in 2010 (a debt that Schwab does not acknowledge in his book), and in 2013 libertarian economist Tyler Cowen published Average Is Over: Powering America Beyond the Age of the Great Stagnation. Cowen’s book provides an account of the worker of the future, the “freestyler,” the human working in tandem with Kurzweil’s “intelligent machine.” Cowen writes, “If you and your skills are a complement to the computer, your wage and labor-market prospects are likely to be cheery. If your skills do not complement the computer, you may want to address that mismatch.”

The idea that the global cognoscenti are convinced that technology is the future of all global and regional economies comes as no surprise. What is perhaps surprising is an assumption that underlies their conviction: speed. Velocity. The idea that the future is coming at full speed has been common parlance among market savants for some time. They have argued that whether we like it or not, the cybereconomy of the future is “inevitable.” How do they know it is inevitable? Because it is happening fast. Worse yet, not only is it coming fast, but like the cosmos itself, it is accelerating. It is a force out of anyone’s control.

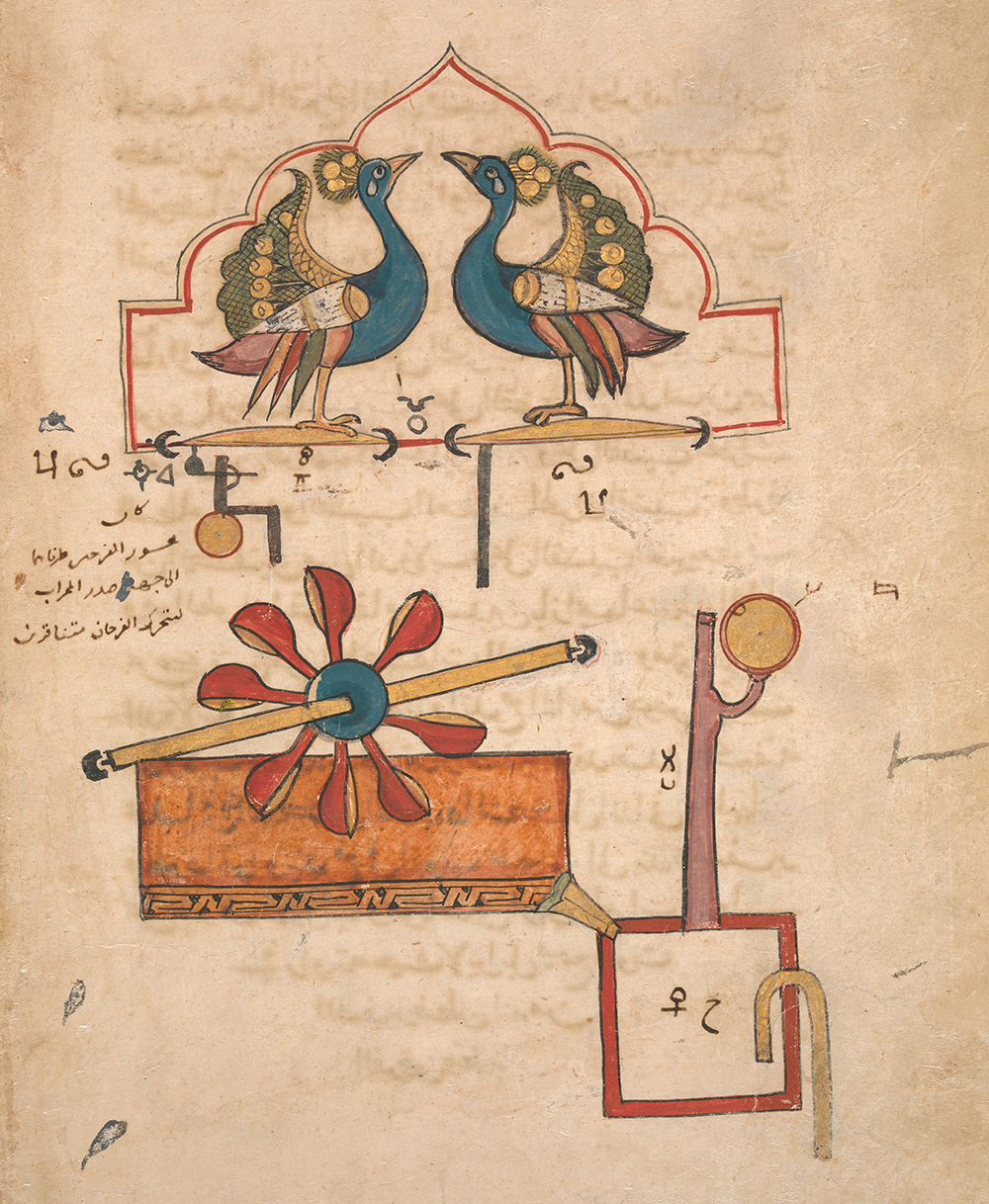

Water Clock of the Peacocks, miniature from a 1315 edition of al-Jazari’s Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1955.

On just two pages of Schwab’s The Great Reset, he uses words like fast, speed, accelerate, catalyze, turbocharge, change, and quick seventeen times. The use of these words is more than descriptive. Their repetition also has a subliminal function: anxiety. Something is coming! We’re told the following story by all of these technogurus: the age of the intelligent machine is near; it is inevitable; if you don’t prepare yourself for it, you will be left behind, you and your BA in European history. So if you’re lucky enough to go to college, be sure to study something in the STEM disciplines (science, technology, engineering, and math). If you don’t, you may find yourself un- or underemployed. So get on it!

Schwab’s and Cowen’s bottom line is that whether or not you study computer science at university, you will end up working with intelligent machines. There’s no escaping that. It’s only a matter of whether the work will be with computers in a shiny Google programming warehouse in California or with robots in a shiny Amazon fulfillment warehouse in Alabama. That’s the shape that the “prisoner’s dilemma” takes in the global economy of the present: shiny outside, unhappy inside, and millions of workers, isolated from one another by the very machines that are supposed to be their tools and unable to make common cause.

This is the situation, for real. Whatever the conspiracy-minded might like to add to it, this is bad enough.

ii. how is the great reset different from earlier theories about technocapitalism?

There is no new global order, just a chaotic transition to uncertainty.

—Jean-Pierre Lehmann

Schwab differs from Tyler Cowen and his ilk in his insistence that global capital will soon have no choice except to reform itself if it wishes to avoid “doom.” Schwab proposes that a global commitment to “environmental, social, and governance” crises is necessary if capitalism is to avoid systemic failure. He claims we will soon see “a new social conscience among large segments of the general population that life can be different.” Schwab concludes that the neoliberal era is finished, its grand assumption that all problems can be fixed by markets has come to an end. In particular, Covid-19 has shown that “just in time” global supply chains are too fragile to work dependably and that the neoliberal model must be replaced by structures that respect the importance of regions, states, and cities. “The model of globalization developed at the end of the last century,” he writes, “conceived and constructed by global manufacturing companies that were on the prowl for cheap labor, products, and components, has found its limits.” As a consequence, much more manufacturing will have to be done locally as a “hedge against disruption.”

Schwab also contends that business will be “subject to much greater government interference than in the past” in the form of “conditional bailouts, public procurement, and labor-market regulations.” As with the New Deal in the 1930s, Schwab proposes that corporations working for “stakeholders” rather than “shareholders” will save capitalism from itself and make possible another great compromise between business, government, and people. “The pandemic struck at a time when many different issues,” he writes, “ranging from climate-change activism and rising inequalities to gender diversity and #MeToo scandals, had already begun to raise awareness and heighten the criticality of stakeholder capitalism and environmental, social, and governance considerations in today’s interdependent world.” The claim that global capital is going to discover its inner FDR just in time to avoid calamity is based upon the assumption that there is sensitivity and unsuspected virtue within Davos Men, who say, with Shakespeare’s Shylock, “If you prick us, do we not bleed?” They, too, are people of feeling. Of course, this is just more mealymouthed special pleading by the ruling elite and is not so much a project for reform as it is another fantasy—the Davos Conspiracy Fantasy.

According to Schwab, the global elite is indeed conspiring at Davos, but it is conspiring in the name of justice, equality, and environmental health. In short, he argues that people like himself and the wealthy organizations that flock to his Davos confab each year should be trusted to right not only their own ships but all ships, in the name of a social conscience they have always possessed even if they haven’t always succeeded in showing it. Most surprisingly, given that we’re talking about Davos, Schwab suggests that “the ostentatious display of wealth will no longer be acceptable.” So no surprise if more Honda Civics and fewer Mercedes pull up to the curb at Davos.

Slack-jawed incredulity is required here, but it is probably strongest not among capitalism’s critics, people like me, but among the elite. The business elite enjoy Davos not for the preaching they hear from Schwab or from celebrities like Bono, Elton John, and Sharon Stone, but for the unique opportunity it provides for networking and deal making. The idea that they should give authority back to governments, reform labor relations, and put the needs of the environment before the need for profit will happen…in a pig’s eye.

After all, why should they change in the ways that Schwab says stakeholder capitalism requires? And why should anyone think capitalism needs to be saved from itself? This is not the Great Depression. There was no Black Tuesday and no execs dropped from the fifteenth floor, worthless stock certificates fluttering behind.

On the contrary, the Dow Jones Industrial Average increased during the pandemic, and the wealthiest among us saw their riches greatly increase. According to a study by 24/7 Wall St., the net worth of America’s 614 billionaires grew by a collective $931 billion during the first seven months of the pandemic. Big Tech execs have especially profited. For example, Twitter founder Jack Dorsey’s personal wealth grew by $7.8 billion (a 298 percent increase). Obviously, things are good for the billionaire class.

So the question becomes, since the pandemic has been profitable for the wealthy, why would they want to change anything? They have hated the New Deal for eighty years, and they have been buying up politicians to chip away at it, beginning with Ronald Reagan’s attacks on big government and the welfare state. What makes anyone think that capitalism is going to do an about-face after the past forty years of clawing back New Deal concessions? Why would they do that willingly, especially now? That being the case, well might we wonder just how much climate change and social unrest they will tolerate before they change their ways. My suspicion is that they’ll tolerate a lot, especially if stock markets continue to tell them that everything’s jake. They have no motive for following Schwab and every profit motive for not following him.

Schwab writes as if he doesn’t know his own people. While he spins ever-finer webs for a virtuous technofuture, his elite audience is thinking something far more primitive. They don’t care about Schwab’s sermons, and they don’t care about Davos except that they’re with the right people, the parties are nice, and maybe they’ll get to hang out with Matt Damon. What the Davos elite knows in its gut is Old Testament: the cost of labor is a threat to profit. So forget about helping workers, and don’t worry so much about social protest, people are replaceable—send in the clones!

Lynn Meadows, by Martin Johnson Heade, 1863. Yale University Art Gallery, gift of Arnold H. Nichols, B.A. 1920.

Of course, stock markets are saying something quite different to the people who have had their lives turned upside down in the last year, those millions whose only hope for survival is “quantitative easing,” either via “helicopter money” from the Fed or by unending unemployment checks—perverse pastures of plenty. What they are being told is this: In order for this economy to thrive, we don’t actually need you. We don’t need your labor, because robots and a few college kids will do ever more of the work. To which the unneeded must reply, “Yeah, but what am I supposed to do?” The answer to that question is becoming increasingly obvious: die. Die of Covid, die of poverty, or die of despair, but as much as possible, do it where you won’t be seen.

Schwab is selling a familiar cliché: if the system has problems, the system can fix them. But that is not what is happening. Quite the opposite. If on the one hand Amazon has hired hundreds of thousands of new workers during the Covid crisis, it has also resisted demands for worker safety and union representation at its warehouses, and it has greatly increased its investments in automation. Amazon’s warehouses are the ground floor of Tyler Cowen’s vision of an economy run on the backs of “freestyling” workers/robots. Freestyling sounds like fun, but the reality on the factory floor is awful: from 2016 to 2019 injuries were 50 percent higher at warehouses with robots. Bloomberg News described life in an Amazon warehouse:

Most of the labor in Amazon’s largest fulfillment centers is divided into simple, repetitive tasks: receiving goods arriving in trucks, placing items into mesh shelving, or retrieving and speeding them along a conveyor belt in yellow plastic bins to be boxed and shipped. Most jobs are marketed to high school graduates—no résumé required, start as soon as next week—who spend ten-hour shifts standing at a single station, cogs in a giant machine built for speed and efficiency.

Fritz Lang’s 1927 movie Metropolis, with its nightmare vision of mechanized humanity, has come into full flower—a lustrous neodymium corpse flower.

And what is the market answer to the environmental threats that Schwab claims to be concerned by? What will Davos Man do, for example, about water insecurity caused by drought and desertification? The answer to a possible water shortage is, naturally, to financialize it, to create market hedges against shortages by offering “water futures.” As Kim Chipman noted in December 2020 in Bloomberg Green:

Water joined gold, oil, and other commodities traded on Wall Street, highlighting worries that the life-sustaining natural resource may become scarce across more of the world. Farmers, hedge funds, and municipalities alike are now able to hedge against—or bet on—future water availability in California, the biggest U.S. agriculture market and world’s fifth-largest economy.

Thus while Schwab and the World Economic Forum impose a vast smiley face on our world, a greenwashing event like no other, they also show that they are, as Aeschylus wrote, “the slave of their own destruction.”

iii. is there an alternative to technocapitalism?

The new task of the nation-states is to manage what is allotted to them, to protect the interests of the market’s mega-enterprises, and above all to control and police the redundant.

—John Berger

We tend to think that the problem with the rich is simple: they are greedy. But it is more psychologically revealing to think of our plutocrats as residents in what Buddhism calls the god realm. On the Tibetan Wheel of Life, the topmost realm is occupied by the winners, the wealthy, and the privileged, for whom every benefit and pleasure is immediate and all suffering and ugliness is elsewhere. But the god realm is not only about greed—it is also about a certain psychology: anybody outside of the god realm doesn’t exist for the gods, mostly because they can’t be seen. It’s not only that our contemporary gods are cruel; it’s that others don’t exist for them except as data points—assessments of the public’s trust in brands, surveys of consumer optimism, wage growth, unemployment rates, savings rate, etc. The gods never see us, never mix with us, don’t know us except as flunkies and wage slaves, the redundant. We’re good for a laugh with our kooky conspiracy ideas, our community college degrees, our drug and alcohol melodramas, and our tawdry neighborhoods. Otherwise our world is terra incognita, a place of riot and malcontent, a place on the map where “there be monsters.”

Davos, on the other hand, is comforting. It is an annual public dramatization of the good life in the god realm. It’s a members-only event, badges are color-coded so there will be no confusion about who belongs and who doesn’t. CEOs, prime ministers, and some media elite get white badges; most journalists and support staff get orange and purple badges. It’s not as bad as swastikas and Stars of David, but you get the point.

For modern residents of the god realm, Schwab’s pleas do not summon their better angels. His moralizing appeals are an annoyance: the gods are being asked to recognize and give to people whose existence is little more than a rumor for them. The wealthy will not invite higher taxes on themselves to be used to fund enhanced social welfare and environmental conservation. It is more likely that they will sigh in frustration and say, “Hey, it was hard work snagging all that dough. I didn’t earn it in order to give it away for no good reason.”

Technology is so much fun, but we can drown in our technology. The fog of information can drive out knowledge.

—Daniel Boorstin, 1978A moment’s pause as the gods consider other lines of reasoning, then, “Okay, let’s be honest. There are too many people. Everybody says so. And most of them are losers, sleeping on sidewalks. I am a compassionate person, but my money won’t fix them. And frankly, these are people we don’t need anyway.” More honestly put, “Let the world die so long as I survive.”

This is not hyperbole or a joke in bad taste. It is a forced confession. As the pandemic revealed, the safety of workers in meatpacking plants, in the strawberry fields of California’s factory farms, and in hospital wards was secondary to the maintenance of corporate power and profit. In the words of William Rivers Pitt: “Capitalism demanded the nation not shut down and the workers keep working, even in the teeth of a lethal pandemic.” For Pitt, because minorities and immigrants do most of this work, capitalism’s indifference to their well-being is a form of genocide.

Reading The Great Reset is like walking on a boardwalk where the planks are unconnected and lie directly on the water. What waits below are the depths of the Real—death, poverty, and powerlessness. Death is the Real against which all conspiracy fantasies must be measured. The question I have is: Which conspiracy fantasy is the more deadly? The conspiracy fantasy that insists international elites are plotting to enslave us? Or the Davos Conspiracy Fantasy that insists stakeholder capitalism will bring greater equality and restore the earth? Davos and QAnon: weasels fighting in a hole.

Or is it simpler and sadder than that? Is it what William Butler Yeats expressed in his poem “Meditations in Time of Civil War”: “We had fed the heart on fantasies, / The heart’s grown brutal from the fare”?

If any real good is ever to come from Davos, it will come only when the gods throw away their badges and come down from their Alpine chalets. In Buddhist folklore, it was only when Prince Siddhartha left his father’s palace and saw for the first time poverty, sickness, and death that the way was opened for his awakening. Similarly, the capitalist class will not awaken until they come down from their twilight sanctuaries, their doomed Valhallas, and say, as the Dalai Lama says of himself, “I am no one special.”

And you know that is never going to happen. The gods are used to placing wagers, and they say, “The world may be burning, an angry mob may be at heaven’s gate, but I’ll take my chances up here.”

iv. does that mean margaret thatcher was right? there is no alternative?

[Workers] ought to inaugurate within the European beehive an age of a great swarming-out such as has never been seen before, and through this act of free emigration in the grand manner to protest against the machine, against capital…Once abroad, [they will] acquire a wild beautiful naturalness and be called heroism.

—Friedrich Nietzsche

The Great Reset is not a master plan for reform; it is just another enemy that capitalism has created in its own image and for its own convenience. It likes to be the home team playing the opposition within “friendly confines.” The elaborate moral edifice created by Klaus Schwab is a threat to no one. It is not a preamble to justice or freedom; it is just another “prisonhouse of language,” in Fredric Jameson’s telling phrase. However chaotic it may seem, however contemptible in its reasoning, however ridiculous in its slow dance with robots, the one thing technocapitalism takes comfort in is the certainty that there is nothing, especially no enemy, outside of it.

Inequality is surely a bad thing, destruction of the natural world a horror, but more devastating is to think that there is nothing outside of technocapitalism, no outside in which we can live differently. The only things outside of capital are the natural places it is destroying and will soon leave behind, what it glibly calls “sacrifice zones,” like the Bakken oil fields in Montana and North Dakota, or the 55,000 square miles of Alberta laid waste through tar-sand extraction, boreal songbirds up to their necks in the sludge. As the far-viewing novelist William T. Vollmann wrote in 1996:

More and more, the privileged people will work in their homes and shop from their homes and access the internet and play with their computers which will make the phosphor-dot worlds more and more real as the world outside continues to go to shit.

The outside has disappeared, just as the stars, the heavens themselves, are disappearing because of light pollution. Even on a butte in remote Zion National Park, the pollution from Las Vegas shadows the night skies—from 150 miles away. Which is a tragic fact, because it is a humbling privilege to look at the vastness of the heavens. But in the present, we can’t even see the galaxy we’re in, the Milky Way, never mind the billions of galaxies that load the rest of the cosmos and lead us to wonder if there are not other cosmos, multiverses, turning in their “old lonely immortal splendor,” as the poet Robinson Jeffers wrote, beyond our view but not beyond our imagining.

Now we see only what is boxed and immediately before us: property, or, much worse, virtual property, the internet of things. It’s like living in a closet and never knowing there is a living room not far away where friends wait for you. It’s the technological version of locked-in syndrome. This locked-in world for which there is no longer an outside is capitalism’s World According to Money. The empty sputtering of Klaus Schwab and the partygoers at Davos and the yammering of all the would-be Paul Reveres in conspiracy land produce only the hot air that inflates capitalism’s thrilling soap bubbles of status and the endless, lethal pursuit of money and things.

Fortunately, our situation has not always been so, nor must it so remain. Not long ago the curious communities that we knew as universities were part of an outside, a refuge, a counter-life, especially for students of the arts and humanities. In the 1950s and 1960s tuition was cheap, and so students felt freer to choose what they would study and what they would do with their lives. Now, though, universities are more like gateways to debtor’s prison. For oligarchs the ultimate benefit of student debt is that it is a very powerful tool for social regimentation. Should young people protest, the response is unequivocal and well understood: “This is the situation you were born into. It’s not discussible, so make the best of it.” This is naked coercion.

And it used to be that certain urban neighborhoods, like the Haight in San Francisco, the East Village in New York, and the Left Bank in Paris, provided cheap refuge for generations of students, artists, and miscellaneous dropouts, productively intermixed, well into the 1970s. And there were certain enlightened countercultural outposts, like Taos, New Mexico; Nevada City, California; and the Morning Star commune in Sonoma County. The powerful thing about these places was that you didn’t have to live in them in order to feel like you were part of their “scene.” Poetry from City Lights Bookstore, punk music from the Mudd Club, and art from the Lost Generation at Les Deux Magots, all were disseminated internationally on Radio Zeitgeist.

Assisi Forest Trail #2, by Susannah Hays, 2018. © Susannah Hays, courtesy the artist.

Does the living memory of such places provide an alternative to what Antonio Negri calls life in the “social factory”? Yes, because when such places return, they will be bigger in scale, mostly because we’re building on what was done in the past, although we may not be entirely aware of the fact. For instance, Covid-19 not only exposed how unequal we are, it also showed us how generous we are.

To take but one example, the phenomenal growth in the last disease-ridden year of mutual aid organizations shows that there is a willingness to leave the society of money behind and create a society of friends living in what is, at least in part, a gift economy, as opposed to an economy run through the grift. If the Davos plan is to let more money return to the people who made it, why not let it help to create places where people can live outside of technocapitalism? Or does Davos have the same fear that drove the Soviet Union to create the Iron Curtain: if we allow some to live in places outside of our social factory, they’ll all want to live there.

And of course art will survive, music will still be with us, showing that our values do not have to be the machine’s values. In spite of every unholy thing the world is, art offers self-valorization: this is the good, this the beautiful, this the world of spirit, all blessedly outside of capitalism’s tear-soaked social contract. The work of artists has always been an invitation to the rest of us to join them in a great swarming-out from Nietzsche’s beehive. While the geniuses at Davos try to get complexity right, art wants what is true, on the other side of money, where the stars are.