To gaze upon a drop of water is to behold the nature of all the waters of the universe.

—Huangbo Xiyun, 850

Newport Rocks, by John Frederick Kensett, 1872. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Thomas Kensett, 1874.

Few places would better qualify for hell on earth. In Basra, gas flares from oil wells shoot upward. They turn the sky orange at night and bake what is already one of the hottest places on earth by day. The ground is cooked to toast. The wreckage of past invasions and wars litters a landscape otherwise unremittingly barren and flat. Most of the palm trees that covered the surface have either wilted or been severed by shells. Slums spill out of Iraq’s decrepit second city, adding the black stench of sewage to the assault on the senses.

Out of the desolation flow the cleansing, balmy waters of the Ahwar, Iraq’s marshes. Barely an hour’s drive north on the highway from Basra, left at a derelict paper mill, and beyond an army checkpoint, herds of water buffalo slide into the cool shallows and bathe between the bulrushes. I went there in February, as spring was coming, and found Razaq Jabbar, a wizened boatman in a traditional black tunic crisply buttoned to the neck, waiting by his motorized mashoof, or gondola. He invited me and my traveling companions—Jassim al-Asadi, a director of Nature Iraq, which works to revive the wetlands, and my guide, Abbas al-Jabouri, and his teenage son—aboard, and steered his boat through a maze of reeds that bristled above marshlands stretching reassuringly beyond the horizon. As he sailed, he regaled us with the same songs he had sung a few months earlier to the Iraqi prime minister, Haider al-Abadi, in the same boat. He moaned for lovers lost forever in the harsh desert and delighted in new ones found among the wetlands. We clapped in accompaniment as he turned primordial fertility myths into song.

The return of the marshlands after a century of planned and unplanned desiccation is like Noah’s flood in reverse. Ever since the 1970s, Turkey and Syria had dammed the Euphrates River and its tributaries, curtailing the annual deluge that cooled and enriched Iraq’s flatlands with water and silt from Anatolia’s snowcapped mountains. Formerly fast-flowing waters slowed to a trickle, or on occasion stopped altogether. Fields lost their fecundity and turned to crust. The Middle East’s largest wetlands shrank and dried.

The military offenses of Saddam Hussein drained what remained. To flush out rebels, bandits, and army deserters hiding in the reeds after the Shia uprising in southern Iraq in 1991, his forces bombed the marshes, sowed mines in their waters, and buried the reeds beneath tarmac. They dug a bypass canal 350 miles long and, with a network of earthen dikes and sluice gates along the Euphrates, diverted its waters. Evaporation in the intense heat finished the job. With the bare land exposed, Iraq’s leader licensed companies to dig for oil and tapped one of the world’s richest oil fields, Majnoon, or “Madness.”

Without water the Madan, as the marsh Arabs of Ahwar are known, finally gave up their struggle for survival. For five thousand years they had withstood nature’s challenges. They had tamed the floodwaters of the great rivers and spawned the world’s earliest known civilizations and cities. Now they joined the ranks of the rural displaced converging on the slums ringing Iraq’s cities or fled for camps in Iran. The UN’s Environment Program called it “one of the earth’s major and most thoughtless environmental disasters.”

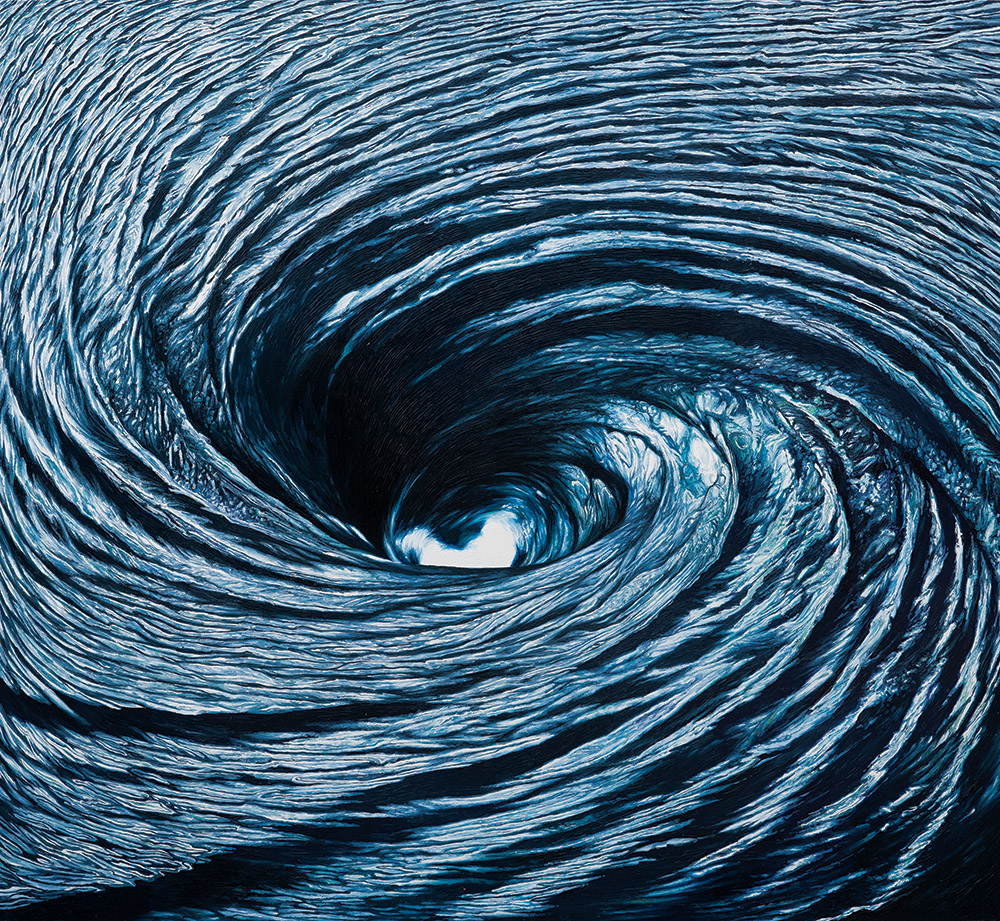

Our Relationship, by Chianxiang Shang, 2015. © Chianxiang Shang, courtesy the artist.

America’s invasion of Iraq in 2003 brought salvation, at least for the marshes. Paul Bremer, head of the coalition authority and Iraq’s proconsul, installed Abdul Karim al-Muhammadawi—a Madan guerrilla known as the Prince of the Marshes and head of the Shia armed group Iraqi Hezbollah—as one of Iraq’s twenty-five governing councillors. And the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers helped marsh Arabs bulldoze and breach the dikes and quench their parched land. As mud turned to marsh, foxes and falcons returned, searching for prey. So, too, did the flamingos and the marsh Arabs. Today, only the prowling lions are missing. Chibayish, the main town, has as many inhabitants as it did before Saddam Hussein drained the marshes. On the little artificial islands of reeds that poke from the water, families have rebuilt their mudhifs, or guesthouses. Dried reeds bound together rise twenty feet high like little town halls, and are fitted inside with cushions. Now, as five millennia ago, homes take three days to build and are assembled without nails, wood, or windows.

Razaq Jabbar moored beside one where women were frying their catch of the day. We lunched on qishta, or buffalo cream, and makhlama, ground meat cooked with scrambled eggs and vegetables. Reeds are the basis for life—for housing, fodder, and matting. In this resurgent local economy, women fish, milk buffalo, sow rice, and weave reed mats. Men more casually hunt birds and ferry groups of delighted Iraqi tourists between the reeds in their motorboats.

Old-timers complain the waters are tamer now. The marshland covers only a half of its 3,500-square-mile span of a generation ago. It once extended 70 miles west, to Abraham’s birthplace of Ur (now known as Nasiriyah), where a huge ziggurat rises out of the flats. But Razaq, the boatman, still remembers when floods were a regular occurrence. When the waters rose, his family would take to their boat and sometimes drift across borders into Iran. It might take a month before they moored again on dry land. Noah, the patriarch, might have remained afloat for longer, but the account of Al-Tufan, as the Flood is called in the Quran, sounded perfectly plausible. In winter, when the windows of heavens were opened and the fountains of the great deep broken up, as the Bible puts it, it was easy to imagine a biblical marsh sheikh building a vast boat to survive.

The Bible is frustratingly silent on Noah’s whereabouts, as it is on all of the pre-deluge patriarchs. Local lore as well as scriptural research cites that lost paradise in the marshlands between the two rivers, or Mesopotamia, as the Greeks called it. But what the Bible lacks in detail, local Akkadian, Sumerian, and Babylonian accounts of the flood myth provide. Ziusudra, Noah’s Sumerian counterpart, came from Shuruppak, near Tell Fa’rah, 135 miles south of Baghdad. The Mandaeans, an ancient Iraqi sect, still worship by venerating Noah and baptizing in the Euphrates. If myths have roots in reality, it seems likely the ark was assembled in the wetlands of southern Iraq.

While we were afloat on the marshes, childhood images of the ark came into view. I saw a huge wooden galleon painted by Flemish masters bursting at the seams with its cargo of animals. Elephant trunks and giraffe necks squeezed from windows. Camels and ostriches jostled for space a deck above. An entire aviary flew overhead. I made the mistake of sharing my musings with fellow passengers and was met with a chorus of rebuttals. What did seventeenth-century European artists know of the marshes? They modeled their arks on the merchant vessels that cruised the Pacific, not the craft of the marshes. How had the West drilled Eurocentric models into the human psyche, erasing the indigenous ship that the marshes might have produced? Could I not free my mind of its colonial implants and imagine the real ark?

I found an answer in a café opposite the Royal Academy in London, around the corner from my office. A bearded Iraqi artist bustled through the lunchtime rush carrying a reed basket the size of a beach ball. Rashad Salim placed it on the counter next to me and pronounced it to be a miniature replica of the real ark. Over the next hour he stripped me of the Western preconceptions I had derived from childhood puzzles. Noah would have dressed like a marshland boatman with a head scarf, not with the finery of a Renaissance Italian duke. He would have adapted local designs, not those of Europe’s shipyards three thousand years into the future. Dating back to a time when the Bronze Age was still in its infancy, his tools would have been rudimentary, fashioned from plants the marshlands still offer. Rope came from palm fronds woven as tight and strong as modern-day fibers. Thorns made good pins.

With the floodwaters rapidly rising, said Salim, Noah would not have had time to travel up the Euphrates and over the mountains to bring cedars from Lebanon. The hardwoods of the Flemish masters were a fantasy. Noah would have fashioned his boat from the trees that grew locally—palms, willows, and tamarisks. Pomegranate wands, prized for their flexibility, came from the orchards a day’s march north, beyond Hilla. Chiddem, natural pitch used for waterproofing, oozed to the surface in Hit, a short journey up the Euphrates.

They were techniques tried and tested over centuries. “Coated with chiddem, a coracle is as waterproof as fiberglass,” said Salim. “It can last for generations.” In the late 1970s, as a young mariner in his twenties, Salim had built a raft of reeds called the Tigris and sailed with the Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl on the last of his transoceanic adventures, from Iraq’s marshes across the Indian Ocean. In 2013, just before the jihadists of ISIS fanned across northern Iraq, he had boated down the Tigris River from Hasankeyf, Turkey. But reason, experience, and research suggested that a raft might have made an unlikely vessel to withstand the turbulent tides of a flood. And in search of the true ark, he delved deeper in search of ancient shipbuilding techniques. He scoured hundreds of flood myths for clues and interviewed old Madan craftsmen about the boats they built in an age when goods traveled between Basra and Babylon by river, not road.

For building blocks, concluded Salim after months of research, Noah would not have resorted to timber planks but to the locally made guffa, or coracle—a small round boat made of wicker. For millennia, until the juggernaut and the obstacle course of dikes and dams destroyed their business, the guffa had been the standard way of moving cargo. In old sepia photos, they bob in multiple sizes on the Tigris River, piled high with harvests and livestock bound for Baghdad’s markets. The larger ones—twelve feet in diameter—could carry a bull and its fodder. They surface in the Histories of Herodotus, the Greek chronicler of the fifth century bc, and, says Salim, on ancient Assyrian reliefs ferrying chariots over rivers some three thousand years ago. Roman commanders, he adds, even used Mesopotamian boatmen, or barcarii, to ship their imperial armies around that remote island of Britannia. Iraqi landscape artists painted them in the nineteenth century, and Freya Stark, a British explorer and travel writer, photographed them in Baghdad in the 1930s.

Under pressure of time and rising waters, reasoned Salim, Noah and his team of craftsmen would have strung together dozens of coracles with palm-frond rope and stuffed the cracks in between with bundles of reeds. Rather than make only a single vessel, they would have assembled a floating village. “I imagine the ark not as a unique boat of monumental size that had never been built before,” says Salim, “but as a gathering of many ordinary vessels. It would have been a community contained within a structure of unity that would protect them from catastrophe.” A huge mudhif, or perhaps an entire hamlet typical of those sprouting again in the marshes, would have covered the surface, sheltering the pairs of animals onboard. The more predatory might have had their own coracles, perhaps capped with cages. The entire contraption would have been two hundred feet wide, as large as the Moscow State Circus.

Salim’s reasoning was more empirical than scriptural. He applied the precept of Karl Marx that the environment, not God, determines outcomes. It was also fashionably anti-colonial. Salim comes from a distinguished line of revolutionary artists. His uncle, Jawad, worked with vast tableaux, one of which—the Monument of Liberation—is an iconic masterpiece that records the 1958 revolution against the British-backed monarchy and still dominates Tahrir Square in central Baghdad. Salim’s tableau was southern Iraq. “The environment and the heritage provide the material for my art,” he told me. “The ark is my monument.” Just as Jawad Salim’s work had helped free Iraqi minds from royal hierarchies, so his nephew was seeking to rid the world of its Eurocentric view of the ark and reclaim the flood myth for the land that inspired it—Iraq.

La Grenouillère (detail), by Claude Monet, 1869. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, H.O. Havemeyer Collection, bequest of Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, 1929.

That said, Salim’s coracle theory was not without scriptural foundations. The book of Genesis refers to an oblong ark, but the Hebrew word it used was teva, which appears only once elsewhere in the Bible—in Exodus to describe the crib or coracle in which Moses was placed in the bulrushes. Other ancient texts with striking similarities to the biblical flood story offer more clues. The Epic of Gilgamesh, which presents the Mesopotamian tale of the flood, describes how Enki, the god of water, tasks Utnapishtim, the last righteous man, to preserve creation from the flood by building a giant ship called the Preserver of Life and filling it with baby animals. Afloat on the earth, Utnapishtim, like Noah, sends out a dove and a raven and, when the latter fails to return, releases his cargo and offers a sacrifice to the divine. But among the commonalities, there are several vital differences. Tablet number eleven of Gilgamesh describes how Utnapishtim takes not only his immediate family on board the Preserver of Life but also various local craftsmen who helped build and maintain his floating village. And it lists the dimensions as being two hundred feet in length, width, and height and mentions a deck space of an acre. Gilgamesh’s ark, in other words, was round.

Salim’s current production is less ambitious in time and scope. He has found an old weaver and has commissioned enough coracles to assemble a half-size model of the Preserver of Life. He already has ten large coracles (at a cost of five thousand dollars each) and twenty-one smaller ones, and if all goes to plan, he will set sail at the end of the year, drifting from Babylon—the site of Nebuchadnezzar’s capital on the Euphrates—and head 250 miles downstream to the marshes. He will stage preliminary expeditions on Germany’s Rhine and England’s Thames to drum up awareness. He wants, he says, to reconnect global cultures to their natural environment. Through “a new social enterprise using art and design as a catalyst,” he hopes to show how humans could best survive catastrophe not by the construction of a single boat of monumental size but by joining many ordinary vessels into “a structure of unity.” His ark, he says, is a rant against individualism and an appeal for communal solidarity. It is a message he relays not just in the urban West, with its lack of community, but also back in his homeland, Iraq, soaked in the blood of sectarian and self-interested division.

In the meantime, Salim has hidden his thirty-one coracles, lest Iraq’s predatory government steal his idea. But he arranged for me to have a sneak viewing. Abbas al-Jabouri, his friend and driver, took me to his home near Babylon, where I found the coracles stacked to the ceiling in the hallway of the upper floor of his villa. Against the protests of al-Jabouri’s long-suffering wife, you had to clamber over them to reach the adjoining rooms. But al-Jabouri delighted in his new role as Salim’s shipbuilder and commissioner. No sooner had Iraq’s forces chased Islamic State fighters from Hit than al-Jabouri drove there to buy pitch for waterproofing the coracles. Tanks and troops filled the town, but al-Jabouri had a knack of negotiating the gruffest checkpoints. He would wind down the window and proclaim with funereal gravity, “Allah yirham amwatak” (May God have mercy on your dead). The guards, he explained, would be too honored to ask further questions.

Bubble, by Sarah Anne Johnson, 2011. Chromogenic print, embossed and screen printed. © Sarah Anne Johnson, courtesy Julie Saul Gallery, New York.

As in Gilgamesh, al-Jabouri was adamant that the ark builder would have needed faithful assistants like him. “Each coracle takes a month to make, but Noah wouldn’t have been working alone. He would have had the village working for him,” he said. Salim, he assured me, would follow Utnapishtim’s example, not Noah’s, and take him on board when the reimagined ark set sail. But al-Jabouri looks like a portly manager in jacket and tie, while Salim has the wild look of an ancient mariner. I was doubtful.

Few Iraqis, though, are as loyal as al-Jabouri. A prophet, after all, is never accepted in his hometown, and I found many Iraqis to be as mocking of Salim’s venture as the locals were of Noah’s. In Nasiriyah, beside the towering ziggurat of Ur, Abraham’s birthplace, I met Abdulameer al-Hamdani, a professor of antiquities and a well-traveled lecturer on the international circuit. He exuded the urbane formality of the roving academic. In his blue jacket and matching blue shirt, he was even more dapper than al-Jabouri. But the persona disguised a marsh Arab who spoke with the authority of experience. “Of course,” he told me after a brief exchange of introductions, “I grew up in the floods.” He had been born and raised in the marshes, and found the notion of survival for forty days and nights entirely conceivable. Before the mass construction of dams, as a child he had watched as his reed school rose off its island perch and floated downstream. He had kept moving ever since. He went to the University of Baghdad and then the State University of New York, where he wrote his doctorate on the wetlands. When we met, he was packing for a fresh post at Durham University in England to teach how to preserve endangered heritage in times of conflict.

Salim had suggested that al-Hamdani would shed light on the connection between the ark and his coracles, but within minutes he was debunking his theories. “I’ve lived on the marshes my entire youth. My father had a huge boat, but I’ve never seen a circular craft,” he told me. His readings of ancient cuneiform left him skeptical, too. “There’s no record anywhere of a round boat south of Babel,” says al-Hamdani. Ancient Sumerian and Assyrian reliefs and cylinder seals portray crescent-shaped rowing boats. And he found the notion of a circular ark moving upstream fanciful. Though they differ on the exact location of the ark’s final resting place, both the Bible and the Quran agree it was hundreds of miles to the north, in the mountains of Anatolia. Salim’s mission to populate the marshes with huge coracles seemed as alien as the tilapia that prey on the indigenous carp. He was also bothered by Salim’s sourcing of building materials. “I’ve never seen any boats made of palm trees. I’m not sure it would have lasted very long.”

The Flood has inspired many myths. Does the veracity of another one matter? Salim admits that his intention is less to prove what the ancient ark was like than to preserve what is meaningful and beautiful in the first civilization and protect it from the destruction of the contemporary one. Flying out of Iraq over Turkey, I looked over a landscape of man-made lakes flooding the highlands for the first time since Noah. A profusion of dams was again threatening habitation, this time one as old as civilization itself. Downstream, too, the dams have led to a fall in water levels in Iraq’s rivers by more than half in recent decades. Completion of Ilisu, one of the longest among the more than twenty-two dams Turkey is building along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers as part of its Southeastern Anatolia Project, has been mercifully delayed, but only until the summer of 2018. And Iran is the latest neighbor to dam its tributaries to the marshes. Over the past decade it has redirected the Karun River away from Iraq. Current water levels in the wetlands have diminished 40 percent from last year to less than a meter. The summer evaporation will send the levels even lower. Daily catches, complain the fisherwomen, have dropped by more than three-quarters. Yet Salim seems stoic. “Empires have come and gone, but until modern times we never lost our environment,” he says. If Salim’s ark can raise concern for the threatened marshlands, it, like Noah’s, might again save the first ecoculture from destruction.