The young man must store up, the old man must use.

—Seneca the Younger, 63Status Anxiety

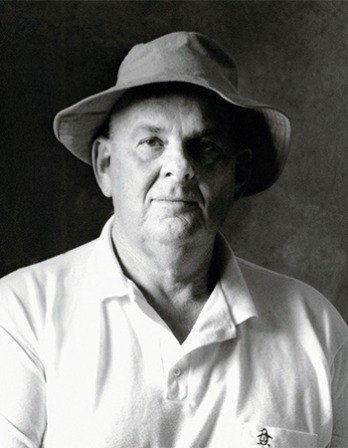

Albert Schweitzer on the terror of not fitting in.

I did not look for fights, but I loved to match bodily strength with others in friendly scuffles. One day on my way home from school, I wrestled with George Nitschelm—he now rests beneath the earth—who was taller and was considered stronger than I was, and I beat him.

As he was lying under me, he hissed, “Darn it, if I got soup with meat twice a week as you do, I would be as strong as you are!” Shaken by this outcome of the game, I staggered home. George Nitschelm had expressed with shocking clarity what I had already come to feel on other occasions. The village boys did not fully accept me as one of their own. To them I was one who was better off than they were—the parson’s son, the gentleman’s boy. I suffered because of this, for I did not want to be different from them or to be better off. The meat soup became loathsome to me. Whenever it was steaming on the table, I heard George Nitschelm’s voice.

From then on I anxiously tried not to distinguish myself from the others in any way. For the winter I had been given an overcoat made out of an old one of my father’s. But no village boy wore an overcoat. When the tailor tried it on me and said, “My goodness, Albert, you will soon be a monsieur!” I could hardly hold back my tears. On the day I was to wear it for the first time—it was on a Sunday morning for church—I refused. There ensued an ugly scene. My father slapped my face. To no avail. They had to take me along without the overcoat. After that each time I was supposed to wear the coat, the same thing happened. How many blows I received on account of that piece of clothing! But I stood my ground.

That same winter my mother took me with her to Strasbourg to visit an elderly relative. On that occasion she wanted to buy me a cap. In a fine store they had me try on a few. In the end, my mother and the saleswoman settled for a nice sailor’s cap, which I was to wear immediately. But they had reckoned without their host. The cap was unacceptable to me because none of the village boys wore a sailor’s cap. When they urged me to take it or another of the ones I had tried on, I made such a scene that everyone in the store rushed up to me. “Well, what kind of cap do you want, you silly boy?” the saleswoman snapped. “I don’t want any of your newfangled ones; I want one like the ones the village boys wear.” So they sent a salesgirl to get me a brown cap that could be pulled down over the ears, from the unsalable stock. Beaming with joy, I put it on while my poor mother had to endure a few “nice” remarks and scornful glances on account of her oaf.

It pained me that she felt ashamed before the city folk because of me. Still, she did not scold me. She must have had an inkling that something serious lay behind my behavior.

This hard struggle continued as long as I attended the village school and embittered not only my life but also that of my father. I wanted to wear mittens exclusively because the village boys did not wear any other kind of glove. On weekdays I wanted to walk only in clogs because they wore leather shoes only on Sundays. Every visitor who came rekindled the conflict, for I was supposed to present myself in clothes “befitting our social position.” While at home, I gave in to all demands; but whenever I was told to go for a walk with the visitor dressed as a “gentleman’s boy,” I became again the obstreperous fellow who infuriated his father—the courageous hero who endured being slapped and locked up in the cellar. Nevertheless, I suffered badly from rebelling against my parents. My sister Louise, who was a year older than I was, understood what I was going through and was touchingly sympathetic. The village boys did not know the cross I bore because of them. They coolly accepted all my efforts not to differ from them, but would, when the least quarrel occurred, wound me again with the terrible words gentleman’s boy.

At the beginning of my school years, I had to cope with one of the hardest lessons that life teaches us—a friend betrayed me. This is how it happened. When I first heard the word cripple, I did not know what it meant. It seemed to me to express a particularly strong dislike. One newly arrived teacher, Miss Goguel, had not yet earned my favor, so I bestowed the mysterious word upon her. When I was guarding the cows with my best friend, I confided to him in a secretive manner, “The teacher is a cripple, but don’t you tell anybody!” He promised.

Fresco of boxing boys, Akrotiri, Greece, sixteenth century BC. National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece.

On the way to school a short time afterward, we had a falling-out. Then he whispered to me on the stairs, “Okay, I’m going to tell the teacher that you called her a cripple.” I did not take the threat seriously, for I did not think such betrayal possible. But during the break he really did go up to the teacher’s desk and announced, “Miss, Albert said that you are a cripple.” Nothing came of it, for the teacher did not understand what the statement was supposed to mean. I, however, could not grasp the horror of it. This first experience of betrayal smashed to pieces everything that I had thought and expected of life. It took me weeks to get over the shock. I had lost my innocence about life. I bore within me the painful wound which life inflicts on us all and which it reopens again and again with new blows. Some of the blows I have received since then were harder than that first one, but none has hurt more.

Translated by Kurt and Alice R. Bergel. New York: Syracuse University Press, 1997. © 1997 by Syracuse University Press. Used with permission of Syracuse University Press.

Albert Schweitzer

From Memoirs of Childhood and Youth. While a member of the theological faculty at the University of Strasbourg, Schweitzer at the age of thirty published J. S. Bach: the Musician-Poet in 1905, the same year that he announced his desire to become a mission doctor. For the next six years he studied medicine at the university while continuing to teach there. In 1913 Schweitzer and his wife, a nurse, arrived in French Equatorial Africa, in present-day Gabon, and began to build a hospital. He worked in the area intermittently from 1927 to 1947.