Attacks on me will do no harm, and silent contempt is the best answer to them.

—James Monroe, 1808Overcorrection

Anton Chekhov reckons with the evil tongue.

Akhineyev, the teacher of penmanship, was marrying off his daughter Natalia to Loshadinikh, the instructor in geography and history.

The wedding festivities were in full swing. The hall resounded with singing, playing, and the scuffle of dancing feet. Hired servants in black frock coats and dirty white cravats were scurrying madly about the room. Tarantulov, the instructor in mathematics, the Frenchman Pasdequoi, and Msda, the junior inspector, were seated together on the sofa telling the guests, amid many interruptions and corrections, all the cases known to them of persons having been buried alive, and were moreover airing their views on spiritualism. None of the three believed in spiritualism, to be sure, but they were willing to admit there was much in this world that could not be explained by human intelligence.

In another room Dodonski, teacher of literature, was explaining the circumstances under which a sentry might fire upon civilians. The conversation was, as you see, a trifle gruesome, yet highly animated.

Through the windows, from without, looked in a crowd of envious people whose social position did not grant them the privilege of entrance.

At exactly midnight, the master of the house, Akhineyev, stepped into the kitchen to see whether all was ready for the wedding supper. From floor to ceiling the kitchen steamed with an aroma of geese, ducks, and countless other appetizing dishes. Upon two tables were beheld, in artistic disorder, the ingredients of a truly Lucullan banquet. And Marfa the cook, a buxom woman with a two-story stomach, was busy about the table.

“My dear woman, just let me have a look at that fish,” requested Akhineyev, chuckling and rubbing his palms together. “Mmm! What a delicious odor! Enough to make you eat the whole kitchen up! Let’s see that fish, do!”

Marfa went over to one of the chairs and carefully removed a greasy newspaper, underneath which there reposed upon a gigantic platter a huge whitefish, garnished with capers, olives, and vegetables. Akhineyev looked at the fish and almost melted with rapture. His countenance beamed; his eyes almost popped out of their sockets. He leaned forward and with his lips made a sound resembling the squeal of an ungreased axle. For a moment he stood motionless, then snapped his fingers and smacked his lips again.

“Aha! The music of a passionate kiss. Whom are you kissing there? Marfa?” came a voice from the adjoining room, and in the doorway there appeared the close-cropped head of Akhineyev’s colleague Vanykin.

“Who is the lucky fellow? Aha…fine! Mr. Akhineyev himself! Bravo, Grandpa! Excellent! A nice little tête-à-tête with a charming lady.”

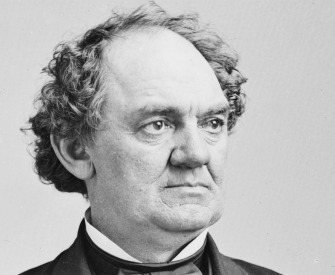

Man with the Moneybag and Flatterers, by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, c. 1592. © HIP / Art Resource, NY.

“I’m not kissing anybody,” retorted Akhineyev, embarrassed. “What an idea! You…I was merely smacking my lips…with delight…as I looked upon the fish here.”

Vanykin’s features wrinkled with laughter and he disappeared. Akhineyev turned red.

“The deuce!” he thought. “Now this fellow is going around everywhere gossiping about me. A thing like this can easily spread through the whole city. The jackass!”

Akhineyev returned to the hall shyly and glanced furtively in all directions for Vanykin. That worthy was standing by the piano telling something in his most cavalier-like manner to the inspector’s mother-in-law, who smiled in evident pleasure.

“It’s about me!” suspected Akhineyev. “About me, devil take the rascal! And she, she believes every word and laughs! Such a silly goose! Good God! No, I must not allow this. No, I must do something to discredit him in advance. I’ll speak to everybody about the incident and unmask him as a stupid gossipmonger!”

Akhineyev scratched himself and then, still in embarrassment, walked over to Pasdequoi.

“I was just in the kitchen to settle some details about the supper,” he said to the Frenchman. “I know that you’re very fond of fish, and I’ve got one down there about two yards long. He-he! Yes, and then—I almost forgot it—in the kitchen just now, such a funny joke! You see, I come into the kitchen and want to take a look at the dishes. I see the fish and from sheer delight…such a splendid specimen…I smacked my lips. And at this very moment, in pops that bad sheep Vanykin and says…ha-ha!…and says, ‘Aha! You’re kissing somebody here?’ Such a fool, imagining that I was kissing Marfa the cook! Why, that woman looks as if…Fie! To kiss a thing like her! There’s a fool for you! Such a dub!”

“Who’s that?” asked Tarantulov, coming in.

“Vanykin! You see, I come into the kitchen…”

The tale of Marfa and the fish was repeated.

“Think of it! Why, I’d just as soon kiss a mongrel as kiss Marfa.” And Akhineyev, turning around, noticed Msda.

“We were just speaking of Vanykin,” said Akhineyev to Msda. “Such a simpleton! Pops into the kitchen, sees me near Marfa the cook and at once makes up a whole story. ‘So, you’re kissing Marfa?’ says he to me. He was a little bit tipsy, upon my word! And I answered that I’d sooner kiss a turkey than kiss Marfa. And I reminded him, too, that I was a married man. Think of his silly idea! Ridiculous!”

“What’s ridiculous?” asked the rector, happening to pass by.

“That chap Vanykin. I’m in the kitchen, you understand, looking at the fish…”

And so forth. In the course of a half hour, nearly all the guests were fully informed of the story of the fish.

“Now let him tell as many people as he wishes,” thought Akhineyev, rubbing his palms. “Just let him! As soon as he begins, I can say to him, ‘Spare your breath, dear friend! We know all about it already!’ ”

And the thought so comforted Akhineyev that he drank four glasses more than were good for him. After the supper he led the newlywed couple to the bridal chamber, went to bed, and slept like a log. By the next morning he had forgotten the tale of the fish completely. But woe! Man proposes and God disposes. The evil tongue accomplished its wicked work, and Akhineyev’s cunning was all in vain! Exactly a week later, on a Wednesday, just after the third lesson had begun and Akhineyev was standing in the classroom correcting the exaggerated slope of the pupil Vissekin’s handwriting, the director stepped over to him and called him to one side.

“My dear Mr. Akhineyev,” said the director. “You will pardon me. It is really none of my business, but I must speak to you about it. It is my official duty. You must know that the rumor is running through the city that you have certain relations with…with your cook. Of course, it’s no affair of mine, as I have said, but live with her, kiss her to your heart’s content. But I beg of you, not so publicly! I beg of you! Do not forget your high calling!”

A cold shiver ran down Akhineyev’s spine, and he lost his self-composure. As if he had been stung by a gigantic swarm of bees or scalded with boiling water, he flew to his home. On the way it seemed to him that the whole city was staring at him as if he had been tarred and feathered. At home a new vexation was awaiting him.

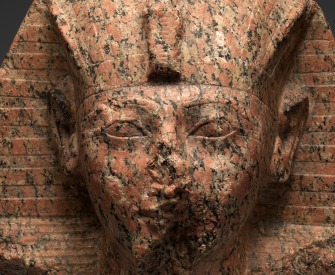

Saint Peter realizing he has thrice betrayed Jesus, miniature from the Leggendario Sforza-Savoia, by Cristoforo de Predis, 1476. © Album / Art Resource, NY.

“Why don’t you eat?” asked his wife at dinner time. “What are you dreaming about? Your love? Are you yearning for Marfa? You Muhammadan, you! I know everything! My eyes have been opened! You barbarian!”

And slap! He received a blow over the cheek. He arose from the table, and as if in a trance, with neither hat nor coat, he went to Vanykin. He found Vanykin at home.

“You slanderer!” cried Akhineyev, turning on him. “Why have you soiled my reputation before the whole world? How dare you have slandered me!”

“What do you mean slandered? Where did you ever get that notion?”

“Then who did invent the story that I had been kissing Marfa? I suppose it wasn’t you, eh? Not you, eh?”

Vanykin’s eyes began to blink, his whole lively countenance was convulsed with twitching. Raising his eyes to the icon in the corner, he cried out, “May God punish me! I swear by the salvation of my soul that I never repeated a word of the story! May I be cursed with eternal damnation! May I…”

There was no questioning Vanykin’s sincerity. It was clear that he had not spread the gossip.

“But who then? Who?” muttered Akhineyev, beating his fists against his breast and mentally going over the list of all his friends. “Who then?”

Anton Chekhov

“A Slander.” “I have a horror of weddings,” Chekhov wrote to his wife in 1901. “The congratulations and the champagne, standing around, glass in hand, with an endless grin on your face.” The son of a former serf, Chekhov began his literary career in Moscow during the 1880s, writing humorous magazine pieces to support his family while studying to become a doctor. By the time he died, in 1904, he had written some five hundred short stories. “Chekhov’s comic sketches,” wrote the Russian scholar Alexander Chudakov, “always take some fragment of life, with no beginning or end, and simply offer it for inspection.”