Dear Sir,

It is an observation of a wise man that “moderation is best in all things.” I cannot agree with him “in liquor.” There is a smoothness and oiliness in wine that makes it go down by a natural channel, which I am positive was made for that descending. Else, why does not wine choke us? Could Nature have made that sloping lane not to facilitate the downgoing? She does nothing in vain. You know that better than I. You know how often she has helped you at a dead lift, and how much better entitled she is to a fee than yourself sometimes, when you carry off the credit. Still there is something due to manners and customs, and I should apologize to you and Mrs. Asbury for being absolutely carried home upon a man’s shoulders through Silver Street, up Parson’s Lane, by the Chapels (which might have taught me better), and then to be deposited like a dead log at Gaffar Westwood’s, who it seems does not “insure” against intoxication. Not that the mode of conveyance is objectionable. On the contrary, it is more easy than a one-horse chaise. Ariel in The Tempest says, “On a bat’s back do I fly, / after sunset merrily.” Now, I take it that Ariel must sometimes have stayed out late of nights. Indeed, he pretends that “where the bee sucks, there lurks he,” as much as to say that his suction is as innocent as that little innocent (but damnably stinging when he is provoked) winged creature. But I take it that Ariel was fond of metheglin, of which the bees are notorious brewers. But then you will say, What a shocking sight to see a middle-aged gentleman-and-a-half riding upon a gentleman’s back up Parson’s Lane at midnight. Exactly the time for that sort of conveyance, when nobody can see him, nobody but heaven and his own conscience; now, heaven makes fools, and don’t expect much from her own creation; and as for conscience, she and I have long since come to a compromise. I have given up false modesty, and she allows me to abate a little of the true. I like to be liked, but I don’t care about being respected. I don’t respect myself. But, as I was saying, I thought he would have let me down just as we got to Lieutenant Barker’s coal shed (or emporium) but by a cunning jerk I eased myself and righted my posture. I protest, I thought myself in a palanquin, and never felt myself so grandly carried. It was a slave under me. There was I, all but my reason. And what is reason? And what is the loss of it? And how often in a day do we do without it, just as well? Reason is only counting, two and two makes four. And if on my passage home, I thought it made five, what matter? Two and two will just make four, as it always did, before I took the finishing glass that did my business. My sister has begged me to write an apology to Mrs. A and you for disgracing your party; now it does seem to me that I rather honored your party, for everyone that was not drunk (and one or two of the ladies, I am sure, were not) must have been set off greatly in the contrast to me. I was the scapegoat. The soberer they seemed. By the way, is magnesia good on these occasions? I am no licentiate, but know enough of simples to beg you to send me a draft after this model. But still you will say (or the men and maids at your house will say) that it is not a seemly sight for an old gentleman to go home pickaback. Well, maybe it is not. But I never studied grace. I take it to be a mere superficial accomplishment. I regard more the internal acquisitions. The great object after supper is to get home, and whether that is obtained in a horizontal posture or perpendicular (as foolish men and apes affect for dignity) I think is little to the purpose. The end is always greater than the means. Here I am, able to compose a sensible rational apology, and what signifies how I got here? I have just sense enough to remember I was very happy last night, and to thank our kind host and hostess, and that’s sense enough, I hope. N.B. What is good for a desperate headache? Why, patience, and a determination not to mind being miserable all day long. And that I have made my mind up to. So, here goes. It is better than not being alive at all, which I might have been, had your man toppled me down at Lieutenant Barker’s coal shed. My sister sends her sober compliments to Mrs. A. She is not much the worse.

Yours truly,

Charles Lamb

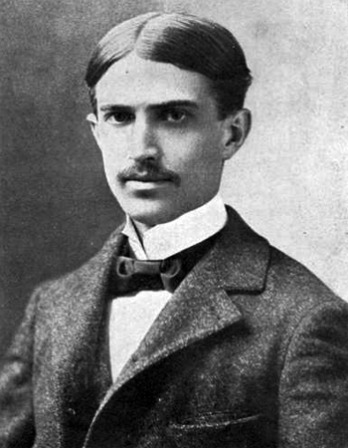

From a letter to James Vale Asbury. Lamb began writing personal and critical essays for London Magazine under a pseudonym in 1820, collecting the works into the books Elia in 1823 and The Last Essays of Elia in 1833. He wrote to his friend William Wordsworth in 1801, “Separate from the pleasure of your company, I don’t much care if I never see a mountain in my life.” Twenty-nine years later, he wrote to the same correspondent, “What have I gained by health? Intolerable dullness. What by early hours and moderate meals?—a total blank.” Lamb died in 1834.

Back to Issue