Let a man of the middle class approach a woman of the same class and address her in this manner:

First he should greet her in his usual way; this, however, should always be done, and all lovers must realize that after the salutation they should not immediately begin talking about love, for it is only with their concubines that men begin in that way. On the contrary, after the man has greeted the woman, he ought to let a little time elapse so that she may, if she wishes, speak first. If she does begin the conversation, you have good reason to rejoice, unless you are a fluent talker, because her remark will give you plenty to talk about. There are men who in the presence of ladies so lose their power of speech that they forget the things they have carefully thought out and arranged in their minds; they cannot say anything coherent, and it seems proper to reprove their foolishness, for it is not fitting that any man, unless he is bold and well-instructed, should enter into a conversation with ladies. But if the woman waits too long before beginning the conversation, you may begin it yourself, skillfully. First you should say things that have nothing to do with your subject—make her laugh at something, or else praise her home, or her family, or herself. Because women—particularly middle-class women from the country—commonly delight in being commended and readily believe every word that looks like praise. Then after these remarks that have nothing to do with your subject, you may go on in this fashion:

“When the Divine Being made you, there was nothing that He left undone. I know that there is no defect in your beauty, none in your good sense, none in you at all except, it seems to me, that you have enriched no one by your love. I marvel greatly that Love permits so beautiful and so sensible a woman to serve for long outside his camp. O, if you should take service with Love, blessed above all others will that man be whom you shall crown with your love! Now if I, by my merits, might be worthy of such an honor, no lover in the world could really be compared with me.”

The woman says, “You seem to be telling fibs, since although I do not have a beautiful figure you extol me as beautiful beyond all other women, and although I lack the ornament of wisdom, you praise my good sense. The very highest wisdom ought not to be required of a woman descended from the middle class.”

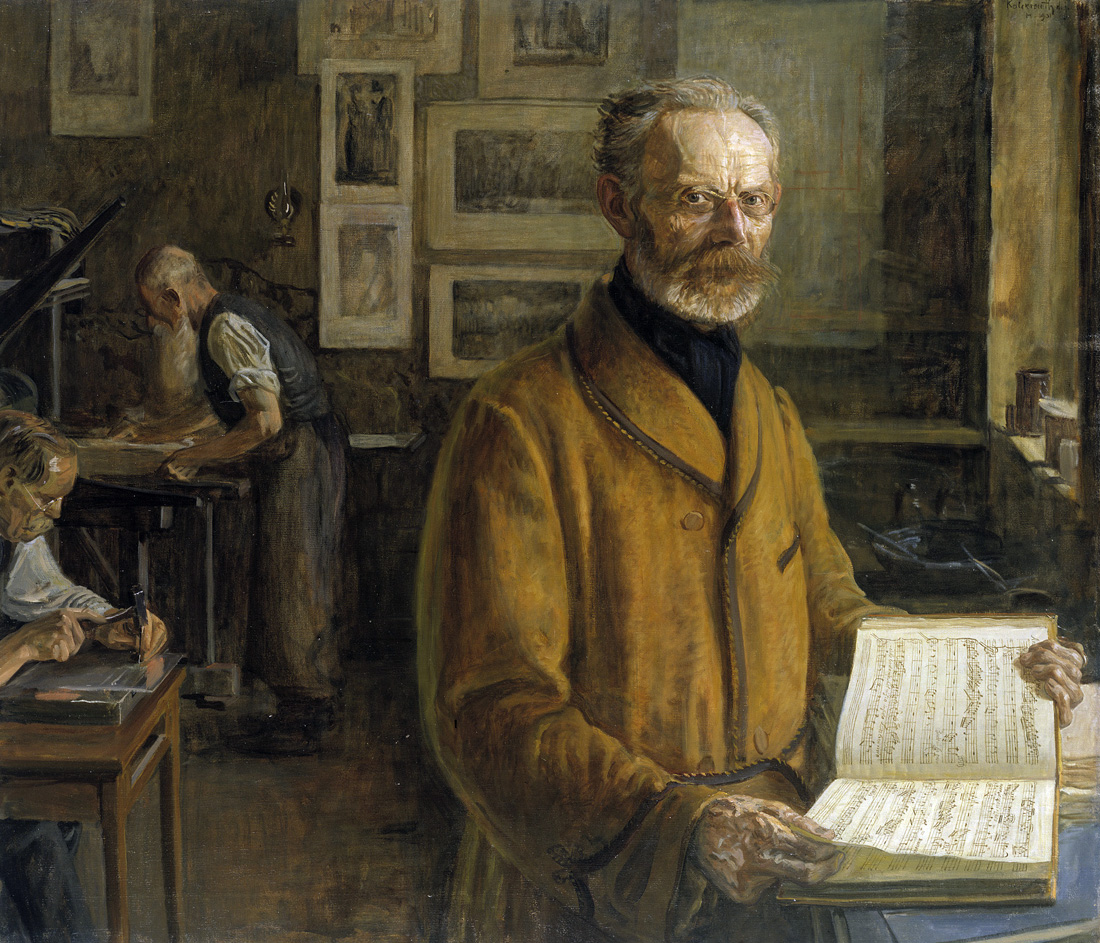

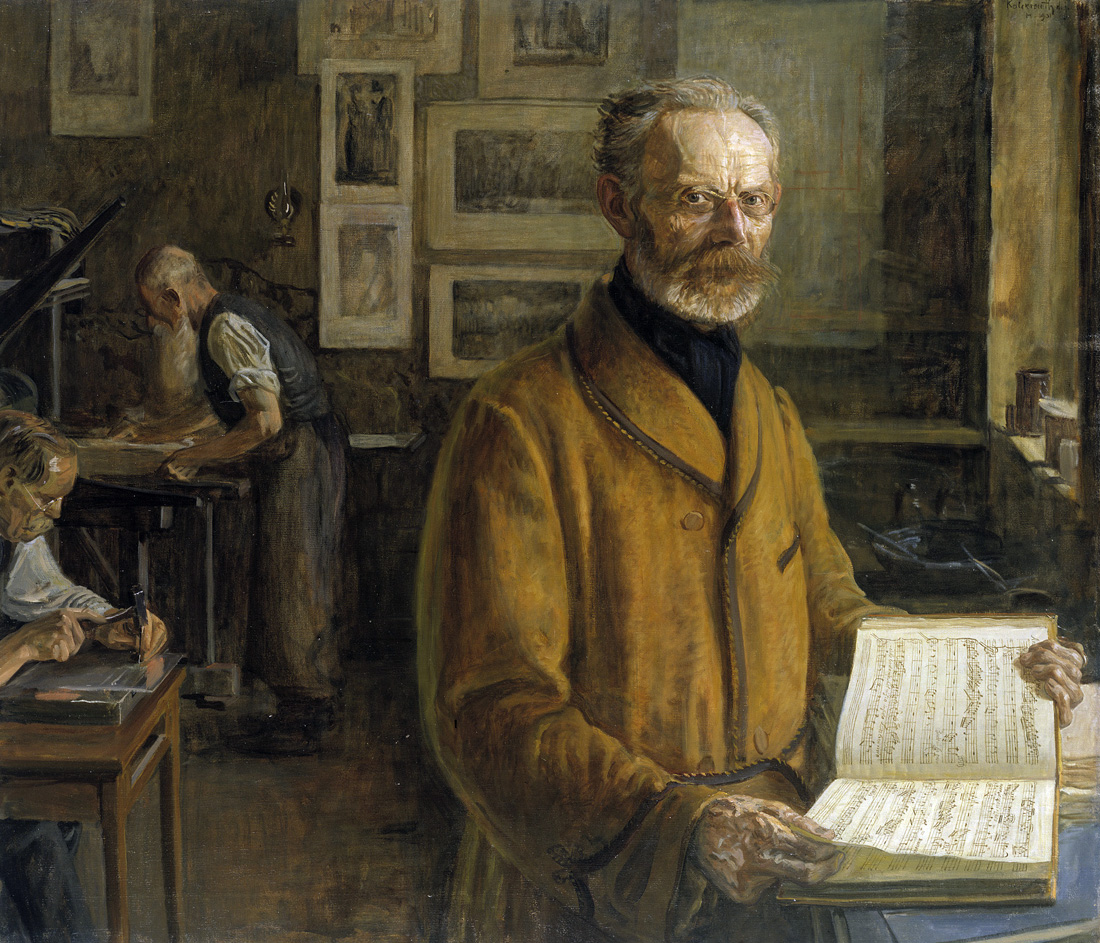

Portrait of Friedrich Chrysander, German music historian, by Leopold Graf von Kalckreuth, 1901. Kunsthalle, Hmaburg, Germany.

The man says, “It is a habit of wise people never to admit with their own mouths their good looks or their good character, and by so doing they clearly show their character, because prudent people guard their words so carefully that no one may have reason to apply to them that common proverb which runs, ‘All praise is filthy in one’s own mouth.’ You, like a wise woman, not wishing to fall foul of this saying, leave all praise of you to others, but there are so many who do praise you that it would never be right to say that any of them meant to tell fibs. Even those who do not love you for the sake of your family are, I know, diligent in singing your praises. And besides, if you think you are not beautiful, you should believe that I must really be in love, since to me your beauty excels that of all other women, and love makes even an ugly woman seem very beautiful to her lover. You said too that you come of a humble family. But this shows that you are much more deserving of praise and blessed with a greater nobility, since yours does not come from your descent or from your ancestors, but good character and good manners alone have given to you a more worthy kind of nobility.

The woman says, “If I am as noble as you are trying to make out, you, being a man of the middle class, should seek the love of some woman of the same class, while I look for a noble lover to match my noble status; for nobility and commonality ‘do not go well together or dwell in the same abode.’”

The man says, “Your answer would seem good enough if it were only in women that a lowly birth might be ennobled by excellence of character. But since an excellent character makes noble not only women but men also, you are perhaps wrong in refusing me your love, since my manners, too, may illumine me with the virtue of nobility. Your first concern should be whether I lack refined manners, and if you find my status higher than you would naturally expect, you ought not deprive me of the hope of your love. For one whose nobility is that of character, it is more proper to choose a lover whose nobility is of the same kind than one who is highborn but unmannerly. Indeed, if you should find a man who is distinguished by both kinds of nobility, it would be better to take as a lover the man whose only nobility is that of character. For the one gets his nobility from his ancient stock and from his noble father and derives it as a sort of inheritance from those from whom he gets his being, but the other gets his nobility only from himself, and what he takes is not derived from his family tree but springs only from the best qualities of his mind.”

The woman says, “You may deserve praise for your great excellence, but I am rather young, and I shudder at the thought of receiving solaces from old men.”

©1960 by Columbia Univeristy. Used with permission of Columbia University Press.

From The Art of Courtly Love. Little is known about Andreas other than that he was a French cleric—perhaps a chaplain at the court of Marie, countess of Champagne, daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine. A child of the twelfth-century renaissance, he lived during the period in which major works of Aristotle were rediscovered and the scholastic liberal arts were revitalized. The treatise drew upon both the vernacular verse of troubadors and the love lyrics of Ovid.

Back to Issue