No one gossips about other people’s secret virtues.

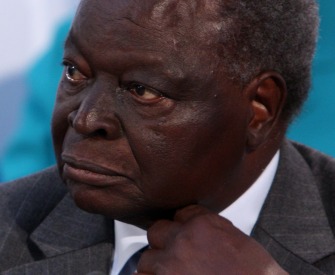

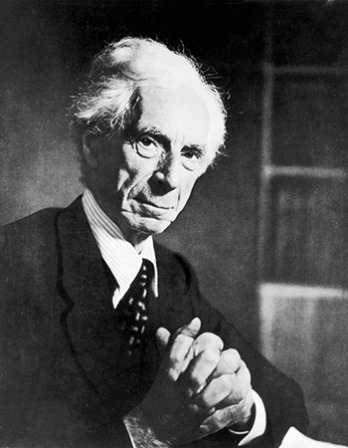

—Bertrand Russell, 1961Telling a True War Story

Tim O’Brien searches for what is real in war.

In any war story, but especially a true one, it’s difficult to separate what happened from what seemed to happen. What seems to happen becomes its own happening and has to be told that way. The angles of vision are skewed. When a booby trap explodes, you close your eyes and duck and float outside yourself. When a guy dies, you look away and then look back for a moment and then look away again. The pictures get jumbled; you tend to miss a lot. And then afterward, when you go to tell about it, there is always that surreal seemingness, which makes the story seem untrue, but which in fact represents the hard and exact truth as it seemed.

In many cases a true war story cannot be believed. If you believe it, be skeptical. It’s a question of credibility. Often the crazy stuff is true and the normal stuff isn’t, because the normal stuff is necessary to make you believe the truly incredible craziness.

In other cases you can’t even tell a true war story. Sometimes it’s just beyond telling.

I heard this one, for example, from Mitchell Sanders. It was near dusk and we were sitting at my foxhole along a wide muddy river north of Quang Ngai City. I remember how peaceful the twilight was. A deep pinkish-red spilled out on the river, which moved without sound, and in the morning we would cross the river and march west into the mountains. The occasion was right for a good story.

“God’s truth,” Mitchell Sanders said. “A six-man patrol goes up into the mountains on a basic listening-post operation. The idea’s to spend a week up there, just lie low, and listen for enemy movement. They’ve got a radio along, so if they hear anything suspicious—anything—they’re supposed to call in artillery or gunships, whatever it takes. Otherwise they keep strict field discipline. Absolute silence. They just listen.”

Sanders glanced at me to make sure I had the scenario. He was playing with his yo-yo, dancing it with short, tight strokes of the wrist.

His face was blank in the dusk.

“We’re talking regulation, by-the-book LP. These six guys, they don’t say boo for a solid week. They don’t got tongues. All ears.”

“Right,” I said.

“Understand me?”

“Invisible.”

Sanders nodded.

“Affirm,” he said. “Invisible. So what happens is, these guys get themselves deep in the bush, all camouflaged up, and they lie down and wait and that’s all they do, nothing else, they lie there for seven straight days and just listen. And man, I’ll tell you—it’s spooky. This is mountains. You don’t know spooky till you been there. Jungle, sort of, except it’s way up in the clouds and there’s always this fog—like rain, except it’s not raining—everything’s all wet and swirly and tangled up and you can’t see jack, you can’t find your own pecker to piss with. Like you don’t even have a body. Serious spooky. You just go with the vapors—the fog sort of takes you in…and the sounds, man. The sounds carry forever. You hear stuff nobody should ever hear.

Sanders was quiet for a second, just working the yo-yo, then he smiled at me.

“So after a couple days the guys start hearing this real soft, kind of wacked-out music. Weird echoes and stuff. Like a radio or something, but it’s not a radio, it’s this strange gook music that comes right out of the rocks. Faraway, sort of, but right up close, too. They try to ignore it. But it’s a listening post, right? So they listen. And every night they keep hearing that crazy-ass gook concert. All kinds of chimes and xylophones. I mean, this is wilderness—no way, it can’t be real—but there it is, like the mountains are tuned in to Radio fucking Hanoi. Naturally they get nervous. One guy sticks Juicy Fruit in his ears. Another guy almost flips. Thing is, though, they can’t report music. They can’t get on the horn and call back to base and say, ‘Hey, listen, we need some firepower, we got to blow away this weirdo gook rock band.’ They can’t do that. It wouldn’t go down. So they lie there in the fog and keep their mouths shut. And what makes it extra bad, see, is the poor dudes can’t horse around like normal. Can’t joke it away. Can’t even talk to each other except maybe in whispers, all hush-hush, and that just revs up the willies. All they do is listen.”

Again there was some silence as Mitchell Sanders looked out on the river. The dark was coming on hard now, and off to the west I could see the mountains rising in silhouette, all the mysteries and unknowns.

“This next part,” Sanders said quietly, “you won’t believe.”

“Probably not,” I said.

“You won’t. And you know why?” He gave me a long, tired smile. “Because it happened. Because every word is absolutely dead-on true.”

Sanders made a sound in his throat, like a sigh, as if to say he didn’t care if I believed him or not. But he did care. He wanted me to feel the truth, to believe by the raw force of feeling. He seemed sad, in a way.

“These six guys,” he said, “they’re pretty fried out by now, and one night they start hearing voices. Like at a cocktail party. That’s what it sounds like, this big, swank, gook cocktail party somewhere out there in the fog. Music and chitchat and stuff. It’s crazy, I know, but they hear the champagne corks. They hear the actual martini glasses. Real hoity-toity, all very civilized, except this isn’t civilization. This is Nam.

“Anyway, the guys try to be cool. They just lie there and groove, but after a while they start hearing—you won’t believe this—they hear chamber music. They hear violins and cellos. They hear this terrific mama-san soprano. Then after a while they hear gook opera and a glee club and the Haiphong Boys Choir and a barbershop quartet and all kinds of funky chanting and Buddha-Buddha stuff. And the whole time, in the background, there’s still that cocktail party going on. All these different voices. Not human voices, though. Because it’s the mountains. Follow me? The rock—it’s talking. And the fog, too, and the grass and the goddamn mongooses. Everything talks. The trees talk politics, the monkeys talk religion. The whole country. Vietnam. The place talks. It talks. Understand? Nam—it truly talks.

“The guys can’t cope. They lose it. They get on the radio and report enemy movement—a whole army, they say—and they order up the firepower. They get arty and gunships. They call in air strikes. And I’ll tell you, they fuckin’ crash that cocktail party. All night long, they just smoke those mountains. They make jungle juice. They blow away trees and glee clubs and whatever else there is to blow away. Scorch time. They walk napalm up and down the ridges. They bring in the Cobras and F-4s, they use Willie Peter and HE and incendiaries. It’s all fire. They make those mountains burn.

The Smoke Signal, by Frederic Remington, 1905. Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

“Around dawn things finally get quiet. Like you never even heard quiet before. One of those real thick, real misty days—just clouds and fog, they’re off in this special zone—and the mountains are absolutely dead-flat silent. Like Brigadoon—pure vapor, you know? Everything’s all sucked up inside the fog. Not a single sound, except they still hear it.

“So they pack up and start humping. They head down the mountain, back to base camp, and when they get there they don’t say diddly. They don’t talk. Not a word, like they’re deaf and dumb. Later on this fat bird colonel comes up and asks what the hell happened out there. What’d they hear? Why all the ordnance? The man’s ragged out, he gets down tight on their case. I mean, they spent six trillion dollars on firepower, and this fat-ass colonel wants answers, he wants to know what the fuckin’ story is.

“But the guys don’t say zip. They just look at him for a while, sort of funny-like, sort of amazed, and the whole war is right there in that stare. It says everything you can’t ever say. It says, man, you got wax in your ears. It says, poor bastard, you’ll never know—wrong frequency—you don’t even want to hear this. Then they salute the fucker and walk away, because certain stories you don’t ever tell.”

You can tell a true war story by the way it never seems to end. Not then, not ever. Not when Mitchell Sanders stood up and moved off into the dark.

It all happened.

Even now, at this instant, I remember that yo-yo. In a way, I suppose, you had to be there, you had to hear it, but I could tell how desperately Sanders wanted me to believe him, his frustration at not quite getting the details right, not quite pinning down the final and definitive truth.

And I remember sitting at my foxhole that night, watching the shadows of Quang Ngai, thinking about the coming day and how we would cross the river and march west into the mountains, all the ways I might die, all the things I did not understand.

Late in the night Mitchell Sanders touched my shoulder. “Just came to me,” he whispered. “The moral, I mean. Nobody listens. Nobody hears nothin’. Like that fat-ass colonel. The politicians, all the civilian types. Your girlfriend. My girlfriend. Everybody’s sweet little virgin girlfriend. What they need is to go out on LP. The vapors, man. Trees and rocks—you got to listen to your enemy.”

And then again, in the morning, Sanders came up to me. The platoon was preparing to move out, checking weapons, going through all the rituals that preceded a day’s march. Already the lead squad had crossed the river and was filing off toward the west.

When action grows unprofitable, gather information; when information grows unprofitable, sleep.

—Ursula K. Le Guin, 1969“I got a confession to make,” Sanders said. “Last night, man, I had to make up a few things.”

“I know that.”

“The glee club. There wasn’t any glee club.”

“Right.”

“No opera.”

“Forget it, I understand.”

“Yeah, but listen, it’s still true. Those six guys, they heard wicked sound out there. They heard sound you just plain won’t believe. “

Sanders pulled on his rucksack, closed his eyes for a moment, and let out a short, throat-clearing sigh. I knew what was coming.

“All right,” I said, “what’s the moral?”

“Forget it.”

“No, go ahead.”

For a long while he was quiet, looking away, and the silence kept stretching out until it was almost embarrassing. Then he shrugged and gave me a stare that lasted all day.

“Hear that quiet, man?” he said. “That quiet—just listen. There’s your moral.”

In a true war story, if there’s a moral at all, it’s like the thread that makes the cloth. You can’t tease it out. You can’t extract the meaning without unraveling the deeper meaning. And in the end, really, there’s nothing much to say about a true war story, except maybe “Oh.”

True war stories do not generalize. They do not indulge in abstraction or analysis.

For example: war is hell. As a moral declaration the old truism seems perfectly true, and yet because it abstracts, because it generalizes, I can’t believe it with my stomach. Nothing turns inside.

It comes down to gut instinct. A true war story, if truly told, makes the stomach believe.

Tim O’Brien

From The Things They Carried. Both of O’Brien’s parents were involved in World War II; his father served in the Pacific and his mother in a division of the navy called Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service. Opposed to the Vietnam War, he received his draft notice shortly after graduating from Macalester College in 1968. He served in My Lai as an infantryman in 1969 and earned a Purple Heart before returning to the U.S. in 1970. While working for the Washington Post in 1973, he published his first book, If I Die in a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Ship Me Home.