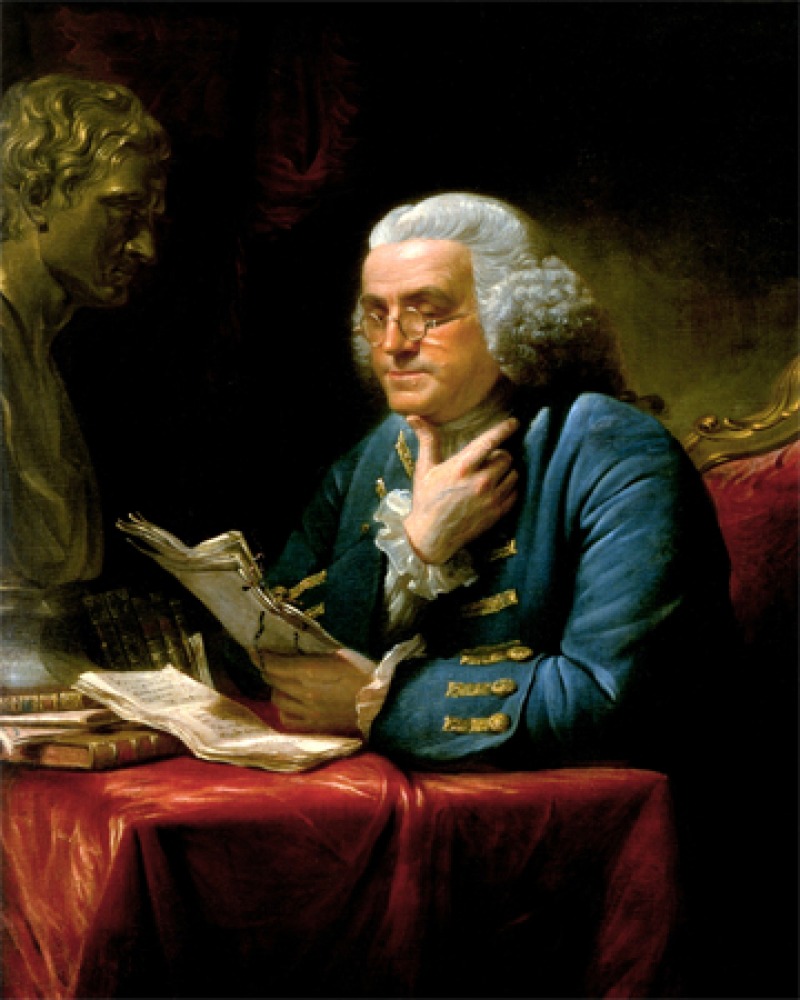

Benjamin Franklin

Journal of a Voyage,

1726

Journal of a Voyage,

Friday, July 22—Yesterday in the afternoon we left London and came to an anchor off Gravesend about eleven at night. I lay ashore all night and this morning took a walk up to the Windmill Hill, whence I had an agreeable prospect of the country for about twenty miles round, and two or three reaches of the river, with ships and boats sailing both up and down, and Tilbury Fort on the other side, which commands the river and passage to London. This Gravesend is a cursed biting place; the chief dependence of the people being the advantage they make of imposing upon strangers. If you buy anything of them and give half what they ask, you pay twice as much as the thing is worth. Thank God, we shall leave it tomorrow.

Saturday, July 23—This day we weighed anchor and fell down with the tide, there being little or no wind. In the afternoon we had a fresh gale, that brought us down to Margate, where we shall lie at anchor this night. Most of the passengers are very sick. Saw several porpoises, etc.

Sunday, July 24—This morning we weighed anchor, and coming to the Downs, we set our pilot ashore at Deal, and passed through. And now, while I write this, sitting upon the quarterdeck, I have, methinks, one of the pleasantest scenes in the world before me. It is a fine, clear day, and we are going away before the wind with an easy, pleasant gale. We have near fifteen sail of ships in sight, and I may say in company. On the left hand appears the coast of France at a distance, and on the right is the town and castle of Dover, with the green hills and chalky cliffs of England, to which we must now bid farewell. Albion, farewell!