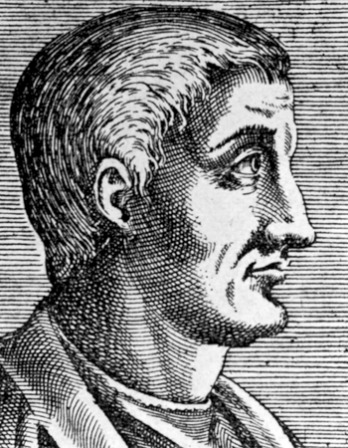

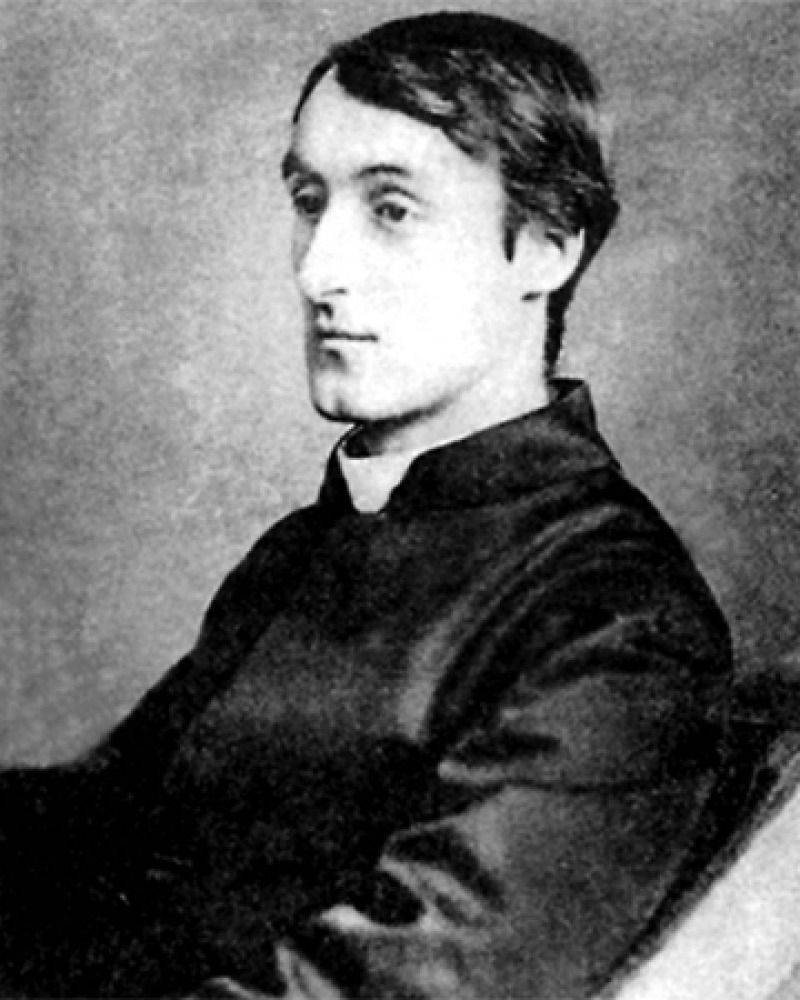

Gerard Manley Hopkins

“Spring and Fall,”

1880

“Spring and Fall,”

To a young child

Márgarét, áre you gríeving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

Leáves, líke the things of man, you

With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?

Ah! Ás the heart grows older

It will come to such sights colder

By and by, nor spare a sigh

Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie;

And yet you will weep and know why.

Now no matter, child, the name:

Sórrow’s spríngs áre the same.

Nor mouth had, no nor mind, expressed

What heart heard of, ghost guessed:

It ís the blight man was born for,

It is Margaret you mourn for.