People living deeply have no fear of death.

—Anaïs Nin, 1935Heads Above Water

“Many a man ought to have a bathtub larger than the boat which here rode upon the sea.”

None of them knew the color of the sky. Their eyes glanced level, and were fastened upon the waves that swept toward them.

These waves were of the hue of slate, save for the tops, which were of foaming white, and all of the men knew the colors of the sea. The horizon narrowed and widened, and dipped and rose, and at all times its edge was jagged with waves that seemed thrust up in points like rocks.

Many a man ought to have a bathtub larger than the boat which here rode upon the sea. These waves were most wrongfully and barbarously abrupt and tall, and each froth top was a problem in small-boat navigation.

The cook squatted in the bottom and looked with both eyes at the six inches of gunwale which separated him from the ocean. His sleeves were rolled over his fat forearms, and the two flaps of his unbuttoned vest dangled as he bent to bail out the boat. Often he said, “Gawd! That was a narrow clip.” As he remarked it, he invariably gazed eastward over the broken sea.

The oiler, steering with one of the two oars in the boat, sometimes raised himself suddenly to keep clear of water that swirled in over the stern. It was a thin little oar, and it seemed often ready to snap. The correspondent, pulling at the other oar, watched the waves and wondered why he was there.

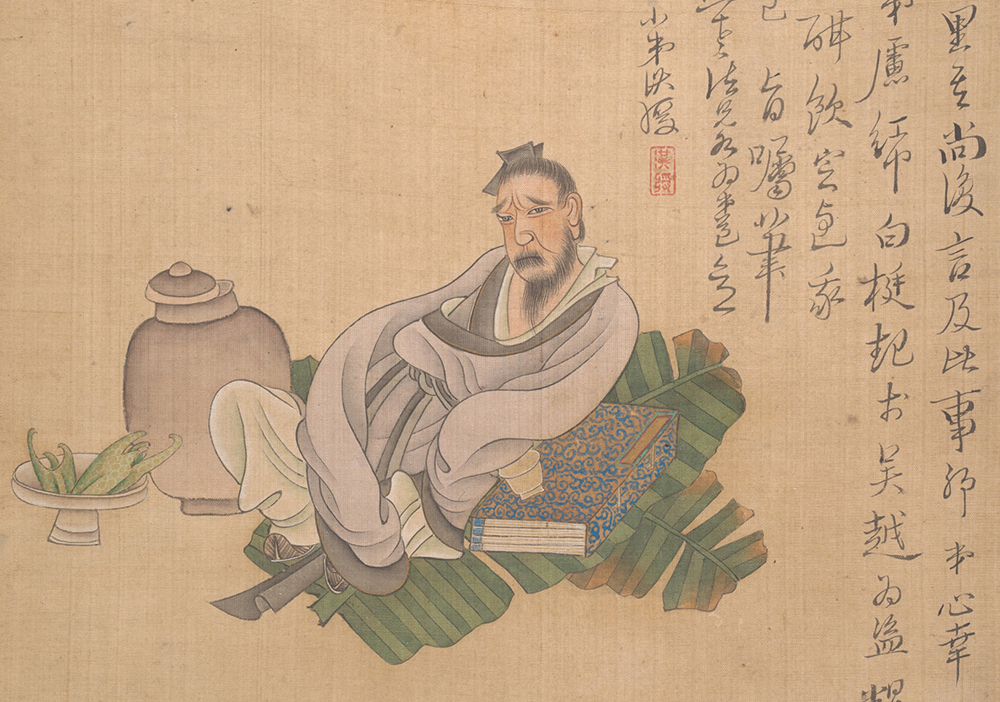

Self-portrait of Chen Hongshou as a dejected scholar (detail), 1627. Four years earlier, Chen’s first wife died and he failed the provincial examinations. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Wan-go H.C. Weng, 1999.

The injured captain, lying in the bow, was at this time buried in that profound dejection and indifference which comes, temporarily at least, to even the bravest and most enduring when, willy-nilly, the firm fails, the army loses, the ship goes down. The mind of the master of a vessel is rooted deep in the timbers of her, though he command for a day or a decade; and this captain had on him the stern impression of a scene in the grays of dawn of seven turned faces, and later a stump of a topmast with a white ball on it that slashed to and fro at the waves, went low and lower, and down. Thereafter there was something strange in his voice. Although steady, it was deep with mourning, and of a quality beyond oration or tears.

“Keep’er a little more south, Billie,” said he.

“A little more south, sir,” said the oiler in the stern.

A seat in this boat was not unlike a seat upon a bucking bronco, and by the same token, a bronco is not much smaller. The craft pranced and reared and plunged like an animal. As each wave came, and she rose for it, she seemed like a horse making at a fence outrageously high. The manner of her scramble over these walls of water is a mystic thing, and, moreover, at the top of them were ordinarily these problems in white water, the foam racing down from the summit of each wave, requiring a new leap, and a leap from the air. Then, after scornfully bumping a crest, she would slide and race and splash down a long incline and arrive bobbing and nodding in front of the next menace.

A singular disadvantage of the sea lies in the fact that, after successfully surmounting one wave, you discover that there is another behind it, just as important and just as nervously anxious to do something effective in the way of swamping boats. In a ten-foot dinghy one can get an idea of the resources of the sea in the line of waves that is not probable to the average experience, which is never at sea in a dinghy. As each slaty wall of water approached, it shut all else from the view of the men in the boat, and it was not difficult to imagine that this particular wave was the final outburst of the ocean, the last effort of the grim water. There was a terrible grace in the move of the waves, and they came in silence, save for the snarling of the crests.

In the wan light, the faces of the men must have been gray. Their eyes must have glinted in strange ways as they gazed steadily astern. Viewed from a balcony, the whole thing would, doubtless, have been weirdly picturesque. But the men in the boat had no time to see it, and if they had had leisure, there were other things to occupy their minds. The sun swung steadily up the sky, and they knew it was broad day because the color of the sea changed from slate to emerald green, streaked with amber lights, and the foam was like tumbling snow. The process of the breaking day was unknown to them. They were aware only of this effect upon the color of the waves that rolled toward them.

In disjointed sentences, the cook and the correspondent argued as to the difference between a lifesaving station and a house of refuge. The cook had said, “There’s a house of refuge just north of the Mosquito Inlet Light, and as soon as they see us, they’ll come off in their boat and pick us up.”

“As soon as who see us?” the correspondent said.

“The crew,” said the cook.

“Houses of refuge don’t have crews,” said the correspondent. “As I understand them, they are only places where clothes and grub are stored for the benefit of shipwrecked people. They don’t carry crews.”

“Oh yes, they do,” said the cook.

“No, they don’t,” said the correspondent.

“Well, we’re not there yet, anyhow,” said the oiler in the stern.

“Well,” said the cook, “perhaps it’s not a house of refuge that I’m thinking of as being near Mosquito Inlet Light. Perhaps it’s a lifesaving station.”

“We’re not there yet,” said the oiler in the stern.

As the boat bounced from the top of each wave, the wind tore through the hair of the hatless men, and as the craft plopped her stern down again, the spray slashed past them. The crest of each of these waves was a hill, from the top of which the men surveyed, for a moment, a broad tumultuous expanse, shining and wind riven. It was probably splendid. It was probably glorious, this play of the free sea, wild with lights of emerald and white and amber.

“Bully good thing it’s an onshore wind,” said the cook. “If not, where would we be? Wouldn’t have a show.”

“That’s right,” said the correspondent.

The busy oiler nodded his assent.

Then the captain, in the bow, chuckled in a way that expressed humor, contempt, tragedy, all in one. “Do you think we’ve got much of a show, now, boys?” said he.

Whereupon the three were silent, save for a trifle of hemming and hawing. To express any particular optimism at this time, they felt to be childish and stupid, but they all doubtless possessed this sense of the situation in their mind. A young man thinks doggedly at such times. On the other hand, the ethics of their condition was decidedly against any open suggestion of hopelessness. So they were silent.

“Oh well,” said the captain, soothing his children, “we’ll get ashore all right.”

But there was that in his tone which made them think, so the oiler quoth, “Yes! If this wind holds!”

The cook was bailing, “Yes! If we don’t catch hell in the surf.”

Stephen Crane

From “The Open Boat.” On New Year’s Eve 1896, while on assignment for a news syndicate, Crane left Jacksonville, Florida, on the SS Commodore, bound for Cuba. The steamboat, which was bearing guns and ammunition, sank shortly after leaving port. Crane and three crewmen spent thirty hours adrift in a ten-foot dinghy; all but one of them survived. A wreck found by marine archaeologists twelve miles off the Florida coast was confirmed in 2004 to be that of the Commodore.