Mr. Duke’s daughter, in her eighteenth year, fell into a total suppression of her monthly courses from a multitude of cares and passions of her mind, but without any symptom of the greensickness following upon it.

From which time her appetite began to abate, and her digestion to be bad; her flesh also began to be flaccid and loose, and her looks pale, with other symptoms usual in a universal consumption of the habit of the body. She was wont by her studying at night and continual poring upon books to expose herself both day and night to the injuries of the air, which was at that time extremely cold, not without some manifest prejudice to the system of her nerves. Loathing all sorts of medicaments, she wholly neglected the care of herself for two full years, till at last being brought to the last degree of consumption, and thereupon subject to frequent fainting fits, she applied herself to me for advice.

I do not remember that I did ever in all my practice see one that was conversant with the living so much wasted with the greatest degree of a consumption (like a skeleton, only clad with skin), yet there was no fever, but on the contrary a coldness of the whole body; no cough or difficulty of breathing; no looseness, or any other sign of a colliquation, or preternatural expense of the nutritious juices. Only her appetite was diminished, and her digestion uneasy, with fainting fits, which did frequently return upon her. Which symptoms I did endeavor to relieve by the outward application of aromatic bags, stomach plasters, bitter medicines, chalybeates, and juleps made of cephalic and antihysteric waters. Upon the use of which she seemed to be much better; but being quickly tired with medicines, she begged that the whole affair might be committed again to nature, whereupon, consuming every day more and more, she was after three months taken with a fainting fit and died.

From Phthisiologia; or, A Treatise of Consumptions. This account of anorexia nervosa is the earliest attested in English, though the term itself would not be introduced until 1873, in a paper by English physician William Withey Gull. Morton, a physician from Suffolk, became celebrated for his work on tuberculosis (then rampant in Europe), once remarking that he could not “sufficiently admire that anyone, at least after he comes to the flower of his youth, can die without a touch of consumption.”

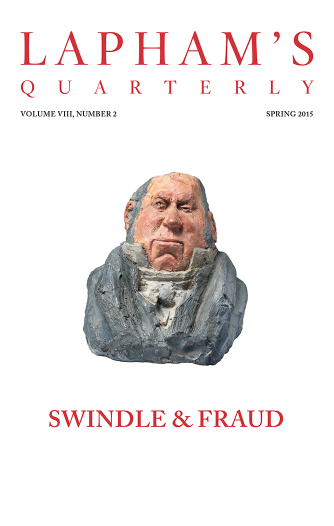

Back to Issue