My face looks like a wedding cake left out in the rain.

—W.H. Auden, 1967

Morning (detail) by Pierre Antoine Baudouin, c. 1760. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Ann Payne Blumenthal, 1943.

In the mid-eighteenth century, the term bureaucracy entered the world by way of French literature. The neologism was originally forged as a nonsense term to describe what its creator, political economist Vincent de Gournay, considered the ridiculous possibility of “rule by office,” or, more literally, “rule by a desk.” Gournay’s model followed the form of more serious governmental terms indicating “rule by the best” (aristocracy) and “rule by the people” (democracy). Yet bureaucracy quickly developed a nonsatirical life of its own once the French Revolution got under way. The Terror was, of course, infamously bureaucratic, with dossiers the way to denunciation, condemnation, and execution.

On July 2, 1789, as legend has it, a voice rang out from the interior of the Bastille into the street below: “They are killing prisoners in here!” Two weeks later, citizens stormed the Bastille, inaugurating the long and complex series of events that would constitute the French Revolution. The alleged yeller, one Donatien-Alphonse-François de Sade, had been removed to the insane asylum at Charenton ten days before the siege, thus having miraculously galvanized his potential liberators or murderers and evaded them. It is a singular piece of luck that Sade was not present for the storming, for it is likely that, descending upon the marquis’ luxuriously appointed cell, the sansculottes would have had some difficulty differentiating Sade from his oppressors, much less from their own.

As this series of apocryphal events intimates, the Marquis de Sade occupies an unusual place in French letters. He is at once the paradigmatic aesthete to end all aesthetes, a supreme materialist and spendthrift, an aristocrat determined to organize his life around complexly choreographed orgies (and the eccentrically appointed locations necessary for these performances), and an iconoclast, if not a revolutionary. Though the paper trail that emerges from his early life includes at least three accusations of flaying, stabbing, poisoning, and other unusual forms of physical and emotional abuse—leveled by prostitutes and other women poorly protected by the law—Sade has been held up as a beacon of sexual liberation during an era benighted by Christian repression and hypocrisy. Susan Sontag and Julia Kristeva have praised the freedom of his writing and thought. As the myth of his cry to action from within the Bastille indicates, Sade’s readers are willing, in spite of his title, to receive him as an anarchist hell-bent on upending the feudal order of his day.

But for all Sade’s aristocratic indulgence of peculiar whims and profligate spending on whips and whores, he is also one of the first major authors of what we might term modern bureaucratic literature. His writings are extraordinarily, pruriently concerned with acts that can be accomplished only by people working in groups who follow, in an orderly fashion, arbitrary rules and regulations. These secular constraints not only defy common sense but fly in the face of what we usually think of as basic respect for the sensations and lives of others. Thus another neologism: sadism. The writings of the Marquis de Sade describe dispassionate intimacy in the plural. In this sense, they foreshadow the social world of the contemporary office.

Cannibalism scene, color engraving from Grand Voyages, by Theodore de Bry, 1592. © Service Historique de la Marine, Vincennes / Bridgeman Images.

Like the word bureaucracy, sadism is a neologism that has taken on a life of its own. Today, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, sadism is an “enthusiasm for inflicting pain, suffering, or humiliation on others.” Yet Sade’s notion of dispassionate intimacy is quite particular. His sadism is less concerned with pleasure in the pain of others than with a lack of feeling regarding the pain of others. Though many of Sade’s writings describe characters who engage in cruel and murderous acts of sexual congress, few if any seem to enjoy the pain of others, no matter how necessary the mutilation of flesh to the act in question. Sade’s embodied economic processes, his sometimes rather less than mutually consenting coworkers, labor to produce orgasm—which is really just a route to apathy. After orgasm, Sade’s libertines are briefly freed from the confusing sensation of need. The libertine looks dispassionately down upon the flayed corpse in which he has just succeeded in ejaculating and experiences clarity. The corpse cannot, reasonably, be the object of affections or emotion; it holds no spell of either generosity or dependency over the Sadean character who has just made use of it. A corpse, even if nominally endowed with life, can inspire nothing other than apathy in the libertine. And apathy is the aesthetic mode that, for Sade, correlates with the best forms of agency, since it demonstrates the libertine’s freedom from Christian sympathy and its attendant hypocrisies. An absolutely liberated, absolutely impersonal pleasure testifies to the libertine’s refusal of insincere social bonds. “Virtue suffers the punishment of crime,” wrote Simon-Nicolas-Henri Linguet in 1771, “even as crime enjoys with impunity the pleasures that should be the rewards of virtue.” Sadean sex is, to inject a contemporary term, the fuck of the spreadsheet, in which all markers of identity and sentimentality are like the footlong dildo the eponymous libertine heroine of The History of Juliette uses to impale a nine-year-old girl: detachable, iterable, and sortable by size. Anyone can be a libertine, provided she or he is willing to be systematic.

The most famous of Sade’s narratives, 120 Days of Sodom, is also the most explicit about the Sadean protagonist or sadist. Here again liberation through apathy, rather than through cruelty or enjoyment, is key. The four friends who convene at Château de Silling for a four-month debauch are not so much interested in harming others as they are in orchestrating an experience that will be beyond anything they have previously enacted. This experience will, therefore, culminate in their absolute liberation from moral order. Drafted during Sade’s incarceration at the Bastille in microscript on a forty-foot roll of paper pieced together from smuggled scraps, 120 Days was a physical labor of desperation, passion, and personal and political rage, the composition of which was apparently accompanied by elaborate masturbation rituals. Sade never completed the manuscript, so we do not know what will happen to the libertines on day 120—but it seems to be a matter of little difference if they were to walk away from their fortress of horrors with plans to reconvene the following year or if the secluded castle were spontaneously engulfed in flames, taking all occupants to their deaths. (Manuscript notes suggest that sixteen people will survive the events at Silling and return to Paris, but who knows what, in a final draft, might have occurred.) Our own ambivalence regarding the book’s actual ending, which Sade sketches out in his notes as a series of coordinated imprisonments and executions, is not accidental. It results from Sade’s skillful cultivation of simultaneous prurient interest and utter apathy in the reader of 120 Days of Sodom. We are fascinated by the four libertine friends’ stats, by their personal deterioration or fortitude, by their ability to orgasm repeatedly or not at all, by the revolting details of body hair and the shapes of their buttocks. But beyond their appetites, appearances, and aristocratic titles, we know little of the friends save what they do in the fortress. And because what they do in the fortress is determined by a set of laws drawn up at the outset of their macabre vacation, plus narratives supplied by ancient procuresses invited expressly to narrate acts of debauchery, our psychological understanding of the four friends remains limited. We know that they are very rich, highly sexed, extraordinarily well organized, and thoroughly apathetic. Of the victims we know significantly less: they are young, beautiful, soft-skinned.

Within this desert of spiritual detail, one piece of familial backstory is supplied. At the opening of 120 Days, we learn that each of the friends has raped his own daughter and that each has married the unfortunate daughter of another one of the four friends. This arrangement guarantees that Christian marriage has been reimagined as an enterprise of debauchery. Yet this brief peek at a previous arrangement among the four provides a key to the meaning of other relentlessly formal coital permutations set up later on: 120 Days of Sodom is not a novel about the apathy of institutions and how they dehumanize and anonymize their members. It is not about marriage, unless we understand the four friends’ relationship as a kind of marriage. It is, rather, a novel about the apathy of coworking, a description of how individuals collaboratively create codes for behavior and imagine actionable scenarios in an enclosed space—i.e., office, another relative neologism derived from the Latin word for “obligation”—all the while guaranteeing that their actions will be impersonal. This is the sense in which 120 Days of Sodom can be considered an “office novel.” It is also, bizarrely, a comedy; it is the story of a highly successful office and how it works.

If, as in Tolstoy’s formulation, all successful offices are the same, what are the universal qualities of Sodom, LLC? What does this happy office have that other offices also share?

Hierarchy. The four friends form an executive committee, which is overseen by the four procuresses, four duennas, and four storytellers, who operate like a toothless board of directors. Beneath the four friends and their advisers are eight individuals titled “fuckers” whose professional function is not mysterious. Forming the ranks of junior staff are the four friends’ four unlucky daughter-wives and a group of sixteen children who are essentially sacrificial victims, aka interns—or, in a more perverse reading, the very 8½-x-11 multiuse acid-free paper on which the workplace discourse is pitilessly inscribed. There is no mobility within this hierarchy. A kitchen staff of three is exempt from the orgies so that it may concentrate on preparing food. There is also a scullery staff of three, all apparently murdered at the novel’s close according to Sade’s final notes.

Accounting. Sade’s own hand appears throughout the manuscript to count characters, particularly if any have been killed off, and to tally activities. At the close of the manuscript, he instructs himself to keep an account of the particular passions of his four central protagonists, “as, for example, the hell libertine,” though what he means by this is not entirely clear; it appears that he was separated from the manuscript before he was able to make good on this plan. This dispassionate accounting seems to require that the author catalogue the preferences of the four libertines so that each friend is scientifically differentiated. Elsewhere in his notes, Sade complains of his own tendency toward confusion and repetition, an imperfection he planned to correct with a more stringent accounting.

Purpose-built office space. The Château de Silling has numerous chambers with diverse designated functions. For example, everyone is required to defecate in the castle’s chapel. There are bedrooms for sleeping, a dungeon for torturing and murdering, a stage for communicating tales of debauchery. There are no exits; these have been walled off at the novel’s start, accessibility being a liability rather than an asset as far as the libertines’ place of business is concerned.

Production schedule. Each day at the Château de Silling unspools in a regular way. All present arise at ten AM, and debauchery and dining occur at fixed intervals until two AM. There are designated months for certain activities, as well as designated apparel. All present are made aware of their hourly tasks, but only the libertines know of the torture and slaughter with which the four-month fiscal year will end.

Catering. Delicious meals are provided in a timely fashion by dedicated cooks.

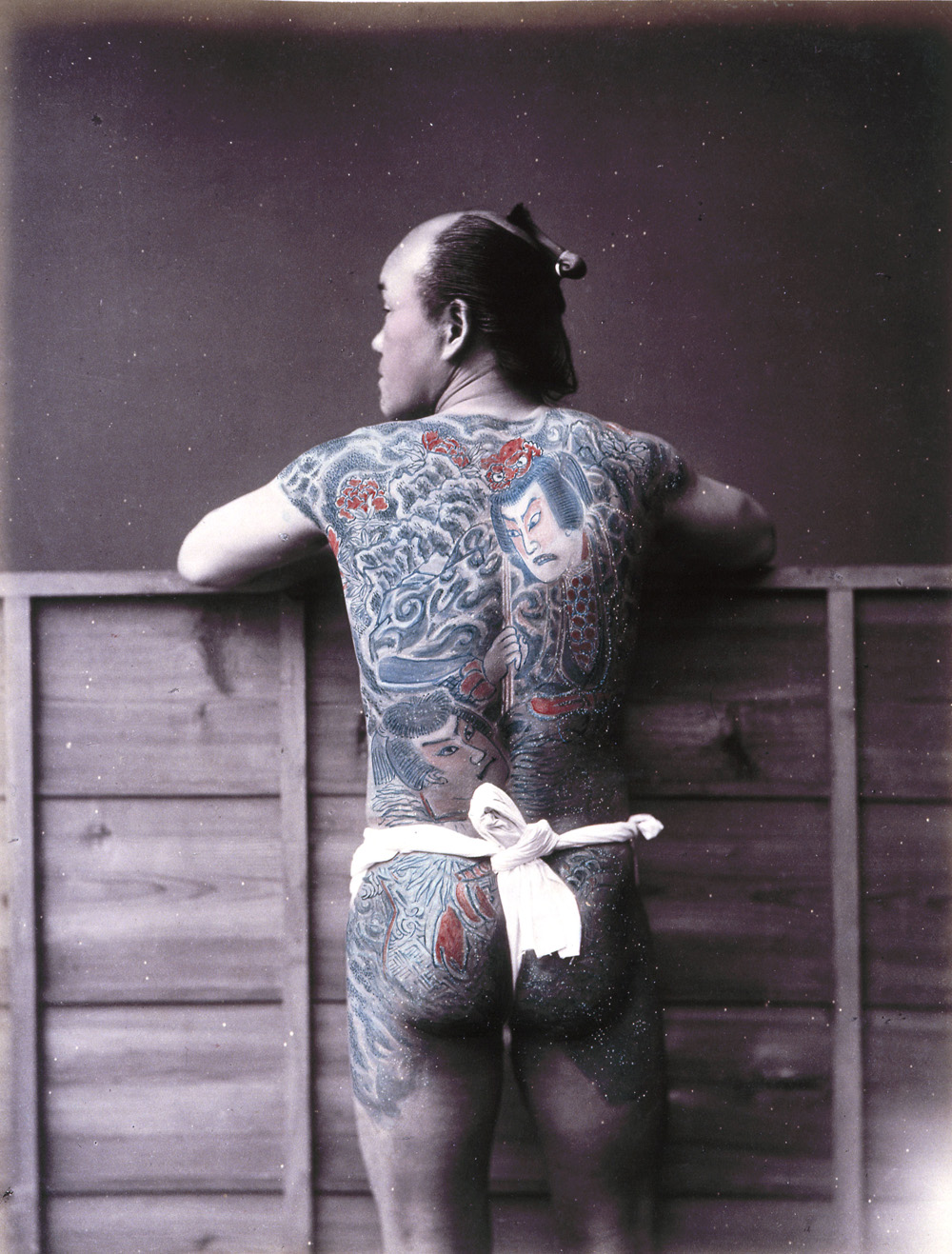

Tattooed Japanese man, c. 1880. Hand-colored photograph by Kusakabe Kimbei. © Kharbine-Tapabor / The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

Bonuses. There is an unusual amount of eating of shit. In some psychoanalytic readings of the practice of coprophilia, excrement represents money. Certainly scat functions as a rarity in everyday sexual economies. At Château de Silling it is plentiful.

Dispassionate intimacy. All sex acts are preordained and coordinated by statutory schedule. The victims of the libertines cannot choose whether or not to have sex, but even the libertines are not free to choose when, whom, or how they fuck. The only emotional reaction manifested by the libertines is that of impatience, inspired by delays in sexual activity worked into the schedule set at the beginning of the novel. These delays have a speculative function. They increase the libertines’ passion through denial, which increases the yield on passion’s principal, as it were. Such delays are not directed at any particular libertine. They are impersonal, general, and purely pragmatic.

Office work sets into tension, in close quarters, the ambitions of the individual and the destiny of the group. Office workers rub elbows with one another and gather at the water (or kombucha) cooler, rolling chairs collide and become entangled, sweaty softball tournaments are organized. It is possible that the success of the individual can become the success of the group, but it is more likely that in order for an office to succeed, individuality must be undermined, in that it must always directly serve the plural. Here is a rationale for the current vogue for open-plan work spaces, in which one has little privacy unless urinating, defecating, or making coffee. The open-plan-office worker must progress from a state of hyperconsciousness of the effect of her fleshly presence on her coworkers to total numbness in order to get any work done. In such work spaces, the sensitive are likely to spend their days endeavoring to stop unconsciously fidgeting or touching their faces or hair. Open-plan offices also stymie the unusually creative and independent, reducing them into collaborators. Management likes this. Accountability and credit can circulate in offices and even temporarily land, but there should be no authors in offices, only positions. Meanwhile, offices are not just places. Offices are not merely locations, nor are they particularly egalitarian. There are “office politics.” The office has a will of its own, yet, paradoxically, it is not exactly collective.

Setting aside for a moment the annoying behavior to which we must become inured if we are to survive the office (inane chats, baffling email communications, multipage budgets), we must also learn to cherish less our personal specificity. This soft injunction to conform often has a funny way of meaning that we must also become inured to our colleagues’ specific personalities. We do not fully choose or even desire our coworkers, no matter how intentional or progressive the workplace. At the office, we need one another to fulfill certain tasks by means of certain skills. We have less need, inevitably, of our coworkers’ personal histories, the deep reasons why they are the way they are or need whatever is needed. Nor do we have much use for our coworkers’ bodies, in all their ample particularity. We must, with our coworkers, develop forms of dependency and attachment that are risible and fungible, but not too risible and not too fungible. The legend emblazoned above most office doors should be “Try Not to Harm One Another When Convenient but, Above All, Don’t Love One Another.” Far worse than insulting one’s office mate or stepping on a colleague’s toe would be to recognize her or him as one’s soul mate. In such a scenario, all work would cease. We, like Sade’s libertines, require a modicum of impersonality, if not an actual series of statutes or rotating cast of narrating hags, in order to interact effectively with our coworkers. We tersely sign our emails “Best,” but what does this really mean? How can we wish for the best on behalf of someone we—purposefully—barely know? And yet there is no more appropriate or versatile send-off. The polite, efficient apathy implied by “Best” is one of the greatest office supplies known to the contemporary world; it should be bottled and sold in bulk at Staples—which, perhaps, in some sense it already is.

Did Sade know he was writing about office life? Did he intuit that the neoclassic return of republican forms of government to the West would also bring new administrative cultures, new ways of dispersing agency within groups, new levels of mediation and organization of bodies by form and file not even imagined by the church? For Sade, the project of “being with” is a notion not as fraught as it is aggressively simplified. His erotic project, like Kant’s ethical project, is a reasonable means of removing hypocrisy and contingency from social interactions—or, perhaps, of removing hypocrisy by way of removing contingency. (Jacques Lacan, for one, was so taken by the marquis’ infallible logic that he placed Sade’s texts in dialogue with Kant’s writings on reason and ethics to contextualize modernity’s path to Freud.) Sade seems to dream of a sexual relationship in which choice, chance, personal dependency, and the existence of a consenting other have been removed. As things stand, there is too much contingency and complexity in sex for Sade’s taste. Indeed, according to Sade, sex can never be too orderly or too public. It is this valence of his thought that seems overwhelmingly applicable to the contemporary office, if not to contemporary social life overall. We suffer still from an excess of contingency when it comes to others. Too much is possible, particularly in light of the “death” of the Catholic god against whom Sade railed. In major metropolitan areas—hives of office life—everything is permitted, and too many bodies are way too near to hand.

The German systems theorist Niklas Luhmann wrote a lecture on love in the summer of 1969 in which he argues that love is an important form of mediation, a solution to the problem of excessive contingency in republican social life. According to Luhmann, love allows us to simplify our social lives in a way that is, counterintuitively, not reductionist, since love depends on our individuality in order to function. Luhmann argues for the exceptionality of love, maintaining that “other media of communication can take the place of love to only a very limited extent, just as love can not take the place of truth or power or money without limitations.” Compare Luhmann’s solution to Sade’s: the latter removes love altogether while the former describes love as a logical necessity. Perhaps this is why Sade’s descriptions of human interactions seem so much more applicable to office work than to personal life. While the personal continues to dominate contemporary culture, it is difficult for those of us who cherish our individuality, as well as our privacy, to take Sade entirely seriously. We should also be just a bit afraid of him.

Flesh was the reason why oil painting was invented.

—Willem de Kooning, 1949It is crucial to mention that 120 Days of Sodom is, in spite of the copious violence and elaborate intercourse, one of the most boring novels of all time, particularly if read from beginning to end. One might, at some point in its pages, prefer to take up with an ATM receipt or an end-user license agreement. The novel expresses apathetic joys that are less reminiscent of the aesthetics of the snuff film—a genre that, pace ISIS, is almost always determined to have been faked—than the horrors of petty administrative perfections, callous email exchanges, and endless insurance forms. The faint pleasure of office culture is merely the anodyne pleasure of any coworker, scrolling through email before she heads out to the next meeting. It might seem like perversity to describe it as such, but take a closer look: herein lies your pleasure. For today, everyone is a libertine.