Flesh was the reason why oil painting was invented.

—Willem de Kooning, 1949Reinventing Sex

The Oneida Community challenged American standards of sex and marriage.

By Peter von Ziegesar

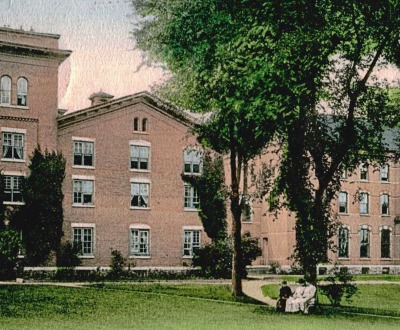

Oneida Community Main Building, c. 1907.

We are wonderful musical instruments; made to give and receive great pleasure in love.

—John Humphrey Noyes

In April a year ago I drove north from New York City to visit the Oneida Community Mansion House. It’s certainly one of the most curious museums in America. A redbrick edifice weighed down with cornices, dentils, towers, porticoes, gables, and other oddments of the Victorian architectural imagination, the Mansion House is fronted by a curved drive and sloping lawn, and lacks only a polite scattering of whitewashed Appalachian chairs to complete the picture of a prosperous Victorian resort, or perhaps a genteel insane asylum. The 93,000-square-foot Mansion House was built between 1861 and 1878 to accommodate three hundred men and women united in “complex” marriage, an arrangement invented by the Oneida founder, a defrocked minister named John Humphrey Noyes. Members were encouraged to have sex freely with other members, the only proscription being that they avoid forming “special love,” their term for a monogamous relationship.

The Oneida mansion was designed for the pursuit of love and the encouragement of sexual pleasure. Intercourse, according to Noyes, should be an “innocent and useful communion,” a “joyful act of fellowship,” and a “purely social affair,” comparable to a stroll in the park, a conversation, or a dance, differing from these pursuits only in its superior intensity and beauty. In a society trained to Noyes’ principles, intercourse would take its place among the fine arts. Indeed, it would rank above music, painting, and sculpture, for it combined “the charms and benefits of them all.”

Noyes came from generations of New England aristocracy. His father, John, served a term in Congress as a Vermont representative, and President Rutherford B. Hayes was his first cousin. Portraits on the walls depict a short man with a tight collar, bulging forehead, and determined chin. What these portraits don’t reveal is what his son Theodore, a Yale-educated doctor, would ruefully attest: that his father had been “a man of quite extraordinary attractiveness to women.” Perhaps no leader since Genghis Khan has surrounded himself with such carnal combinations of spirit and sexuality. That a woman might revel in the flesh of man, and man in the flesh of woman, didn’t bother the minister. And he didn’t care if any of the couplings he presided over were legitimized by civil marriage. Noyes was inspired by perfectionism, a distinctly underground Protestant sect that had adopted the almost Buddhist view that a man could reach spiritual perfection before his death, and when he did so the normal laws of man and religion would no longer apply. Noyes could often be seen through the open door of his tower bedroom reading from his favorite work of erotic literature, the King James Bible. The scriptures were replete with lurid couplings of all kinds, and often equated religious grace with the delights of sexual intercourse. They gave ample proof, to Noyes at least, that his most far-out theories about group marriage, birth control, incest, adolescent sexuality, and the virtue of sexual pleasure were divinely sanctioned.

Upon entering the Mansion House, I passed quickly through bookstore and lobby and into the marrow of the museum. So great is their reverence for the building that, even now, 125 years after the community’s demise, a handful of descendants still live here in apartments set aside for their use. I encountered a few of them walking with difficulty down the corridors that their ancestors had trod so confidently, their heads blessed by halos of white hair that flared in the overhead lights as they passed.

On the second floor I found the reading room, a tall, cool chamber with a wraparound balcony surrounded by a balustrade. On the shelves were bound copies of the popular literary magazines of the day, Harper’s Monthly, Scribner’s, and McClure’s. Oneidans prided themselves on keeping up with the times, and many from the second generation attended Yale and Harvard or the Berklee College of Music. Oneida may have been a cult, but it had no intention of becoming an isolated one. The most distinguished feature of the reading room is a series of small staterooms modeled after those on a steamboat, running around the walls and upstairs in a kind of porch. In these rooms members of the community would meet for an hour or so of intercourse, which they termed “love interviews,” before going off their separate ways to bed. Any woman who wished to have sex with a particular man simply asked through an emissary, and a man who wished to have sex with a woman did the same. The main rule for a “love interview” was that it should be kept short, as Noyes believed it “an excellent rule to leave the table while the appetite is still good.”

Oneida’s success was primarily due to the thrift, genius, and enterprise of its members. In other parts of the museum I viewed bear traps, silk skeins, silverware sets, and precision-engineered airplane parts manufactured by Oneidans. Ralph Waldo Emerson’s proverbial “better mousetrap” was invented at Oneida, and the Victor mousetrap company, which began there, is still in business today. So is the Oneida silverware company, now an international concern, which also started at the Oneida Community—I had passed its squat, castle-like headquarters on the way to the Mansion House. Another innovation, it’s said, was the lazy Susan, the centerpiece of many a dining-room table.

Fishing for Souls (detail), by Adriaen van de Venne, 1614. © Rijksmuseum.

But the glue that held the Oneida Community together and made the love interviews possible was Noyes’ invention of a tantric-like birth-control technique, male continence, which involved the male learning to withhold ejaculation during intercourse. In the early years of their marriage, Noyes’ wife, Harriet, suffered five painful pregnancies, only one of which produced a child—the rest were miscarriages. Noyes was a gentle, caring man, and his first thought was that he must give up having sex with his wife forever, and if that proved impossible, to live apart from her. He greatly enjoyed the pleasures of the marriage bed, however, so he began to hunt for ways to avoid unwanted pregnancy. He rejected condoms, those “tricks of the French voluptuaries,” and rightly banned leaving children out on the hillside as barbarous, though advocated by his favorite philosopher, Plato.

Noyes had a methodical mind. He was in many ways the lawyer he’d trained to be before he quit to become a minister. He noticed that “on the whole, the sweetest and noblest period of intercourse with woman” was at the very beginning, “that first moment of simple presence,” before the “muscular exercise” began. Certainly “every man who has had good sexual experience” would agree with him about that, he thought. What if he stopped at that point, and allowed himself to be content with that “simple presence,” savoring the moment without trying to force a crisis? “Would there be any harm?”

And now Noyes reasoned further. Suppose a man “knowing his own power and limits” should choose not only to enjoy the simple presence, but also the “reciprocal motions,” stopping short of the “final crisis” of ejaculation? Again he asked himself, “Would there be any harm?”

He created a mental picture of the act of intercourse in terms of a skillful boatman rowing on a wide river. Calm ripples spread out all around him, perhaps causing his skiff to rock a bit. His ears could hear the roar of a waterfall downstream, but for now this was not a threat. As long as the oarsman remained in the shallows he could ply his oar with ease and pleasure as long as he wished.

Farther down, though, where the river narrowed, he would enter a set of rapids. But to the skilled boatman the rough waves gave only more pleasure. He could pull and push against the tossing white water, dodging here and there, but the boat would remain safe. Even in the rapids he could dally without danger, enjoying his skill and the heady sensations of rocking and speed.

If Noyes continued downriver, he reasoned, he’d reach a point where he would have to struggle hard with the current or lose control of his craft and plunge over the falls. This would be climax. At this point, Noyes thought, “the skillful boatman may choose.” If his intentions are “propagative,” that is, to produce a child, then so be it: he may as well steer directly for the falls. If “amative” intercourse was his goal, that is, intercourse solely for pleasure and companionship, he was confident that prudence and experience would teach the oarsman how to stay far enough from the falls to get maximum pleasure without the danger of passing the point of no return.

Having brought his thought experiment to its logical end, Noyes decided to try his idea with his wife, Harriet. To his surprise, he found that the “self-control which it requires is not difficult; also that my enjoyment was increased; also that my wife’s experience was very satisfactory, as it had never been before; also that we had escaped the horrors and the fear of involuntary propagation.”

By “very satisfactory” Noyes almost certainly meant that his wife had experienced an orgasm for the first time. It can be intensely erotic to be with a woman who is having an orgasm, even at the cost of not having one yourself. Noyes’ method wasn’t just a primitive form of contraception, although it was effective at that. It transformed the sexual experience for both Victorian men and women. It prolonged and magnified the act of intercourse and promoted a deeper connection between partners, while putting male gratification on the back burner. It placed women’s pleasure and orgasm at the forefront at a time when the scientific establishment had all but denied its existence. Finally, it allowed men and women to choose their partners free from the bonds of monogamous marriage.

I’m at an age when my back goes out more than I do.

—Phyllis Diller, 1981How was intercourse accomplished using Noyes’ innovation? In the 1920s, long after the Oneida Community had ceased to be, a sex research pioneer named Robert Latou Dickinson came to the Mansion House to discover exactly that. Dickinson was fascinated with the variety of ways people could make love. Decades before Alfred Kinsey made a habit of taking notes on the erotic lives of everyone he met, Dickinson jotted down thousands of sexual histories. He found an aging grandniece of the founder, a physician named Hilda Herrick Noyes, who was happy to offer details. A bout of amative intercourse would last for an hour or more, she remembered, and the women were particularly happy at the “long play.” Typically, during a “love interview” a woman would lie on her side with one leg cocked while the man entered her from behind. Holding her very much as he might hold a cello, he’d reach his hand around to the front and manipulate her to a climax. At the same time, he refrained from having an orgasm himself. Thus, amative intercourse involved coitus, but the primary stimulation was by hand. The male’s assigned role was as a skilled musician who received his pleasure through the mastery of his instrument and through the vicarious enjoyment of the pleasures he was instilling. Noyes thought the connection profound and spiritual. A follower of Franz Mesmer, the doctor who sometimes caused followers to go into mass orgasms by hooking them up to enormous batteries, Noyes believed sexual intercourse was nothing less than “the interchange of magnetic influences, or conversation of spirits, through the medium of that conjunction.”

To hold a woman closely, flesh to flesh, to feel her pulse and breathing rise, to hear her exhalations and know that she has surrendered to your will, to set off the final detonation with the touch of your finger—these are primarily masculine concerns. But consider this: the women in the Oneida Community were liberated as few Victorian women were. They wore their hair in ambisexual bobs, a style that wasn’t to become popular in the rest of America until the 1920s. They wore long pants or “pantaloons” under their skirts that allowed them to labor alongside men at any job. And they did work—such as editing the community newspaper—that few women of their times were allowed. They were encouraged to be sexual equals, and the children who were born were raised by the community as a whole in nurseries that were staffed as much by men as by women.

Although at Oneida society was highly structured, there’s ample evidence that young and old took full advantage of their sexual freedom. A reasonably popular young woman like Tirzah Miller, Noyes’ niece and favorite lover, might have intercourse two or three times a week and change partners one or two times a month, or more often if she wished.

Eventually I arrived at the large upstairs meeting hall and took a seat in the gloom on one of the long Shaker-like benches. Before me was a tilted platform upon which Oneida residents had once staged entertainments and concerts. The meeting hall may have been set for yet another use. Noyes had been so eager to spread the word about his discoveries that he’d allowed a railroad spur from the nearest town to terminate at the bottom of the Mansion House front lawn. From its cars as many as 1,500 tourists per day would step out. They came to buy traps, canned peaches, and other handiwork; to marvel at the laughing children as they ran to and from school; to see the hard muscles in the arms of the men, who despite years of ejaculatory self-denial were clear-eyed and healthy. But most of all, they came to ogle at the red cheeks and happy smiles of the women, who had partaken of the forbidden fruit of pleasure and could sleep with whichever men they pleased. As dusk fell, tourists were invited to share a meal in the vast dining hall and view musical performances and dramatic plays the talented communards put on the stage of the meeting hall.

Girls in bikini-like outfits playing a ball game, Roman mosaic, Villa Romana del Casale, Sicily, c. 300. © Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina, Sicily / Bildarchiv Steffens / Bridgeman Images.

Although there’s no evidence Noyes ever went through with this idea, he had planned to make public demonstrations of Oneidan-style amative intercourse on that stage. “We shall never reach heaven until we have conquered shame and can make it a beautiful exhibition,” he confided. He’d thought out the program in some detail. A couple would be chosen from the audience. They would go onstage, where a couch would be on hand, there to disrobe, and then dance and perform other “evolutions” until the man was ready. Such a live demonstration, he thought, would purify all who viewed it, and also “give pleasure to a great many of the older people who now have nothing to do with the matter.” Sitting on my hard wooden bench, I tried to imagine it. Would one be permitted to cry “Hear! Hear!” or perhaps “Encore!” after a stirring performance?

Was the Oneida Community just a oneoff, a freak twist in our nation’s peculiar history? The British novelist Aldous Huxley thought not. Huxley had learned about John Humphrey Noyes and male continence in the 1920s on his first visit to America and remained an enthusiastic fan all of his life. The Oneida Community inspired his last book, Island, about a utopian tropical paradise whose sexually liberated inhabitants practiced intercourse just as the Oneidans did. In every culture and time, he speculated, there has always been a small but energized minority of men and women who deliberately avoided conventional orgasm in order to lengthen and broaden their sexual experience. Huxley attached a strange untitled essay to his book Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow that listed other places in history in which “bodily union without orgasm” had been practiced. He mentioned Tantric sexual ritual, the early Gnostics, a heretical medieval Flemish cult called the Adamites, and another medieval group, known as the Cathars, that thrived in northern Italy and southern France, as well as the Romans. In none of these places, Huxley noted, had there been any attempt to throttle sexual pleasure. Just the opposite. Men and women had learned to control their orgasmic states in order to enhance and extend them (although the desire to stem pregnancy certainly played a role). Since religion in those times was less separable from everyday life than it is now, and because sexual feelings are so far beyond the other pleasures one normally experiences, that purest sense of ecstasy and oneness one received from stretching out and even indefinitely delaying orgasm was considered identical to religious ecstasy. Huxley also quoted a passage by D.H. Lawrence—in which his heroine rejects “the white ecstasy of frictional satisfaction” with her lover for something else, “dark and untellable,” in which she gushes like a fountain “with noiseless soft power”—to show that proto-orgasmic states could occur in England, at least among a sexual elite.

O flesh, flesh, how art thou fishified!

—William Shakespeare, 1596Noyes was well aware that his program of a social order built around sexual pleasure had the potential to shake the world. In fact, that was his intention: to tear down the old and rebuild anew along what William Blake had called the “lineaments of gratified desire.” Generations of radicals, mystics, progressive Catholics, feminists, and libertines were to pass Noyes’ ideas on orgasm control from hand to hand in a sexual underground economy that would parallel the visible “moral” society and stretch into and beyond the twentieth century. When the pill, the sexual revolution, and the women’s liberation movement arrived in the 1960s, a good part of their DNA was derived from Oneida. Even today a burgeoning “slow sex” or “expanded orgasm” movement in California appears to have been directly inspired by Noyes’ sexual amativeness, thanks to a shadowy figure in the 1960s commune movement, Victor Baranco, also known as the “Thug Buddha.”

Baranco was of a type that was to become increasingly familiar in countercultural circles, a charismatic leader who invented his own religious precepts as he went along and incorporated sex at the center of his belief system. A former appliance salesman and the son of a wellknown San Francisco jazz musician, Baranco began buying dilapidated buildings and filling them with followers, whom he called “marks,” a carnival term for easy prey. His revelation occurred while shooting poker chips off the fence of his backyard in suburban Lafayette, outside Oakland. The revelation was of perfection—God’s and humankind’s perfection—that paradise could be found on earth and did not need to be sought in heaven. It seems likely that Baranco had simply stumbled upon the perfectionism of John Humphrey Noyes while seeking practical advice on how to run the twenty or so communal homes he owned. (When I asked members of his surviving Lafayette Morehouse commune whether Baranco had modeled himself on Noyes, they only repeated their leader’s oft-stated boast that he’d “never had an original idea in his life.”)

Cobbled with the epiphany was a sexual technique he called “deliberate orgasm,” or “DO-dating” (as in “do”-ing a woman), which involved manually stimulating a woman or man to the edge of orgasm until he or she reached an ecstatic state, similar to what Huxley had called “bodily union without orgasm,” the magnetic interchange of the Oneidans. Baranco came to regard his sexual research as the center of his enterprises. In the 1970s, he legally incorporated his flagship Morehouse commune as a state-accredited university, and in following decades trained thousands in the techniques of ecstatic orgasm control. From 1976 on he began offering public demonstrations of “a women having a three-hour orgasm,” thus fulfilling Noyes’ dream of turning amative intercourse into a “beautiful exhibition.” Reportedly, at these demonstrations, “students sometimes passed out, fell out of chairs, and pictures fell off walls.”

Noyes kept his communistic utopian community humming in relative harmony for a full generation, long enough so that the children of children were being introduced—at puberty—into the ways and means of sexual amativeness. There were bumps on the road to sexual freedom, as can well be imagined—tempests, piques, pregnancies, infatuations, broken hearts, minor rebellions against Noyes’ paternalistic authority, and midnight races down a hallway after an “accident” to get a syringe. Some Oneidan practices would not be tolerated today, such as the doctrine of “ascending fellowship,” in which young women were almost powerless to turn down requests for sex by middle-aged men of the inner circle—with Noyes himself often claiming the right to be “first husband”—and the practice of keeping mothers from children toward whom they showed too much “sticky” affection. But men and women were for the most part content with their relations. The image of the hedonist mansion house devoted to free love was to have amazing durability in the American imagination.

Eventually, the Oneida Community fell of its own weight. Noyes grew old and his sexual allure faded. A contributing factor was his ill-advised late venture into eugenics. As he matched men and women for procreation, often against their wills, he stirred up needless anguish, prompting his usually loyal niece Tirzah to ask her diary in despair, “Oh! Is he a crazy enthusiast who is just experimenting on human beings?” Perhaps sensing weakness gripping the community, in 1879 a coalition of ministers assembled to have Noyes arrested for sex with minors. He fled to Canada and remained there for the rest of his life, instructing his followers to reinstate monogamous marriage and transform their home into a stockholding corporation. Noyes remained proud of his accomplishments at Oneida, however. Years later he would write, “We made a raid into an unknown country, charted it, and returned without the loss of a man, woman, or child.”