The human body is the best picture of the human soul.

—Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1947

Venus and the Lute Player, by Titian, c. 1570. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Munsey Fund, 1936.

Conceived in pleasure and begotten in pain, the human animal is born naked like all other beasts. Much of the history of ideas about our condition is devoted to puzzling out the contrasts between the brutish constraints of our embodiment and our seemingly disembodied capacity to think, which projects us into abstract realms, away from our mortal, fragile, messy bodies. It is not enough that we can create mathematics, music, physics, and writing, in which bodily needs are silenced and sometimes transcended; we must also wonder about this very capacity. We are animals at once conscious, aware of finitude, and locked into corruptible flesh.

The word flesh conjures the potency of sexual desire and the bitterness of decrepitude and finitude, the one limiting the other, in the eternal dance of Eros and Thanatos. Flesh is what Titian’s luminous, erotic nudes celebrate, but also what Lucian Freud’s thick paint unforgivingly depicts as garish. It is the miraculously transformed marble of the Greco-Romans, Michelangelo, Bernini, and Rodin. It is at the center of the aestheticized and grotesque sexuality of Edo-era Japanese prints and of the nightmare visions of contemporary horror movies. It is the sensuous mass of fat and muscle painted by Rubens, but also the carcasses lovingly depicted by Chardin. Flesh conjures skin both as smooth cover behind which entrails hide and as those actual entrails, desirable as food for carnivores, for flesh is also meat.

The word body conjures none of this; the body is the observable structure of a living being, which is dressed for social existence and undressed for general care. Bodies may figure in a landscape as exempla, like those by Poussin, who was good at painting the skin color of his expressively gesturing figurines but did not manifest much interest in what was beneath the skin. Bodies are part of a composition, determined by external conditions, by clothes, by measurements, by the gazes of ourselves and others. We treat our bodies as an “it” and not quite identical with the self.

The state of flesh fluctuates from glorious pleasure to excruciating pain. When we die, our flesh disintegrates. As physical creatures, humans are at once beautiful and repulsive to one another—lovely skin enveloping innards unlovely to all except the doctors whose vocation it is to know their byways. Our being depends on physiological processes invisible to the eye, at once fascinating and terrifying in their potency. We are always potentially medical patients, teetering just this side of biological viability.

The enraging recognition of our imperfect, brittle embodiment has contrasted, for much of human history, with an incorruptible and immaterial sphere. Attached to the awareness of our biology, we have imagined a universe untouched by the limiting conditions of our flesh and posited laws that enable life to function according to this imagined realm.

In the West, and specifically within the Christian tradition that has shaped it to a large extent, there is a profoundly examined strand of thought about the status of flesh as inferior to that of the mind. This idea relies on dualism: the separation of the realms of flesh and mind. The dualist narrative in the West has its roots in ancient Greece, in the psychology envisioned by Plato and developed by Aristotle, and conceives of a hierarchical, divided soul—a higher order and a lower order. Reason was in touch with the cosmic order, above the disorderly passions and disruptive bodily appetites that humans shared with other living creatures. Both Greek philosophers’ schemes percolated into Christian doctrine, first by way of Augustine, later through Thomas Aquinas, who reinterpreted Aristotle for Christianity. The rational soul, unique to humans, was located in the brain. The sensitive soul, shared by humans and animals, was in the heart. And the appetitive soul, which ensured nutrition and reproduction, was in the liver. For Aristotle and the scholastic psychology that followed, the three organs were connected, sustaining conscious, sentient life.

Augustine, the inspired Church father, begins his Confessions as a fourth-century convert to the then-new religion as he grows aware of the sinful nature of the sensuality and unbridled sexuality he experienced in his youth. Spiritual enlightenment, for Augustine, was a function of the domination of the body’s urges. The body was capable of disobeying the spirit’s entreaties—so Saint Matthew’s “the flesh is weak”—meaning that it dictates its needs with greater force than the nobler spirit. For Augustine, life was “a long, unbroken period of trial” because of our embodied nature, and the immortal soul—the part of being whose job on earth was to hark at divine presence—had to define us more powerfully than biology. God, to whom Augustine speaks in the second person throughout the Confessions, commanded man “to control our bodily desires,” and so “it is by continence that we are made as one and regain that unity of self that we lost by falling apart in the search for a variety of pleasures.” Hence the notion later developed within monastic orders that marriage to Christ is the highest calling, far above marriage to a human whose life is to an extent limited and defined by bodily needs. Augustine confessed to God how his former desires returned to him in his sleep, since they were lodged in his memory. He was mostly able to restrain “the fire of sensuality that provokes me in my sleep,” but not always, and he prayed to God to feel pleasure no longer, even in dreams in which he succumbed to temptation. The body was a site of struggle between a higher calling and the lower appetites of the flesh. Humans, thought Augustine, stood midway between angels and beasts.

Bodily urges, and especially sexual urges, were seen as dangerously misleading and to be feared in their raw state: they are so powerful, triggered as they are by deep biological mechanisms; they take over thoughts and responsibilities; and they do not reflect everything we are, since we are also godly creatures. Urges of the body had to be circumscribed, channeled into codes of behavior and socially sanctioned institutions such as marriage. Women, in whom reason was considered to be weaker than in men, were supposedly even more dominated by passions of the flesh and had to be reined in accordingly; female flesh begets flesh and is menacing to men who try to think their way through and out of flesh.

The Well-Stocked Kitchen, by Joachim Bueckelaer, 1566. Rijksmuseum. In contrast to the abundance of provisions in the foreground, Jesus’ visit to Mary and Martha is depicted inconspicuously in the background.

In fact, the idea of human godliness—and of a divine sphere that sanctions the repression of desire—may have emerged from an awareness of appetites and the need to construct ordered societies to integrate them. In this line of thinking, the right exercise of reason yields right behavior and the control—or even, for the Stoics, the suppression—of appetites and passions. Moral codes in human societies are therefore built on a conception of rationality that stands guard against the riotous passions and ensures their appropriate expression.

From the beginning of thought about the status of flesh, moral knowledge depended on a form of self-knowledge, since it is only by knowing one’s appetites that they can be directed. Plato conceived of the emotions in terms of a tame and a wild horse; both are driven by reason, which is embodied by their charioteer. How appetites are played out is a function of reason and of how well we understand the horses. It is also a kind of medical knowledge, insofar as human behavior depends on degrees of sanity, which is itself dependent on physical health. The ability to balance passions was an index of mental as well as physical health. Balance was central to the Hippocratic humoral scheme that emerged in fifth-century-BC Greece—in parallel with philosophy—and on which medicine and psychology would rely for 2,500 years. According to this scheme, developed in the second century by Galen on the basis of Plato, Aristotle, and the Hellenistic philosophers of the third century BC, we are made of four humors, or fluids, that correspond to elements, their qualities, and their corresponding temperaments. The body was in a constant state of flux, held together, as the third-century theologian (and eventual apostate) Origen wrote, by assimilating “into itself from without certain things for nourishment and, corresponding to the things added, excretes other things.” Health was a state of balance, krasis, between an individual’s humors, themselves formed out of the digestion of food; illness was a state of imbalance, dyskrasia.

Medical and philosophical knowledge were conjoined. The fluids that flowed within flesh—hidden from view by skin, but which occasionally surfaced in various forms (as blood, bile, tears, sweat, saliva, urine, mucus, milk, semen)—affected temperament, mood, and behavior. Ultimately, the humors affected our capacity for wisdom—our ability to act in appropriate ways, on the basis of considered judgment. Aristotle’s ethics posit regulation as the condition for virtue. In his influential scheme, formulated not long after the birth of Hippocratic medicine, emotional extremes were to be avoided. Cowardice and rashness, said Aristotle, should yield to courage in response to fear. To give way to extremes can lead to tragedy—so, for instance, Medea kills her children out of uncontained jealousy.

Given the intricate nature of human sexuality—precisely because, unlike animal sexuality, human sexual relationships take place between complex persons—a doctrine that advocates relinquishing intimacy could seem a relief to tormented souls. There have been ascetics in all religions and cultures, and often the lesser mortals who are tied to embodied callings perceive them as sages. Christianity would not have succeeded had it required of all its followers the abnegation of desire and the repression of ordinary needs.

As the saying goes, an old woman is always uneasy when dry bones are mentioned in a proverb.

—Chinua Achebe, 1958Over centuries, the status of nature itself became a problem. The status of flesh shifted along with views about the relation of nature to the created realm. Where in Greco-Roman paganism all aspects of nature had harbored a divine essence and were associated with a god, for the three Mosaic religions nature was the creation of one god. The question that then arose, and that for centuries would be disputed by Jewish, Christian, and Muslim thinkers—often theologians, philosophers, physicians, and natural philosophers all in one—concerned the limit beyond which nature acts of its own accord, without God’s impetus. The issue of how things moved and transformed was at the forefront of speculation. Magic, which could easily tilt into heresy, never disappeared from the realm of serious investigation into the nature of things. That fluctuating border between nature and God was also the border between flesh and soul. Once it was posited, its position became hard to determine because one realm necessarily determined the other. The most self-evident aspect of our being, our fleshy embodiment, became endlessly confounding. To what extent do humans partake of nature? To what extent is nature a morally acceptable part of humans? To what extent do we differ from beasts?

These questions received complex answers, but they came to a head during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Once the tightly knit classical and scholastic schemes were put in doubt, and Aristotelian physics and biology began to be revised, new considerations of the nature of matter, motion, and flesh—and of the origins of the universe and life on earth—flourished. With these new lines of investigation, one could wonder about what in our embodied behavior was answerable to God, or the authorities that took the place of the transcendent order. It became possible to analyze nature without attention to divinity. Thomas Hobbes described world, man, and mind in entirely materialistic terms. René Descartes set out to replace the Aristotelian system with his own comprehensive picture in which all physical reality, including bodies, would be ultimately accountable in mathematical terms. Mechanisms such as those governing clocks and machines explained the animal organism, of which the human body—set apart from the soul—was one kind. His system still required dualism, the separation of material body and immaterial soul. Cartesian flesh was emptied, however, of its inherent living force, and was turned into a purely mechanical entity. In this scheme, animals have no soul, and hence, no feelings.

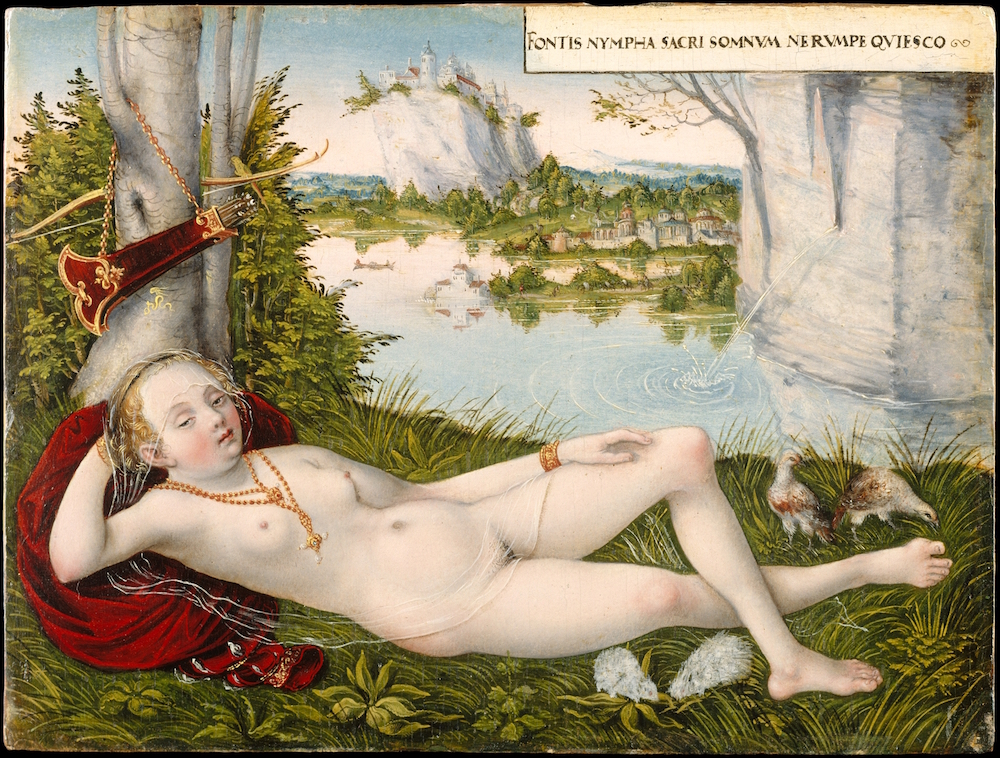

Nymph of the Spring, by Lucas Cranach the Younger, c. 1545–50. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975.

Descartes’ conclusions infuriated many. A powerful alternative to the Cartesian solution came from the priest Pierre Gassendi, who took up the doctrine of atomism from the Roman poet Lucretius, and from the Hellenistic philosopher Epicurus before him. The whole universe consisted of atoms in motion. Gassendi revised this idea to accommodate Christian doctrine, allowing for an initial divine impetus that started the movement of atoms. The cognitive and emotive mind was material too. Gassendism reconciled humanity with animality. No separation was needed between flesh and mental functions, though provision was made for the immortal, rational soul. This corpuscularian hypothesis was adopted in one guise or another by natural philosophers across the English Channel, such as the chemist Robert Boyle, or his acolyte Thomas Willis, the physician who coined the term neurologie and garnered important insights into the brain through his dissections of its flesh. In reaction to these mechanistic philosophies, a vitalist response would grow over the eighteenth century, especially from physicians who claimed that living flesh necessarily harbored a soul, without which it would be dead.

Throughout all these innovations, the physiology beneath the skin did not change. Humoral theory continued to animate it, despite revolutions in anatomy, physics, and chemistry. Emotions, sensations, and perceptions continued to be explained in reference to the fluids, juices, and eventually the nerves that make up sentient organisms. What did change with the new freedom to think outside old strictures was behavior—embodied, intellectual, social. Out of the Gassendist revival of the Lucretian universe, naturalism began to flourish in the seventeenth century. The French libertins were clandestine freethinkers who saw the world in natural, not theological, terms. Mores for them were merely whimsical expressions of social, intellectual, and religious conformity. Behind what had been the fixed ideologies upholding religious and political authority, the libertins saw human nature. Behind high-mindedness, they found embodied passions. Educated women—privileged, usually aristocratic—found freedom through their role as salonnières at houses where a freethinking elite gathered, and where one could debate Cartesianism, politics, religion, and natural philosophy. Ninon de Lenclos hosted one of the great salons of the second half of the seventeenth century. She was Gassendist, a brilliant woman of letters, and a multilingual participant in the debates of the day. She was probably an atheist, and was well known for her many romantic adventures.

With the freedom to look, think, and exert political will at a time of political commotion came new spaces to celebrate the desiring flesh. Writing about sex was in this sense a political act. In eighteenth-century France, from the oppression and pomposity of the ancien régime to the tumultuous days preceding the revolution, there was a profusion of erotic and pornographic literature that was also high-level libertinism. These works were anticlerical and provocative. They told tales where education in the ways of mind and ways of flesh tended to be ironically conjoined. Their main characters were often members of the clergy—priests, monks, nuns—depicted as insatiable lechers, in a titillating mockery of religious hypocrisy that revealed how the care for the soul masked an obsession with the flesh. In 1782, seven years before the fall of the Bastille, Pierre Choderlos de Laclos published Dangerous Liaisons, an epistolary novel so powerful that a half-dozen cinematic adaptations haven’t exhausted its modern pull. Letters offered a voyeuristic reader a glimpse into the minds of characters intent on manipulating the amorous passion of the virtuous Présidente de Tourvel. The conspiring writers, Marquise de Merteuil and the Vicomte de Valmont, act as confused choreographers of a cat-and-mouse game between calculating reason and thoroughly embodied emotions. The passions of the flesh are integral to the epistolary exchange of the novel—and a world apart from Augustine.

The story of how the Renaissance imagination gave way to the scientific revolution and Enlightenment ideals—as well as counterattacks by obscurantist forces—has been told many times. But it is still relevant. Today, more than ever, we view ourselves as part of nature, accountable in terms of biology. We have given up, at least in principle, our exceptional status among earth’s other creatures. Yet we remain puzzled by the relation of flesh to thought. We are ill at ease before death, even as we are confused about how free we are to manipulate the natural order science reveals, even as we are able to replace organs or create a new face, to procreate without sex, and to change sex. We understand our biology more precisely, but human behavior is as violent as ever toward nature, animals, and one another. The technology of killing is the curse of Homo sapiens. Humans lash out against other humans, intent on flaying, torturing, and relishing in the horror of maimed flesh. We are glad, it seems, of flesh’s fragility. We revel in the blood that flows so easily once skin is pierced, and in the power conferred by our ability to turn persons into meat. The infernal dance of Thanatos squeezing life out of Eros has never stopped.

It hurts to watch the fluency of a body acclimated to its shackling.

—Leslie Jamison, 2014The drives that push us to desire and also to destroy arise from operations that are not immediately available to the higher mind described by religion. Most of the time we are not aware of our viscera. We are the sum of our parts and of the many complex operations of the nervous and endocrine systems, now understandable from the molecular and cellular levels on up. We can see the stuff we are made of from outside ourselves. But we cannot reconcile what we see with what we feel ourselves to be. Nor are we very good at paying attention to our gut feelings. We see ourselves as one form, skin uniformly constituting us, fleshing out our vanity, wrinkles aging us from the outside. We think of muscles and fat as supports for skin and the factors of external beauty, rather than skin as the protector of everything within. Our organs manifest themselves at various times of the day and night, but we think of them as separate from ourselves—until one of them breaks down.

It is perhaps because we are so good at ignoring our bodily sensations that there is such a strong cultural pull to imagine we can transcend flesh and create smooth, ageless robots. Yet we know today that life is inherent in flesh. It is evolved, passed on through the genes that Gregor Mendel discovered in the nineteenth century. Whatever it is that is called soul does not hover over our messily, miraculously embodied being. We still hanker for it, no doubt. We don’t always want to be mere flesh and blood, not when there is pain, illness, and death lurking just on the other side of pleasure, sensuality, and birth. We live squeezed between these bookends, flesh manifest.