I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who has endowed us with sense, reason, and intellect has intended us to forgo their use.

—Galileo Galilei, 1615

The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man, by Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder, c. 1615. Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

Hardly anyone noticed this summer when former president Jimmy Carter explained why he had decided to leave the Baptist Church. However “painful and difficult,” wrote Carter in an essay that appeared in the Guardian, his break with the denomination to which he had belonged for sixty years had begun to seem like the only possible response to past opinions expressed and codified by the Southern Baptist Convention. “It was an unavoidable decision when the convention’s leaders, quoting a few carefully selected Bible verses and claiming that Eve was created second to Adam and responsible for original sin, ordained that women must be ‘subservient’ to their husbands and prohibited from serving as deacons, pastors, or chaplains in the military service. This was in conflict with my belief—confirmed in the holy scriptures—that we are all equal in the eyes of God.”

Considerably more attention was generated some months earlier by another story about how religion conceives and enforces its view of a woman’s place. The horrific attack on two Afghan girls en route to school—the young women were severely disfigured by acid allegedly thrown by Taliban fighters—was widely reported and discussed. Obviously, the assault was more brutal, shocking, and newsworthy than an elderly white guy’s regretful decision to separate himself from the misguided pronouncements of some other elderly white guys. And just as clearly, the Taliban’s plans for women far exceed the darkest imaginings of the Southern Baptists, whose tenets—“a wife is to submit herself graciously to the servant leadership of her husband”—seem genial and reassuringly vague when compared to the restrictions that the Taliban impose, and seek to impose, on women, regulations that narrow the parameters of daily life down to a space in which anyone, male or female, would suffocate. Under Taliban rule Afghan women cannot work, attend school, leave home without a male chaperone, or ride in a taxi. Minor infractions, such as showing an ankle, are punished by public whippings. More serious violations, such as adultery, are capital crimes for which the sentence is death by hanging or stoning.

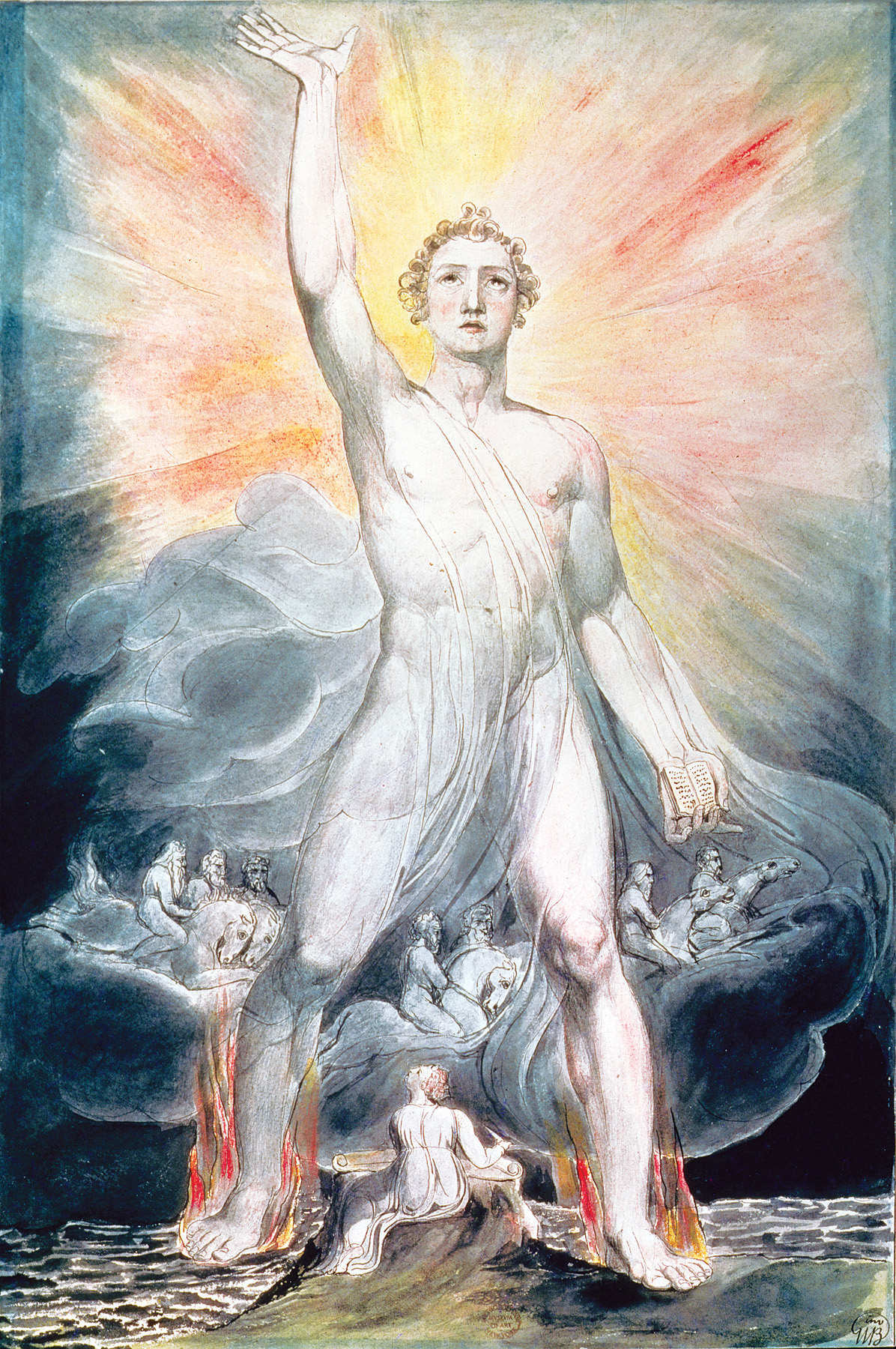

Angel of the Revelation, by William Blake, c. 1803–05. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1914.

The acid attack on the schoolgirls offered graphic and persuasive confirmation of one reason why we have gone to war, or in any case one reason we’ve been given: according to some, once we defeat the Taliban, every Afghan girl can go to school. That’s the outcome everyone wants, though it is less often mentioned that literacy rates among Afghan women were appallingly low long before the Taliban, back in the 1980s when we were still arming the mujahideen—including many future Taliban warriors—to fight against the Russians. The Taliban’s demonic and demonizing attitude toward women represents merely the most current extreme manifestation of the grotesque misogyny fostered throughout history by religion and patriarchal tribal culture. Both the Taliban and the Southern Baptists employ the “lessons” of biology and scripture to “prove” women’s inferiority, a view of our gender unlikely to be eliminated by another air strike or drone-missile deployment, or by the polite demurrals of a former president.

Sensible, decent Jimmy Carter got it right again. “This view that women are somehow inferior to men is not restricted to one religion or belief. It is widespread. Women are prevented from playing a full and equal role in many faiths. Nor, tragically, does its influence stop at the walls of the church, mosque, synagogue, or temple. This discrimination, unjustifiably attributed to a higher authority, has provided a reason or excuse for the deprivation of women’s equal rights across the world for centuries. The male interpretations of religious texts and the way they interact with and reinforce traditional practices justify some of the most pervasive, persistent, flagrant, and damaging examples of human-rights abuses.”

Like countless theologians, clerics, and believers, Carter distinguishes between the ideas expressed by the founders of those faiths and the distortions and biases of those who organized and spread the religion. But how much comfort, finally, can women take in knowing that it wasn’t God, Jesus, or the Prophet but some later rabbi, Church Father, or caliph who banned them from praying during their menstrual periods, who forbid them to enter a mosque or feel the sun on their faces, who ruled that their husbands could beat them for disobedience, and who first suggested that each and every one of them was a living reminder of the permanent harm that Eve had done humankind?

Almost as soon as anyone (mostly women, for obvious reasons) started noticing or asking how the world’s religions viewed their female adherents, women—and I would assume some men—either had to face it or not, make excuses or not, question their faith or not. During the 1970s, feminists called attention to any number of ancient fertility-mother cults. But though pre-Christian cultures had goddesses, and priestesses in their temples, Greek and Roman myths are essentially crime blotters recording rapes, near rapes, and metamorphoses into animals or plants to avoid or atone for being raped. There is no word for heroine in Homeric Greek.

Judaism did little to challenge men’s most primitive suspicions of and prejudices against women. The Old Testament abounds with stories of women sold and traded like cattle, of marriageable girls held hostage in return for years of hard labor by their suitors. Of course there are also stories of women who defy male authority, such as Queen Esther, who dared approach the king without being asked, and Deborah, who accompanied the Israelites into battle. But according to Leviticus, only sons may partake of the meat of the sacred burnt offering, and after childbirth, women must arrange for sacrifice—a lamb or, in the absence of a lamb, two turtle doves or young pigeons—to end their term of “uncleanness,” a week if they’ve given birth to a son, two weeks if it’s a girl. Each month, after her period, a woman must undergo a strenuous head-to-toe purification. Measures are taken, as in Islam, to protect men from temptation. Some observant Jewish wives must shave their heads, lest the sight of a ringlet cause a man to lose all self-control. Many Jewish men begin their day with a prayer thanking God for not having been born female. For the last decades of her life, my mother, a scientist and a doctor, attended High Holy Day services at a Greenwich Village synagogue with a separate women’s section up in the balcony, farther from the action—presumably so that her white hair and frail shoulders would not distract a man from the serious business of prayer.

However radical the changes that Jesus and his disciples made to Old Testament theology, they did little to modify or improve the patriarchs’ most neurotic anxieties and destructive biases against women. Uta Ranke-Heinemann’s scholarly and wry Eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven catalogues the jaw-dropping and (if one can maintain a sense of humor about sexual hatred and vilification) hilarious insults that the Church Fathers, among them St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, routinely leveled at women. In one unsettling chapter, Ranke-Heinemann—a Catholic theologian and the first woman to hold a distinguished chair in theology at the University of Essen, from which she was fired in 1987 for suggesting that the Virgin Birth was a matter of faith and not a biological fact—discusses the prohibitions that have resulted from the Church’s solemn responsibility to keep inferior beings from assuming the privileges or rightful duties of their betters.

According to the Apostolic Constitutions, a fourth-century compilation from older writings on church liturgy and canon law, if Jesus wanted women to hold ecclesiastical office, he would have found and appointed a woman disciple; after all, there were plenty of women around. And if the man was the head of the household, the existence of a female priest in the house would mean that the body was ruling the head—and how unnatural would that be? “In keeping with the will of their spiritual lords, women in church had to be quiet, so quiet that they could only move their lips without making a sound.”

Witches’ Sabbath (Aquelarre), by Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, c. 1820–23. Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain.

Long before Muhammad, St. Ambrose forbade women to teach in church and John Chrysostom suggested that women be veiled in public. One early Christian philosopher after another (quite a few of them saints, such as St. Jerome) emphasized the fact that woman’s only purpose on earth, indeed her only route to salvation, was to provide her husband with children. For anything else that was necessary, for work or companionship, advice or entertainment, he would sensibly and naturally choose another man. In St. Augustine’s essay “On Marriage and Concupiscence,” the author of Confessions sounds remarkably like the Southern Baptist Convention. “Nor can it be doubted that it is more consonant with the order of nature that men should bear rule over women, than women over men. It is with this principle in view that the apostle says, ‘The head of the woman is the man,’ and ‘Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands.’”

The Church Fathers devoted considerable energy to debating the question of whether sex with a beautiful woman was more or less sinful than sex with an ugly one, as well as the subject of whether or not Adam and Eve had intercourse in Paradise before the fall of man. By contrast, there was little disagreement about whose fault that was. Whom would the serpent choose to tempt—the man who had named the animals or his foolish wife? Poor Eve: one bite of fruit, and centuries of blame for every small or severe pain that measures our distance from Eden.

Ranke-Heinemann tracks much of this back to the body-hating, pleasure-despising strain introduced into the early church by the Essenes and Gnostics. Later, the early and medieval saints and theologians would show little interest in concealing their horror of sex and the body. According to one thought often attributed to Thomas Aquinas, any variation on the so-called missionary position was as sinful as having intercourse with one’s own mother.

The debate over sex with the beautiful versus sex with the ugly had its twisted roots in the belief that there was an almost mathematical ratio between pleasure and sin. The greater the pleasure, the worse the evil. Apparently, too, there also was considerable worry about ejaculation as something that drains and weakens the male, a dangerous process in general and particularly in the presence of the predatory woman who, unlike her mate, doesn’t lose in sex a life-sustaining fluid. The rabbinic admonition to think of a woman as “a pitcher of filth with its mouth full of blood” was echoed in the work of the twelfth-century theologian Petrus Cantor. “Consider that the most lovely woman has come into being from a foul-smelling drop of semen; then consider her midpoint, how she is a container of filth; and after that consider her end, when she will be food for worms.”

We have just enough religion to make us hate, but not enough to make us love one another.

—Jonathan Swift, 1706To ask which came first—fear of women or fear of sex—is one of those chicken-and-egg questions more suited to Zen meditation than logical inquiry. In any case, religion is an aid to those who suffer from either, or both, terrors. Orthodox Judaism assumes the disgustingness of female bodily fluids, especially those that accompany every child’s entrance into the world. Christianity saw no reason to challenge the Old Testament ban on sex with menstruating women, a prohibition which also appears in the Qur’an. But it’s more than a physical thing. What’s at issue here is not merely a horror of the other but an awareness of the way that horror can augment one’s sense of self, an acknowledgement of how the conviction of God-granted superiority can be a source of comfort and self-esteem. What man wouldn’t have more confidence moving through the world with a submissive wife or wives shuffling like ducklings behind him? Conversely, any indication that the woman is catching up to walk alongside or, worse yet, ahead, inspires even in decent men a frenzy of maddened, injurious activity, as if one’s own masculinity and the fragile social structure that masculinity has created will survive or shatter depending on whether or not a man continues to win that race. Such fears must feed the perpetual worry that one is sharing his bed with an enemy, an inferior, a repellent but necessary specimen of an alien species. And how useful religion is in helping us sort all that out! Every modern society—from Puritan New England to France under Napoleon, from Nazi Germany to Eisenhower-era America—has understood the importance, the necessity, of keeping women in their place.

To automatically hate and fear anything or anyone different from ourselves and to want to feel smarter and worthier than an entire race or gender are two of the least admirable and most regrettable aspects of human nature. So it does seem peculiar that religion, with its emphasis on self-perfection through prayer and the help of God, should so rarely include intolerance among the roster of sins for which we wish to be forgiven, or to avoid altogether. Strange, but not so very strange, when we consider that religions are not merely belief systems but social institutions whose leaders have always understood how effectively fear, hate, and the assurance of racial, national, or sexual superiority—and sex—can be used to define and control a society.

Ages before Freud, it was understood that the power of sex was a potential agent of destabilization and chaos. Consider the story of Paris and Helen of Troy, or Tristan and Isolde. Unruly erotic attraction is a major reason why people break rules, sometimes with tragic results. The theologians were right about one thing: follow your desires, and things start to fall apart. How much simpler it is to tell a community of celibate monks when to go to sleep and get up, and what to do every minute in between, than it is to rein in a teenage boy who wants to go visit his girlfriend. Some politicians have long understood that regimenting sexuality is a time-tested way of maintaining moral authority. And the fear of women and of everything that women represent—the fear of life, of sex, of fecundity, of birth and rebirth and renewal—fosters the kind of death worship that in turn fosters more wars, more killing, more repression, and more pointless misery.

Like every means of social control, faith-based misogyny has its cost, and women have been made to pay an unequal fraction of the price. Let me quote Jimmy Carter one last time, for the exactitude with which he connects the dots between the ideology of the Southern Baptist Convention and the mistreatment of women worldwide. “At its most repugnant, the belief that women must be subjugated to the wishes of men excuses slavery, violence, forced prostitution, genital mutilation, and national laws that omit rape as a crime. But it also costs millions of girls and women control over their own bodies and lives, and continues to deny them fair access to education, health, employment, and influence within their own communities.”

Lately, there have been some signs of progress, shifts perhaps more visible to the optimist than to the impatient. One sees chadors being shed by female protestors in the streets of Tehran; lending cooperatives and trade schools have been established to help Muslim women hold jobs outside the family compound. Women appear more often in Protestant and Jewish pulpits. There’s no doubt that many women’s lives are better than they were a century, even a half century, ago. Women can vote and own property. Abortion has been legalized in many countries, at least for the moment. But organized religion, and the anxieties and terrors it encourages and employs as a means of social control, have fought—and continue to fight—these positive changes, every step of the way. Despite the small steps forward, life continues to worsen for, among others, Afghan women, whose rights were limited this year by the Shiite Personal Status Law, which restricts women’s rights to inherit or divorce and legalizes marriage to minors. Daily, all over the world, there are mutilations and murders and beatings, all in the name of God. Women and men everywhere are still being made to suffer in a continual retelling of that old Bible story of headstrong, impossible Eve, who was the first person to step out of line and question what she had been told.