December 1944

Starvation is everywhere; each of us is nothing more than a shadow. The food we receive gets scarcer each day. For three days we haven’t seen a piece of bread. Some people have saved theirs and now they open up their miserable provisions and everything is moldy. Bread is gold. You can get anything with bread; you will risk everything for bread. And there are more and more thieves, especially at night. Someone suggested we take turns staying up and keeping watch so we could catch them. The hunt lasted two nights in the densest darkness. It was very dramatic, very noisy. No one slept, and the results were nil.

Anyone who has a little bit of bread keeps it under his pillow or rather makes a pillow out of it. That way they feel more secure when they sleep. The mothers, especially, resort to this method to ensure a few mouthfuls for their children. As for the workers who are out working all day, they’re forced to lug their entire stock with them everywhere in their bag. And their entire stock means six days’ rations, at most, which is about half a loaf. The temptation is strong. Everyone ends up at some point eating the entire six days’ worth in one day.

Yesterday, on the way to work (in the women’s commando), we saw potatoes on the road; they had probably fallen from a truck or been thrown out by people from the last transport during a too long and painful march, when you prefer to run the risk of dying of hunger so as not to die of fatigue. We know all about this. And so, with our famished eyes, we caught sight of a few potatoes. One of us bent down to pick one up. But she had to drop it immediately, frightened by the savage screams of the soldier accompanying us who couldn’t tolerate so much gluttony.

January 1945

No baths, no hot water. These are only dreams now. The only thing left for us is to take advantage of the camp’s wash houses, infectious, frozen. We undress en masse, all together, cramped, jostled. No point in waiting “your turn,” because there are too many of us and the spigots are always taken—unless, of course, the water is turned off. We undress hastily in the bitter cold, all of us, men, women pell-mell. Nobody is embarrassed. No one pays any attention to the person washing himself next to him. Besides, sex has no meaning here. The important thing is to scrub yourself. Teeth chatter, the icy water burns the skin; it’s painful, but it doesn’t matter.

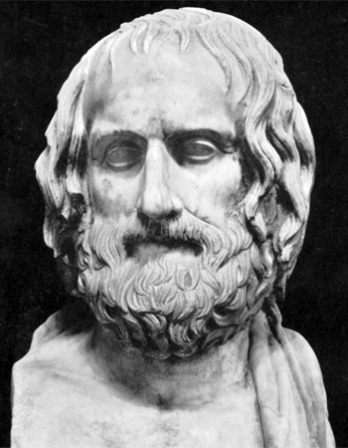

Fasting Siddhartha, Pakistan, c. third century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As for the constant hunger, our bodies have grown accustomed to it. It happens that someone who is tortured by the acute pain of hunger, who can’t stand it anymore, ends up eating his entire reserve bread (three or four rations) all at once, or exchanging his clothes for one or two bowls of soup (offered by thieves)…And when he has swallowed this unusual quantity of wretched food, he feels ill, worse than before, his body protests violently. He’s left with nausea, and his hunger remains unappeased.

We receive our food more and more irregularly. The noontime soup gets distributed at five or six o’clock in the evening, and the evening meal (boiled water or a little piece of synthetic cheese) has been crossed off the agenda until the following morning…or not at all. That’s why we sometimes go sixteen to twenty hours with nothing. And naturally, at the first distribution after such a long wait, famished bodies throw themselves on the vats; the sad consequences are inevitable a few hours later: collective diarrhea infests the whole area.

January 1945

Starvation is everywhere. We only manage to move with great difficulty. No one can walk straight anymore. Everyone staggers or drags their feet. Entire families die in a matter of days. The elderly Mrs. M died quickly; two days later her husband died. Then came their children’s deaths, devoured by famine and fleas. One of them, a nearsighted young boy, couldn’t kill the vermin that had settled on his body because he couldn’t see them; they’ve burrowed deep into his skin and swarmed through his eyebrows. His chest is completely blackened by these thousands of fleas and their nests.

February 1945

Everyone thinks only of himself. No one feels anything for anyone else. Many women have given in. Young girls who’ve known nothing of life or its foundations have heedlessly seized what these pitiful circumstances offer them and have yielded. Carousing, flirting, drinking, dancing, singing, laughing out loud, wearing silk stockings and beautiful dresses—this is their lifestyle here, in league with the Kapos.

Hunger crushes the spirit. I feel my physical and intellectual strength diminishing. Things escape me, I can’t think properly, can’t grasp events, can’t realize the full horror of the situation. Only once in a while, in moments as brief as a flash of lightning, a clear and precise thought crosses my mind and I wonder: what is this dark, perverse, underhanded force that succeeds in hurling humanity as a whole into such absurd and abominable conditions?

©2009 by Amira Hass. Used with permission of Haymarket Books.

From Diary of Bergen-Belsen. Born into a Jewish family in Sarajevo in 1913, Lévy-Hass studied in Belgrade in the 1930s. In 1944 she was captured by German occupation forces and spent a half year in a Gestapo jail before being taken to Bergen-Belsen, a concentration camp in Germany, where mass deaths resulted from starvation and disease. Her diary was first published in English in 1982. She died in Jerusalem at the age of eighty-eight.

Back to Issue