Having already made my protestations not only against the illegality of this pretended court but also that no earthly power can justly call me (who am your king) in question as a delinquent, I would not any more open my mouth upon this occasion more than to refer myself to what I have spoken, were I in this case alone concerned, but the duty I owe to God in the preservation of the true liberty of my people will not suffer me at this time to be silent. For how can any freeborn subject of England call life or anything he possesses his own if power without right daily makes new and abrogates the old fundamental ways of the land, which I now take to be the present case?

And admitting, but not granting, that the people of England’s commission could grant your pretended power, I see nothing you can show for that; for certainly you never asked the question of the tenth man in the kingdom, and in this way you manifestly wrong even the poorest plowman if you demand not his free consent; nor can you pretend any color for this, your pretended commission, without the consent at least of the major part of every man in England of whatsoever quality or condition, which I am sure you never went about to seek, so far are you from having it. Thus you see that I speak not for my own right alone, as I am your king, but also for the true liberty of all my subjects, which consists not in the power of government but in living under such laws, such a government, as may give themselves the best assurance of their lives and property of their goods. Nor in this must or do I forget the privileges of both houses of Parliament, which this day’s proceedings do not only violate but likewise occasion the greatest breach of their public faith that (I believe) ever was heard of—with which I am far from charging the two houses: for all the pretended crimes laid against me bear dates long before this treaty at Newport, in which I, having concluded as much as in me lay, and hopefully expecting the houses’ agreement thereunto, I was suddenly surprised and hurried from thence as a prisoner, upon which account I am against my will brought hither, where since I am come, I cannot but, to my power, defend the ancient laws and liberties of this kingdom, together with my own just right. Then, for anything I can see, the higher house is totally excluded. And for the House of Commons, it is too well known that the major part of them are detained or deterred from sitting; so as, if I had no other, this were sufficient for me to protest against the lawfulness of your pretended court. Besides all this, the peace of the kingdom is not the least in my thoughts; and what hopes of settlement is there, so long as power reigns without rule or law, changing the whole frame of that government, under which this kingdom hath flourished for many hundred years? (Nor will I say what will fall out, in case this lawless, unjust proceeding against me does go on.) And believe it, the commons of England will not thank you for this change; for they will remember how happy they have been of late years under the reigns of Queen Elizabeth, the king my father, and myself, until the beginning of these unhappy troubles, and will have cause to doubt that they shall never be so happy under any new. And by this time it will be too sensibly evident that the arms I took up were only to defend the fundamental laws of this kingdom against those who have supposed my power hath totally changed the ancient government.

Thus having showed you briefly the reasons why I cannot submit to your pretended authority without violating the trust which I have from God for the welfare and liberty of my people, I expect from you either clear reasons to convince my judgment, showing me that I am in an error—and then truly I will answer—or that you will withdraw your proceedings.

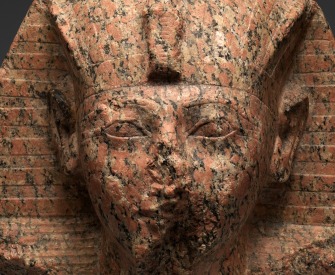

From “The King’s Reasons for Declining the Jurisdiction of the High Court of Justice.” A believer in the divine right of kings, Charles often clashed with the House of Commons. In early 1647 parliamentary forces placed him under house arrest, which he attempted to evade through secret negotiations with Scotland. After England defeated Scotland at the Battle of Preston, Charles was put on trial as “the grand author of our troubles.” He was beheaded in January 1649, declaring before his execution that “for the people…I desire their liberty and freedom as much as anybody,” but “their liberty and freedom consists in having government.”

Back to Issue