Many are the wonders of the world, and none so wonderful as man.

—Sophocles, 441 BCAlchemy By Other Means

“The evils of paper money have no end.”

I remember a German farmer expressing as much in a few words as the whole subject of paper money requires: “Money is money, and paper is paper.” All the invention of man cannot make them otherwise. The alchemist may cease his labors, and the hunter after the philosopher’s stone go to rest, if paper can be metamorphosed into gold and silver, or made to answer the same purpose in all cases.

Gold and silver are the emissions of nature: paper is the emission of art. The value of gold and silver is ascertained by the quantity which nature has made in the earth. We cannot make that quantity more or less than it is, and therefore the value being dependent upon the quantity, depends not on man. Man has no share in making gold or silver; all that his labors and ingenuity can accomplish is to collect it from the mine, refine it for use, and give it an impression, or stamp it into coin.

Its being stamped into coin adds considerably to its convenience but nothing to its value. It has then no more value than it had before. Its value is not in the impression but in itself. Take away the impression and still the same value remains. Alter it as you will, or expose it to any misfortune that can happen, still the value is not diminished. It has a capacity to resist the accidents that destroy other things. It has, therefore, all the requisite qualities that money can have and is a fit material to make money of, and nothing which has not all those properties can be fit for the purpose of money.

Paper, considered as a material whereof to make money, has none of the requisite qualities in it. It is too plentiful, and too easily come at. It can be had anywhere, and for a trifle.

There are two ways in which I shall consider paper.

Self Portrait as Dirty Princess, by Julie Heffernan, 2004. Oil on canvas, 75" x 68". © Julie Heffernan, courtesy of the artist and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York.

The only proper use for paper in the room of money is to write promissory notes and obligations of payment in specie upon. A piece of paper, thus written and signed, is worth the sum it is given for, if the person who gives it is able to pay it, because in this case the law will oblige him. But if he is worth nothing, the paper note is worth nothing. The value, therefore, of such a note is not in the note itself, for that is but paper and promise, but in the man who is obliged to redeem it with gold or silver.

Paper, circulating in this manner, and for this purpose, continually points to the place and person where, and of whom, the money is to be had, and at last finds its home; and, as it were, unlocks its master’s chest and pays the bearer.

But when an assembly undertakes to issue paper as money, the whole system of safety and certainty is overturned, and property set afloat. Paper notes given and taken between individuals as a promise of payment is one thing, but paper issued by an assembly as money is another thing. It is like putting an apparition in the place of a man; it vanishes with looking at, and nothing remains but the air.

Money, when considered as the fruit of many years’ industry, as the reward of labor, sweat, and toil, as the widow’s dowry and children’s portion, and as the means of procuring the necessaries and alleviating the afflictions of life, and making old age a scene of rest, has something in it sacred that is not to be sported with, or trusted to the airy bubble of paper currency.

By what power or authority an assembly undertakes to make paper money is difficult to say. It derives none from the constitution, for that is silent on the subject. It is one of those things which the people have not delegated, and which, were they at any time assembled together, they would not delegate. It is, therefore, an assumption of power which an assembly is not warranted in, and which may one day or other be the means of bringing some of them to punishment.

One of the evils of paper money is that it turns the whole country into stockjobbers. The precariousness of its value and the uncertainty of its fate continually operate night and day to produce this destructive effect. Having no real value in itself, it depends for support upon accident, caprice, and party, and as it is the interest of some to depreciate and of others to raise its value, there is a continual invention going on that destroys the morals of the country.

It was horrid to see, and hurtful to recollect, how loose the principles of justice were let, by means of the paper emissions during the war. The experience then had should be a warning to any assembly how they venture to open such a dangerous door again.

As to the romantic, if not hypocritical, tale that a virtuous people need no gold and silver and that paper will do as well, requires no other contradiction than the experience we have seen. Though some well-meaning people may be inclined to view it in this light, it is certain that the sharper always talks this language.

There are a set of men who go about making purchases upon credit and buying estates they have not wherewithal to pay for, and having done this, their next step is to fill the newspapers with paragraphs of the scarcity of money and the necessity of a paper emission, then to have a legal tender under the pretence of supporting its credit—and when out, to depreciate it as fast as they can, get a deal of it for a little price, and cheat their creditors; and this is the concise history of paper-money schemes.

But why, since the universal custom of the world has established money as the most convenient medium of traffic and commerce, should paper be set up in preference to gold and silver? The productions of nature are surely as innocent as those of art, and in the case of money, are abundantly, if not infinitely, more so. The love of gold and silver may produce covetousness, but covetousness, when not connected with dishonesty, is not properly a vice. It is frugality run to an extreme.

But the evils of paper money have no end. Its uncertain and fluctuating value is continually awakening or creating new schemes of deceit. Every principle of justice is put to the rack, and the bond of society dissolved: the suppression, therefore, of paper money might very properly have been put into the act for preventing vice and immorality.

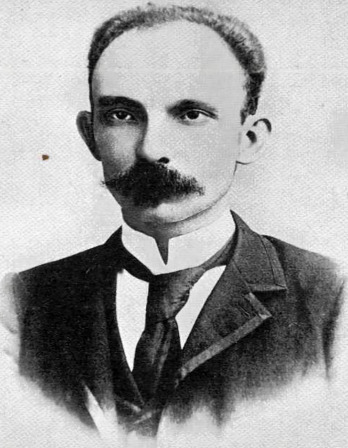

Thomas Paine

From “Dissertation on Paper Money.” Born in 1737 to a Quaker father and an Anglican mother in England, Paine in 1774 met Benjamin Franklin, who convinced the twice-married and recently dismissed officer of the excise to move to America. Nine months after the Battle of Concord and Lexington, Paine published Common Sense, selling 500,000 copies within a matter of months. He published his defense of the French Revolution, Rights of Man, in two parts between 1791 and 1792.