Memory is a complicated thing, a relative to truth but not its twin.

—Barbara Kingsolver, 1990The Past Also Rises

George Eliot finds a character lost in regret.

Bulstrode felt himself helpless. It was not that he was in danger of legal punishment or of beggary; he was in danger only of seeing disclosed to the judgment of his neighbors and the mournful perception of his wife certain facts of his past life which would render him an object of scorn and an opprobrium of the religion with which he had diligently associated himself.

The terror of being judged sharpens the memory: it sends an inevitable glare over that long-unvisited past which has been habitually recalled only in general phrases. Even without memory, the life is bound into one by a zone of dependence in growth and decay; but intense memory forces a man to own his blameworthy past. With memory set smarting like a reopened wound, a man’s past is not simply a dead history, an outworn preparation of the present; it is not a repented error shaken loose from the life; it is a still-quivering part of himself, bringing shudders and bitter flavors and the tinglings of a merited shame.

Into this second life Bulstrode’s past had now risen, only the pleasures of it seeming to have lost their quality. Night and day, without interruption save of brief sleep which only wove retrospect and fear into a fantastic present, he felt the scenes of his earlier life coming between him and everything else, as obstinately as when we look through the window from a lit room, the objects we turn our backs on are still before us, instead of the grass and the trees. The successive events inward and outward were there in one view; though each might be dwelled on in turn, the rest still kept their hold in the consciousness.

Once more he saw himself the young banker’s clerk, with an agreeable person, as clever in figures as he was fluent in speech and fond of theological definition: an eminent though young member of a Calvinistic dissenting church at Highbury, having had striking experience in conviction of sin and sense of pardon. Again he heard himself called for as Brother Bulstrode in prayer meetings, speaking on religious platforms, preaching in private houses. Again he felt himself thinking of the ministry as possibly his vocation, and inclined toward missionary labor. That was the happiest time of his life; that was the spot he would have chosen now to awake in and find the rest a dream. The people among whom Brother Bulstrode was distinguished were very few, but they were very near to him and stirred his satisfaction the more; his power stretched through a narrow space, but he felt its effect the more intensely. He believed without effort in the peculiar work of grace within him and in the signs that God intended him for special instrumentality.

Then came the moment of transition; it was with the sense of promotion he had when he, an orphan educated at a commercial charity school, was invited to a fine villa belonging to Mr. Dunkirk, the richest man in the congregation. Soon he became an intimate there, honored for his piety by the wife, marked out for his ability by the husband, whose wealth was due to a flourishing City and West End trade. That was the setting in of a new current for his ambition, directing his prospects of “instrumentality” toward the uniting of distinguished religious gifts with successful business.

By and by came a decided external leading: a confidential subordinate partner died, and nobody seemed to the principal so well fitted to fill the severely felt vacancy as his young friend Bulstrode, if he would become confidential accountant. The offer was accepted. The business was a pawnbroker’s, of the most magnificent sort both in extent and profits; and on a short acquaintance with it, Bulstrode became aware that one source of magnificent profit was the easy reception of any goods offered, without strict inquiry as to where they came from. But there was a branch house at the West End, and no pettiness or dinginess to give suggestions of shame.

He remembered his first moments of shrinking. They were private and were filled with arguments, some of these taking the form of prayer. The business was established and had old roots; is it not one thing to set up a new gin palace and another to accept an investment in an old one? The profits made out of lost souls—where can the line be drawn at which they begin in human transactions? Was it not even God’s way of saving his chosen? “Thou knowest”—the young Bulstrode had said then, as the older Bulstrode was saying now—“Thou knowest how loose my soul sits from these things, how I view them all as implements for tilling thy garden rescued here and there from the wilderness.”

Metaphors and precedents were not wanting; peculiar spiritual experiences were not wanting which at last made the retention of his position seem a service demanded of him: the vista of a fortune had already opened itself, and Bulstrode’s shrinking remained private. Mr. Dunkirk had never expected that there would be any shrinking at all; he had never conceived that trade had anything to do with the scheme of salvation. And it was true that Bulstrode found himself carrying on two distinct lives; his religious activity could not be incompatible with his business as soon as he had argued himself into not feeling it incompatible.

Mentally surrounded with that past again, Bulstrode had the same pleas—indeed, the years had been perpetually spinning them into intricate thickness, like masses of spiderweb, padding the moral sensibility; nay, as age made egoism more eager but less enjoying, his soul had become more saturated with the belief that he did everything for God’s sake, being indifferent to it for his own. And yet—if he could be back in that far-off spot with his youthful poverty—why, then he would choose to be a missionary.

But the train of causes in which he had locked himself went on. There was trouble in the fine villa at Highbury. Years before, the only daughter had run away, defied her parents, and gone on the stage; and now the only boy died, and after a short time Mr. Dunkirk died also. The wife, a simple, pious woman, left with all the wealth in and out of the magnificent trade, of which she never knew the precise nature, had come to believe in Bulstrode and innocently adore him as women often adore their priest or “man-made” minister. It was natural that after a time marriage should have been thought of between them. But Mrs. Dunkirk had qualms and yearnings about her daughter, who had long been regarded as lost both to God and her parents. It was known that the daughter had married, but she was utterly gone out of sight. The mother, having lost her boy, imagined a grandson and wished in a double sense to reclaim her daughter. If she were found, there would be a channel for property, perhaps a wide one, in the provision for several grandchildren. Efforts to find her must be made before Mrs. Dunkirk would marry again. Bulstrode concurred; but after advertisement as well as other modes of inquiry had been tried, the mother believed that her daughter was not to be found and consented to marry without reservation of property.

The daughter had been found, but only one man besides Bulstrode knew it, and he was paid for keeping silence and carrying himself away.

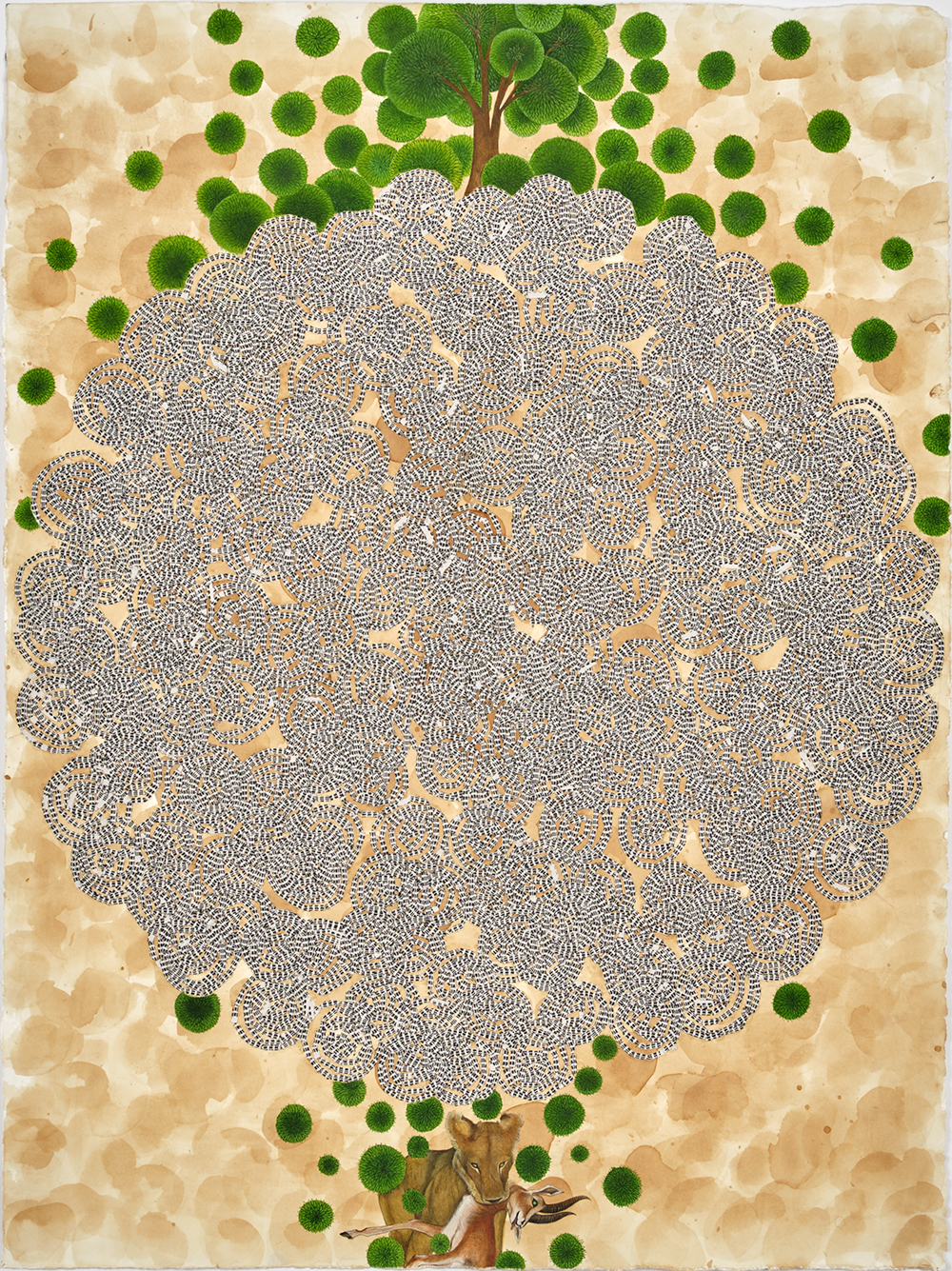

Asadullah (9), by Ambreen Butt, 2019. Watercolor and collage of text on tea-stained paper, 29 x 21 inches. © Ambreen Butt, courtesy the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

That was the bare fact which Bulstrode was now forced to see in the rigid outline with which acts present themselves to onlookers. But for himself at that distant time, and even now in burning memory, the fact was broken into little sequences, each justified as it came by reasonings which seemed to prove it righteous. Bulstrode’s course up to that time had, he thought, been sanctioned by remarkable providences, appearing to point the way for him to be the agent in making the best use of a large property and withdrawing it from perversion. Death and other striking dispositions, such as feminine trustfulness, had come; and Bulstrode would have adopted Cromwell’s words—“Do you call these bare events? The Lord pity you!” The events were comparatively small, but the essential condition was there, namely, that they were in favor of his own ends. It was easy for him to settle what was due from him to others by inquiring what were God’s intentions with regard to himself. Could it be for God’s service that this fortune should in any considerable proportion go to a young woman and her husband who were given up to the lightest pursuits and might scatter it abroad in triviality—people who seemed to lie outside the path of remarkable providences? Bulstrode had never said to himself beforehand, “The daughter shall not be found”; nevertheless, when the moment came he kept her existence hidden, and when other moments followed, he soothed the mother with consolation in the probability that the unhappy young woman might be no more.

There were hours in which Bulstrode felt that his action was unrighteous, but how could he go back? He had mental exercises, called himself naught, laid hold on redemption, and went on in his course of instrumentality. And after five years Death again came to widen his path by taking away his wife. He did gradually withdraw his capital, but he did not make the sacrifices requisite to put an end to the business, which was carried on for thirteen years afterward before it finally collapsed. Meanwhile, Nicholas Bulstrode had used his hundred thousand discreetly and was become provincially, solidly important—a banker, a churchman, a public benefactor; also a sleeping partner in trading concerns, in which his ability was directed to economy in the raw material. And now when this respectability had lasted undisturbed for nearly thirty years—when all that preceded it had long lain benumbed in the consciousness—that past had risen and immersed his thought as if with the terrible eruption of a new sense overburdening the feeble being.

George Eliot

From Middlemarch. Under this pseudonym, the novelist and critic Mary Ann Evans published this, her sixth novel, in eight parts in 1871–72. The work was a critical and commercial success, selling nearly twenty thousand copies by the end of 1874 and drawing praise from Sigmund Freud and Edith Simcox. When Eliot’s husband, the banker John Walter Cross, wrote a biography of his late wife, he chose as the book’s epigraph a line of verse from the epilogue to her novel Felix Holt, the Radical, believing it a succinct summation of her body of work: “Our finest hope is finest memory.”