God gave to mankind in general dominion over all the creatures of the earth, from the first creation of the world, a grant which was renewed upon the restoration of the world after the deluge.

All things formed a common stock for all mankind, as inheritors of one general patrimony. From hence it happened that every man seized to his own use or consumption whatever he met with, a general exercise of a right, which supplied the place of private property. To deprive anyone of what he had thus seized became an act of injustice. Which Cicero has explained on the bounds of good and evil, by comparing the world to a theater in which the seats are common property, yet every spectator claims that which he occupies for the time being as his own.

It must be admitted that some things are impossible to be reduced to a state of property, of which the sea affords us an instance both in its general extent and in its principal branches. The magnitude of the sea is such as to be sufficient for the use of all nations, to allow them without inconvenience and prejudice to each other the right of fishing, sailing, or any other advantage that element affords. The same may be said of air as common property, except that no one can use or enjoy it without at the same time using the ground over which it passes or rests. So that the amusement of fowling cannot be followed, except by permission, without trespassing upon the lands of some owner, over which the birds fly.

The next thing to be considered is the right that men have to the common use of things. At first sight there appears to be some inconsistency here, as it appears that the establishment of property has absorbed every right that springs from a state of things held in common. But this is by no means the case. In matters of extreme necessity, the original right of using things as if they had remained in common must be revived.

Upon this principle is built the maxim that if in a voyage provisions begin to fail, the stock of every individual ought to be produced for common consumption. For the same reason a neighboring house may be pulled down to stop the progress of a fire, or the cables or nets in which a ship is entangled may be cut if it cannot otherwise be disengaged. Plato allows anyone to seek water from his neighbor’s well after having dug to a certain depth in his own without effect. Solon limits the depth to forty cubits, upon which Plutarch remarks that he intended by this to relieve necessity and difficulty but not to encourage sloth.

It is upon the same foundation of common right that a free passage through countries, rivers, or over any part of the sea which belongs to some particular people ought to be allowed to those who require it for the necessary occasions of life, whether those occasions be in quest of settlements after being driven from their own country, or to trade with a remote nation, or to recover by just war their lost possessions. The same reason prevails here as in the cases above named. Property was originally introduced with a reservation of that use which might be of general benefit and not prejudicial to the interest of the owner. This intention was evidently entertained by those who first devised the separation of the bounteous gifts of the creator into private possessions.

The fears that any power entertains from a multitude in arms passing through its territories do not form such an exception as can do away the rule already laid down. It is not proper or reasonable that the fears of one party should destroy the rights of another. Nor is it a proper reason to assign for a refusal to say that another passage may be found, as every other power might allege the same. By such means the right of passage would be entirely defeated. The request of a passage by the nearest and most commodious way, without doing injury and mischief, is a sufficient ground for it to be granted.

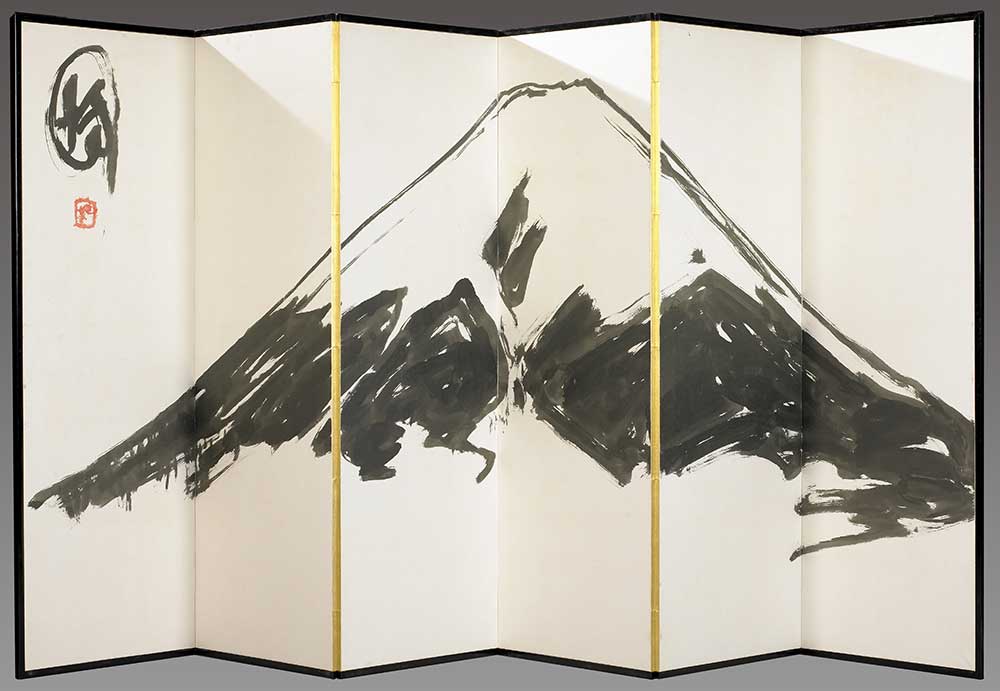

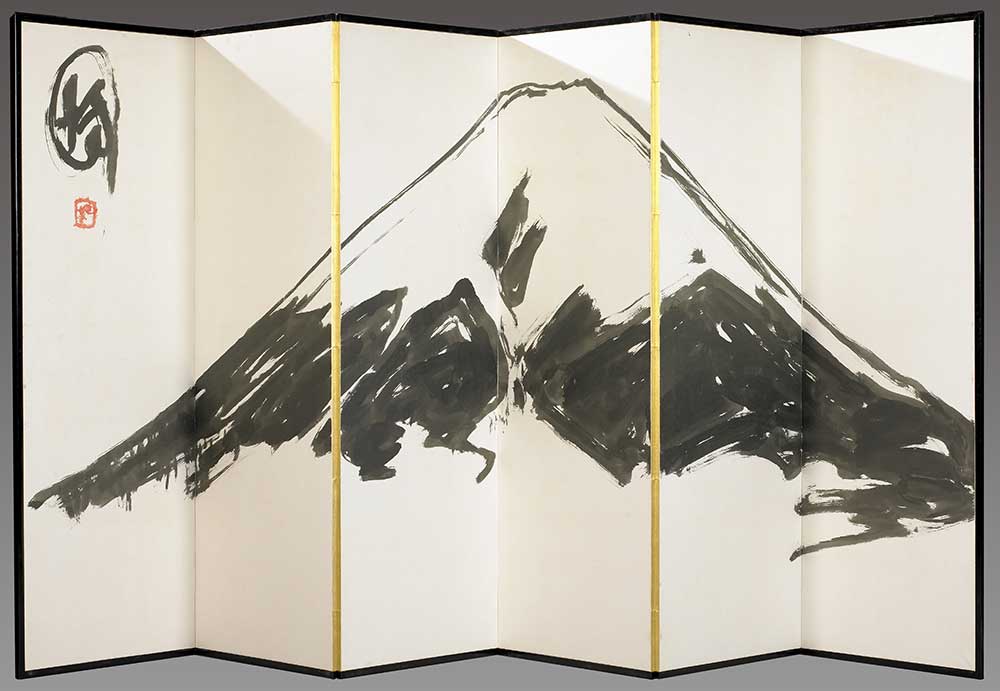

Pilgrimage to Mount Fuji, by Yoshida Hiroshi, c. 1925. Rijksmuseum.

A permanent residence should not be refused to foreigners who, driven from their own country, seek a place of refuge. But then it is only upon condition that they submit to the established laws of the place and avoid every occasion of exciting tumult and sedition. To drive away refugees, says Strabo, from Eratosthenes, is acting like barbarians; and a conduct like this in the Spartans was also condemned. Saint Ambrose passes the same sentence of condemnation on those powers who refuse all admission to strangers. Yet settlers of this description have no right to demand a share in the government. A proposal of this kind made by the Minyans to the Lacedaemonians, who had received them, is very properly considered by Herodotus as insolent and unreasonable.

It is indeed but an act of common humanity in a sovereign to allow strangers, at their request, liberty to reside on any waste or barren lands within his dominions, still reserving to himself all the rights of sovereignty. Seven hundred acres of barren and uncultivated land, as Servius observes, were given by the native Latins to the Trojans. Dio Chrysostom says that those who cultivate wastelands commit no crime of trespass. The refusal of this privilege made the Ansibarians exclaim, “The firmament over our heads is the mansion of the deity; the earth was given to man; and what remains unoccupied lies in common to all.”

From The Rights of War and Peace. Born in 1583 to a prosperous family in Delft, Grotius worked as a jurist and was appointed attorney general of Holland before being named pensionary of Rotterdam in 1613. Five years later he and his colleagues were ousted by Calvinist fundamentalists, and he was sentenced to life imprisonment. Allowed access to books and outside communication, he is said to have orchestrated his 1621 escape by hiding in a trunk sent by his wife under the pretext of removing his books. After reuniting with his family in Paris, Grotius wrote this three-volume treatise on international law.

Back to Issue