All men recognize the right of revolution, that is, the right to refuse allegiance to, and to resist, the government, when its tyranny or its inefficiency are great and unendurable.

—Henry David Thoreau, 1849All Men Would Be Tyrants if They Could

John and Abigail Adams compare notes on the American Revolution.

Braintree, Massachusetts, March 31

Abigail Adams to John Adams:

I wish you would ever write me a letter half as long as I write you, and tell me, if you may, where your fleet has gone, what sort of defense Virginia can make against our common enemy, whether it is so situated as to make an able defense. Are not the gentry lords and the common people vassals? Are they not like the uncivilized vassals Britain represents us to be? I hope their riflemen, who have shown themselves very savage and even bloodthirsty, are not a specimen of the generality of the people. I am willing to allow the colony great merit for having produced a Washington, but they have been shamefully duped by a Dunmore.

I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for liberty cannot be equally strong in the breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow creatures of theirs. Of this I am certain, that it is not founded upon that generous and Christian principle of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us.

Do not you want to see Boston? I am fearful of the smallpox, or I should have been in before this time. I got Mr. Crane to go to our house and see what state it was in. I find it has been occupied by one of the doctors of a regiment; very dirty, but no other damage has been done to it. The few things which were left in it are all gone. I look upon it as a new acquisition of property—a property which one month ago I did not value at a single shilling, and would with pleasure have seen it in flames.

The town in general is left in a better state than we expected—more owing to a precipitate flight than any regard to the inhabitants—though some individuals discovered a sense of honor and justice and have left the rent of the houses in which they were for the owners, and the furniture unhurt, or, if damaged, sufficient to make it good. Others have committed abominable ravages. The mansion house of your president is safe, and the furniture unhurt; while the house and furniture of the solicitor general have fallen a prey to their own merciless party. Surely the very fiends feel a reverential awe for virtue and patriotism, while they detest the parricide and traitor.

I long to hear that you have declared an independency. And, by the way, in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.

That your sex are naturally tyrannical is a truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute, but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of master for the more tender and endearing one of friend. Why then not put it out of the power of the vicious and the lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity? Men of sense in all ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the vassals of your sex; regard us then as beings placed by Providence under your protection, and in imitation of the Supreme Being make use of that power only for our happiness.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, April 14

John Adams to Abigail Adams:

You justly complain of my short letters, but the critical state of things and the multiplicity of avocations must plead my excuse. You ask where the fleet is? The enclosed papers will inform you. You ask what sort of defense Virginia can make? I believe they will make an able defense. Their militia and minutemen have been some time employed in training themselves, and they have nine battalions of regulars, as they call them, maintained among them under good officers at the Continental expense. They have set up a number of manufactories of firearms which are busily employed. They are tolerably supplied with powder and are successful and assiduous in making saltpeter. Their neighboring sister, or rather daughter, colony of North Carolina, which is a warlike colony and has several battalions at the Continental expense, as well as a pretty good militia, are ready to assist them, and they are in very good spirits and seem determined to make a brave resistance. The gentry are very rich, and the common people very poor. This inequality of property gives an aristocratical turn to all their proceedings, and occasions a strong aversion in their patricians to “Common Sense.”

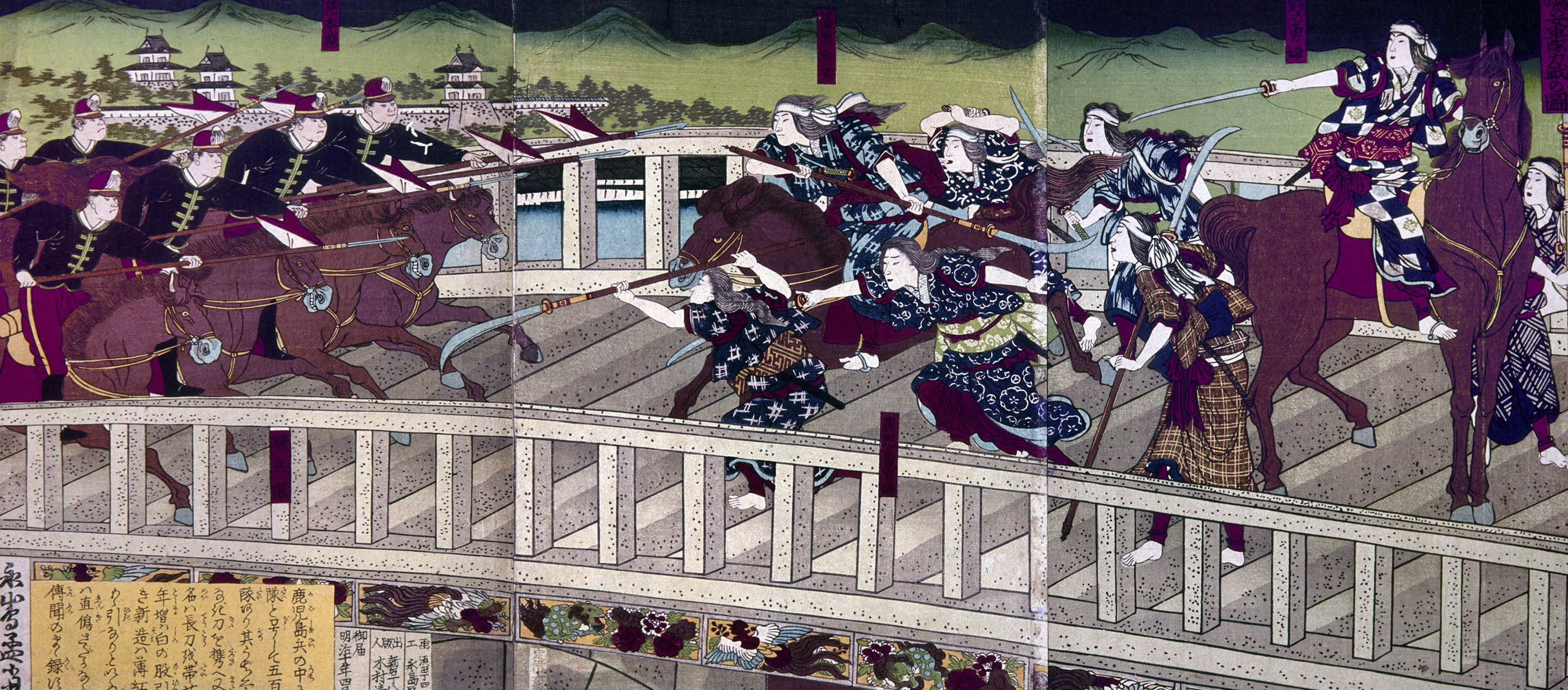

Women from Kyushu fighting against government cavalry during the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877, by Nagayama Umosai. Saigo Takamori led the revolt against the Meiji emperor; ten years prior he had helped to restore the imperial system. The Granger Collection.

You give me some pleasure by your account of a certain house in Queen Street. I had burned it long ago in imagination. It rises now to my view like a phoenix. What shall I say of the solicitor general? I pity his pretty children. I pity his father and his sisters. I wish I could be clear that it is no moral evil to pity him and his lady. Upon repentance, they will certainly have a large share in the compassions of many. But let us take warning and give it to our children. Whenever vanity and gaiety, a love of pomp and dress, furniture, equipage, buildings, great company, expensive diversions, and elegant entertainments get the better of the principles and judgments of men or women, there is no knowing where they will stop, nor into what evils, natural, moral, or political, they will lead us.

As to your extraordinary code of laws, I cannot but laugh. We have been told that our struggle has loosened the bonds of government everywhere, that children and apprentices were disobedient, that schools and colleges were grown turbulent, that Indians slighted their guardians and Negroes grew insolent to their masters. But your letter was the first intimation that another tribe, more numerous and powerful than all the rest, were grown discontented. This is rather too coarse a compliment, but you are so saucy I won’t blot it out. Depend upon it, we know better than to repeal our masculine systems. Although they are in full force, you know they are little more than theory. We dare not exert our power in its full latitude. We are obliged to go fair and softly, and in practice you know we are the subjects. We have only the name of masters, and rather than give up this, which would completely subject us to the despotism of the petticoat, I hope General Washington and all our brave heroes would fight; I am sure every good politician would plot, as long as he would, against despotism, empire, monarchy, aristocracy, oligarchy, or ochlocracy. A fine story, indeed! I begin to think the ministry as deep as they are wicked. After stirring up Tories, land jobbers, trimmers, bigots, Canadians, Indians, Negroes, Hanoverians, Hessians, Russians, Irish Roman Catholics, Scottish renegades, at last they have stimulated the ladies to demand new privileges and threaten to rebel.

John Adams and Abigail Smith Adams

From their letters. Abigail posted her letter only two weeks after the British evacuated their troops from Boston and almost one year after the Battles of Lexington and Concord signaled the beginning of the American Revolution. It had been this event that prompted John once again to leave his family for Philadelphia, where he served in the Second Continental Congress, sitting on more than ninety committees and chairing twenty-five. Benjamin Rush wrote of Adams, “Every member of Congress in 1776 acknowledged him to be the first man in the House.”