Women grading vanilla beans, Sambava, Madgascar, 2001. Photograph by Jonathan Talbot, World Resources Institute.

Cultivating vanilla is an intricate and laborious process from start to finish. That’s the reason it’s the second most expensive spice in the world, right after saffron.

All the vanilla orchids bloom in the month of March, with pale yellow, white, or green blossoms that smell faintly spicy, like cinnamon. The flowers only last a few hours, opening in the morning and shriveling by noon. Although vanilla orchids contain both male parts (the anther, which creates pollen) and female parts (the stigma, which receives pollen), these organs are separated by a thin membrane that seems to prevent the plant from self-pollinating. Botanists believe the plant is pollinated by native animals but are uncertain which ones. For many years, a tiny insect known as the Melipona bee was thought to be the flower’s pollinator. But recent research—performed by a team of graduate students who sat on platforms in the jungle canopy to watch wild vanilla orchids bloom—saw many different types of bees, ants, hummingbirds and bats visit the flowers. But none of them showed signs of pollinating. In all likelihood, it might be several of these visitors that guarantee the plant’s fertilization.

In the nineteenth century, when the plant was taken outside of Mexico, it lacked the native pollinators necessary for natural fertilization. It was a Belgian botanist named Charles Morren, working with a greenhouse specimen, who first made this link in 1839. He noted “the absence of the species of insect which nature has doubtless given to the climate of Mexico to effect in this latter region a fecundation.” To fertilize a vanilla plant, he wrote, you needed to do it by hand: “It is thus necessary to raise the velamen or to cut it when the plant is to be fecundated, and to place in direct contact the pollen and the stigmatic surface.” He went on to note: “The fecundation never fails.”

If you’re confused by Morren’s instructions, don’t worry, you’re not the only one. The single line he wrote about this extremely delicate process baffled botanists around the world. When they attempted to follow his instructions, they had spotty results at best. It’s actually not Morren’s method that’s used to hand-pollinate vanilla today. We use the method of the unlikely hero of nineteenth-century botany, Edmond Albius.

Edmond was born in about 1829, a slave on Île de Bourbon. His mother, Mélise, died in childbirth, and he never met his father, Pamphile, who passed away when Edmond was nineteen. When he was old enough, Edmond was sent by his mistress to work at the estate of her brother, Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont, who was known around the island for his skills in botany and horticulture. Bellier-Beaumont was the plantation owner who had kept a vanilla vine growing on his property for twenty years.

Somebody recognized that Edmond was bright, although it is unclear whether it was his former mistress or his new master. Bellier-Beaumont soon invited Edmond to accompany him on his rounds of his plantation. Of Edmond, he wrote, “This young black boy became my constant companion.” It was said he instilled a passion for botany in Edmond.

Edmond spent hours studying the botanical samples on the plantation. One day, or over the course of several days, Edmond tinkered with the vanilla blossoms that would not pollinate. They had become a source of concern for his master. Perhaps he sought out this challenge on his own; perhaps he was tasked with it. We’ll probably never know. What we do know is that, in the rising heat of a Réunion morning in 1841, Edmond developed the technique to pollinate vanilla that is still used today: he used a thin stick, a bit larger than a toothpick, to split the tubelike side of the flower, exposing the anther sac and the stigma, as well as the thin membrane that separated them. He lifted the membrane up and back, both exposing the stigma and causing the anther sac to shift upward. The anther sac touched the stigma, but just to make sure they connected, Edmond pushed them together with his thumb and forefinger.

The procedure of smashing together the male and female parts of the orchid is known today as “the marriage.” If the marriage is successful, the thick green base of the flower swells almost immediately. The swollen base matures into a green fingerlike seedpod—a fruit—that ripens yellow and eventually splits at the end. It would be ready to harvest nine months later, much like a human baby.

Bellier-Beaumont was strolling through his plantation with Edmond one day when he noticed with astonishment two vanilla pods ripening on the vine. Edmond piped up and said he did it. I bet the boy was proud; perhaps Bellier-Beaumont was, too. Edmond, only twelve years old, would change the world’s vanilla industry forever.

Rather than keep Edmond’s hand-pollination method secret, Bellier-Beaumont invited the heads of other local plantations over for a demonstration. Bellier-Beaumont made no attempt to claim the idea as his own. Edmond was celebrated in his time for his discovery: one source praised him as “ingenious.” His technique spread all over the island, and then to the neighboring islands of the Seychelles and Madagascar. The vanilla beans that grow in this region, thanks to Edmond’s efforts, are often called Bourbon vanilla—named after the Île de Bourbon.

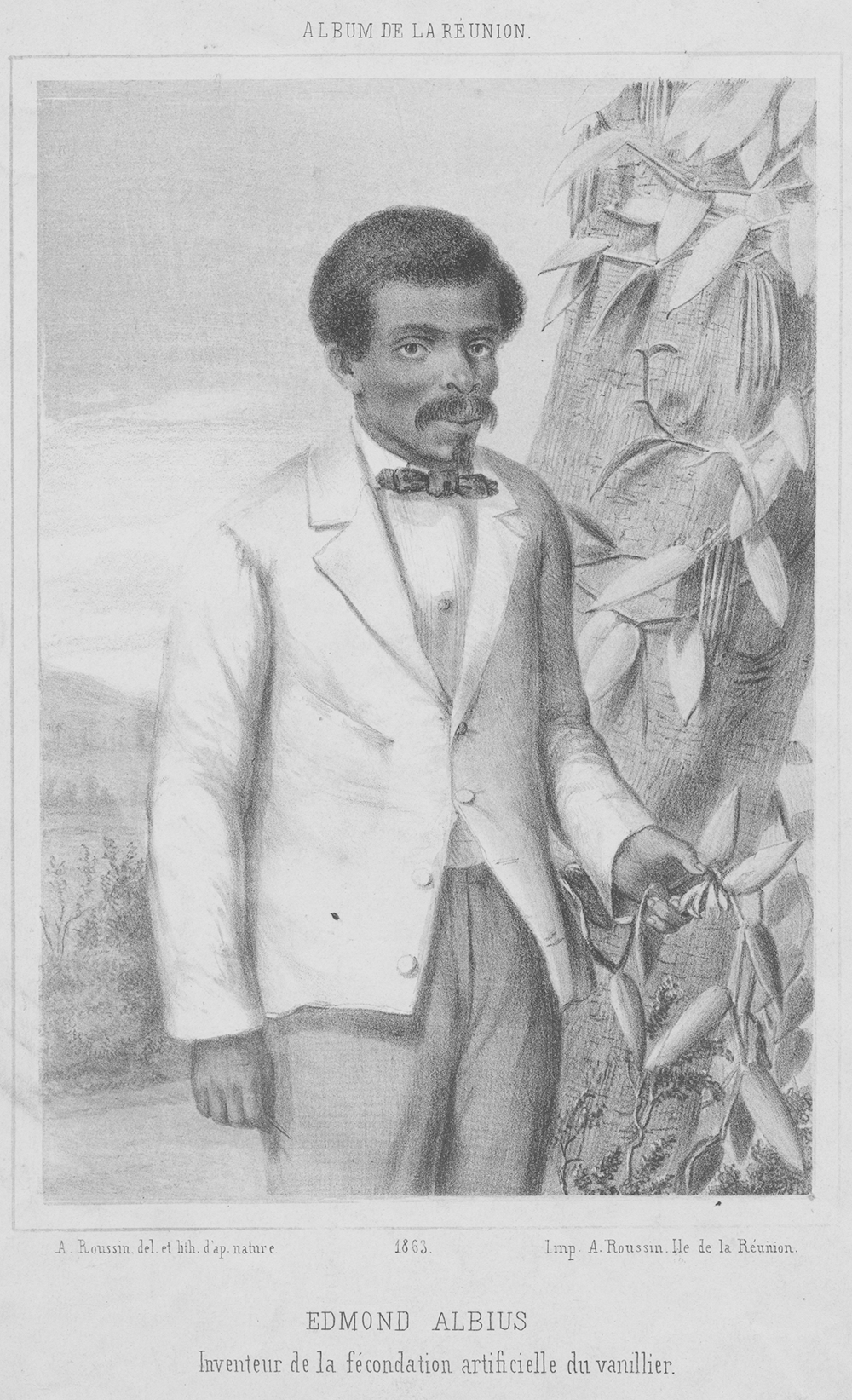

An 1847 daguerreotype—the earliest commercial photographic process—shows Edmond at eighteen, snappily if simply dressed in light, tight-fitting trousers and a boxy, slightly darker coat. He stares into the camera wide-eyed, looking more lanky teen than revolutionary botanist. Shortly after this photo was taken, Edmond would be freed. All slaves in the colony were emancipated at the end of 1848, but Bellier-Beaumont granted Edmond his freedom six months earlier. Edmond—who soon after took or was given the last name Albius—moved from the isolated plantation to the city of Saint-Denis, but life in the racially charged atmosphere of post-emancipation Réunion proved difficult. He desperately looked for work, with little success. Albius, after all, lacked a formal education—and it seemed that Bellier-Beaumont’s tutelage accounted for nothing in the minds of potential employers. Eventually Albius took a job doing manual labor, the only sort of work deemed fit for a former slave. Imagine how frustrated Albius must have been, and his situation would only get worse. Edmond was involved in a robbery, the details of which have been lost to history, but it seemed that he was either desperate for money or naive enough to be taken advantage of. He served more than two years’ hard labor before petitions from his old master secured his release.

Bellier-Beaumont actively championed for Albius, and did all he could to ensure that Albius would be recognized as the father of the vanilla industry in Réunion—which became the island’s major cash crop within Albius’ lifetime. Bellier-Beaumont wrote impassioned letters to guarantee that Albius was included in the seminal historical encyclopedia L’Album de l’Île de la Réunion. He defended Albius’ honor as the original inventor of the hand-pollination method when his credibility was doubted: some claimed that Edmond had previous knowledge of Morren’s workings in Belgium, while Bellier-Beaumont maintained that Albius came to his realization independently.

There was talk that wealthy planters, rich from the now-abundant vanilla crop, would provide a yearly salary for Albius. It never came to pass. After prison, for lack of other opportunities, he lived the rest of his life by Bellier-Beaumont’s charity, on a plot of land on his plantation. I wonder if Bellier-Beaumont thought that Albius would use it to grow food or to continue his botanical work. But the hand-pollination method was Albius’s first and last known accomplishment. Edmond Albius died on August 26, 1880, at the age of fifty-one; his obituary read: “It was a destitute and miserable end.”

Excerpted from Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine by Sarah Lohman. Copyright © 2016 by Sarah Lohman. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.