The greatest veneration one can show the law is to keep a watch on it.

—Nadine Gordimer, 1971Money Talks

John Paul Stevens unpacks freedom of speech.

Let us start from the beginning. The court invokes “ancient First Amendment principles” and original understandings to defend today’s ruling, yet it makes only a perfunctory attempt to ground its analysis in the principles or understandings of those who drafted and ratified the amendment. Perhaps this is because there is not a scintilla of evidence to support the notion that anyone believed it would preclude regulatory distinctions based on the corporate form. To the extent that the framers’ views are discernible and relevant to the disposition of this case, they would appear to cut strongly against the majority’s position.

This is not only because the framers and their contemporaries conceived of speech more narrowly than we now think of it, but also because they held very different views about the nature of the First Amendment right and the role of corporations in society. Those few corporations that existed at the founding were authorized by grant of a special legislative charter. Corporate sponsors would petition the legislature, and the legislature, if amenable, would issue a charter that specified the corporation’s powers and purposes and “authoritatively fixed the scope and content of corporate organization,” including “the internal structure of the corporation.” Corporations were created, supervised, and conceptualized as quasi-public entities, “designed to serve a social function for the state.” It was “assumed that they were legally privileged organizations that had to be closely scrutinized by the legislature because their purposes had to be made consistent with public welfare.” The individualized charter mode of incorporation reflected the “cloud of disfavor under which corporations labored” in the early years of this nation. In A History of American Law, Lawrence M. Friedman writes, “The word soulless constantly recurs in debates over corporations…Corporations, it was feared, could concentrate the worst urges of whole groups of men.” Thomas Jefferson famously fretted that corporations would subvert the republic. General incorporation statutes, and widespread acceptance of business corporations as socially useful actors, did not emerge until the 1800s.

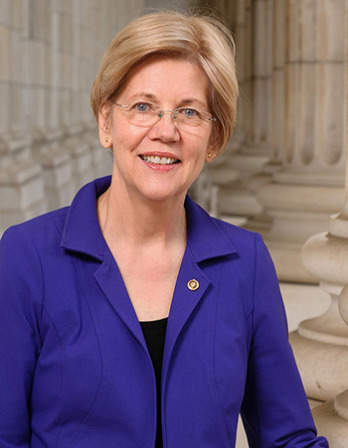

Signing of the Constitution, by Howard Chandler Christy, 1940. U.S. Capitol.

The framers thus took it as a given that corporations could be comprehensively regulated in the service of the public welfare. Unlike our colleagues, they had little trouble distinguishing corporations from human beings, and when they constitutionalized the right to free speech in the First Amendment, it was the free speech of individual Americans that they had in mind. While individuals might join together to exercise their speech rights, business corporations, at least, were plainly not seen as facilitating such associational or expressive ends. Even “the notion that business corporations could invoke the First Amendment would probably have been quite a novelty.” In light of these background practices and understandings, it seems to me implausible that the framers believed “the freedom of speech” would extend equally to all corporate speakers, much less that it would preclude legislatures from taking limited measures to guard against corporate capture of elections.

The court observes that the framers drew on diverse intellectual sources, communicated through newspapers, and aimed to provide greater freedom of speech than had existed in England. From these (accurate) observations, the court concludes that “the First Amendment was certainly not understood to condone the suppression of political speech in society’s most salient media.” This conclusion is far from certain, given that many historians believe the framers were focused on prior restraints on publication and did not understand the First Amendment to “prevent the subsequent punishment of such publications as may be deemed contrary to the public welfare.” Yet even if the majority’s conclusion were correct, it would tell us only that the First Amendment was understood to protect political speech in certain media. It would tell us little about whether the amendment was understood to protect general treasury electioneering expenditures by corporations, and to what extent.

As a matter of original expectations, then, it seems absurd to think that the First Amendment prohibits legislatures from taking into account the corporate identity of a sponsor of electoral advocacy. As a matter of original meaning, it likewise seems baseless—unless one evaluates the First Amendment’s “principles” or its “purpose” at such a high level of generality that the historical understandings of the amendment cease to be a meaningful constraint on the judicial task. This case sheds a revelatory light on the assumption of some that an impartial judge’s application of an originalist methodology is likely to yield more determinate answers, or to play a more decisive role in the decisional process, than his or her views about sound policy.

In fairness, our campaign finance jurisprudence has never attended very closely to the views of the framers, whose political universe differed profoundly from that of today. We have long since held that corporations are covered by the First Amendment, and many legal scholars have long since rejected the concession theory of the corporation. But “historical context is usually relevant,” and in light of the court’s effort to cast itself as guardian of ancient values, it pays to remember that nothing in our constitutional history dictates today’s outcome. To the contrary, this history helps illuminate just how extraordinarily dissonant the decision is.

John Paul Stevens

From his dissenting opinion in Citizens United v. FEC. In the wake of Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion—which “rejected the argument that political speech of corporations or other associations should be treated differently under the First Amendment”—Barack Obama argued the decision would allow “special interests, including foreign corporations, to spend without limit in our elections.” Newly legal super PACs reported expenditures of $609 million during the 2012 U.S. presidential election; these reached $1.1 billion during the 2016 election.