Zephyrus: Never did I see a more magnificent procession on the sea since I was born and began to blow. But you—did you not see it, Notus?

Notus: What is this procession you talk of, Zephyrus, or who were the processionists?

Zephyrus: You have missed a most delicious spectacle, the likes of which you may never see again.

Notus: Yes, for I was employed in the neighborhood of the Red Sea, and indeed, I blow over part of India, as much of the country as stretches along the sea coast. I know, therefore, nothing of what you speak.

Zephyrus: But you know Agenor of Sidon?

Notus: Yes, the father of Europa. What, then?

Zephyrus: It is about herself I will relate to you a story.

Notus: It is not, is it, that Zeus has been for a long time the girl’s lover? For that I knew quite a long while ago.

Zephyrus: You are, then, aware of the amour. But listen now to the sequel. Europa had gone down to the shore in sportive mood, taking with her companions of her own age. And Zeus, making himself like a bull, began to sport with them, seeming a very handsome creature, for he was perfectly white, and had beautifully crumpled horns, and was tame and quiet in look. He began, then, as he was, to frolic about upon the shore and to bellow most sweetly, so that Europa ventured even to mount him. And as soon as this was done, Zeus started off with her at a running pace toward the sea, and plunging in, began to swim. But she, very much terrified at the occurrence, with her left hand clinging to his horn, that she might not slip off, while with the other she held together her long flowing dress, blown about by the wind.

Watson and the Shark, by John Singleton Copley, 1778. National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Notus: That was a charming spectacle, Zephyrus, you witnessed, and amorous—Zeus swimming, carrying his beloved.

Zephyrus: Yet what followed was far more delightful, Notus. For the sea from that moment was without a ripple and, attracting a perfect calm, showed itself smooth and unruffled. We, however, keeping quiet, followed, being no more than mere spectators of what was happening; and the Loves, hovering a little above the sea so as at times to graze the water with the tips of their feet, with lighted torches sang together the hymeneal song; while the Nereids, emerging from the sea, rode by their side upon dolphins, clapping their hands, most of them half-naked. Then, too, the whole tribe of Tritons—and whatever else of the sea dwellers is not terrible to the sight—all led their dances round the girl. Poseidon, indeed, mounting upon his chariot, and with Amphitrite riding at his side, led the way, clearing the way for his swimming brother. To crown all, two Tritons were bearing Aphrodite, who reclined upon a shell and scattered all sorts of flowers before the bride. This took place all the way from Phoenicia as far as Crete. But, when he had set foot on the island, the bull was no longer to be seen. Then Zeus, taking her by the hand, conducted Europa to the cave of Dicte, blushing and with eyes cast down, for now she knew to what she was being led. And we, plunging in, set to work to put the sea in commotion, one in one part, and another in another.

Notus: O fortunate Zephyrus, to have seen such a sight! But I, for my part, had to satisfy my eyes with elephants, griffins, and black men.

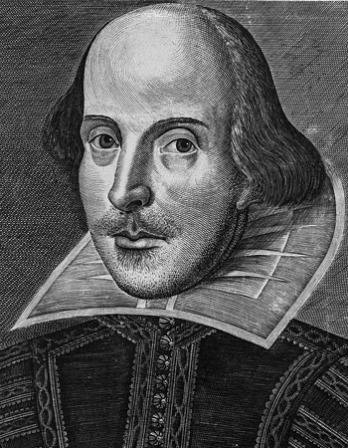

From The Dialogs of the Sea Gods. Born around 120, Lucian was apprenticed to a sculptor in his native Syria and became a successful rhetorician in Italy and Gaul before beginning his writing career in Athens. William Shakespeare drew inspiration from one of Lucian’s plays for Timon of Athens; Ben Jonson took the idea that Helen of Troy “launched a thousand ships” from The Dialogs of the Dead; and Lucian’s story “The Lover of Lies” served as the basis for Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.”

Back to Issue