To enter upon a deliberate argument to prove that baseball is our national game; that it has all the attributes of American origin, American character, and unbounded public favor in America, seems a work of supererogation. It is to undertake the elucidation of a patent fact; the sober demonstration of an axiom; it is like a solemn declaration that two plus two equals four.

I claim that baseball owes its prestige as our national game to the fact that, as no other form of sport, it is the exponent of American courage, confidence, combativeness; American dash, discipline, determination; American energy, eagerness, enthusiasm; American pluck, persistency, performance; American spirit, sagacity, success; American vim, vigor, virility.

Baseball is the American game par excellence, because its playing demands brain and brawn, and American manhood supplies these ingredients in quantity sufficient to spread over the entire continent.

No man or boy can win distinction on the ball field who is not, as man or boy, an athlete, possessing all the qualifications which an intelligent, effective playing of the game demands. Having these, he has within him the elements of pronounced success in other walks of life. In demonstration of this broad statement of fact, one needs only to note the brilliant array of statesmen, judges, lawyers, preachers, teachers, engineers, physicians, surgeons, merchants, manufacturers, men of eminence in all the professions and in every avenue of commercial and industrial activity, who have graduated from the ball field to enter upon honorable careers as American citizens of the highest type, each with a sane mind in a sound body.

It seems impossible to write on this branch of the subject—to treat of baseball as our national game—without referring to cricket, the national field sport of Great Britain and most of her colonies. Every writer on this theme does so. But, in instituting a comparison between these games of the two foremost nations of earth, I must not be misunderstood. Cricket is a splendid game—for Britons. It is a genteel game, a conventional game, and our cousins across the Atlantic are nothing if not conventional. They play cricket because it accords with the traditions of their country so to do, because it is easy and does not overtax their energy or their thought. They play it because they like it and it is the proper thing to do. Their sires, and grandsires, and great-grandsires played cricket—why not they? They play cricket because it is their national game, and every Briton is a patriot. They play it persistently, and they play it well. I have played cricket and like it. There are some features about that game which I admire more than I do some things about baseball.

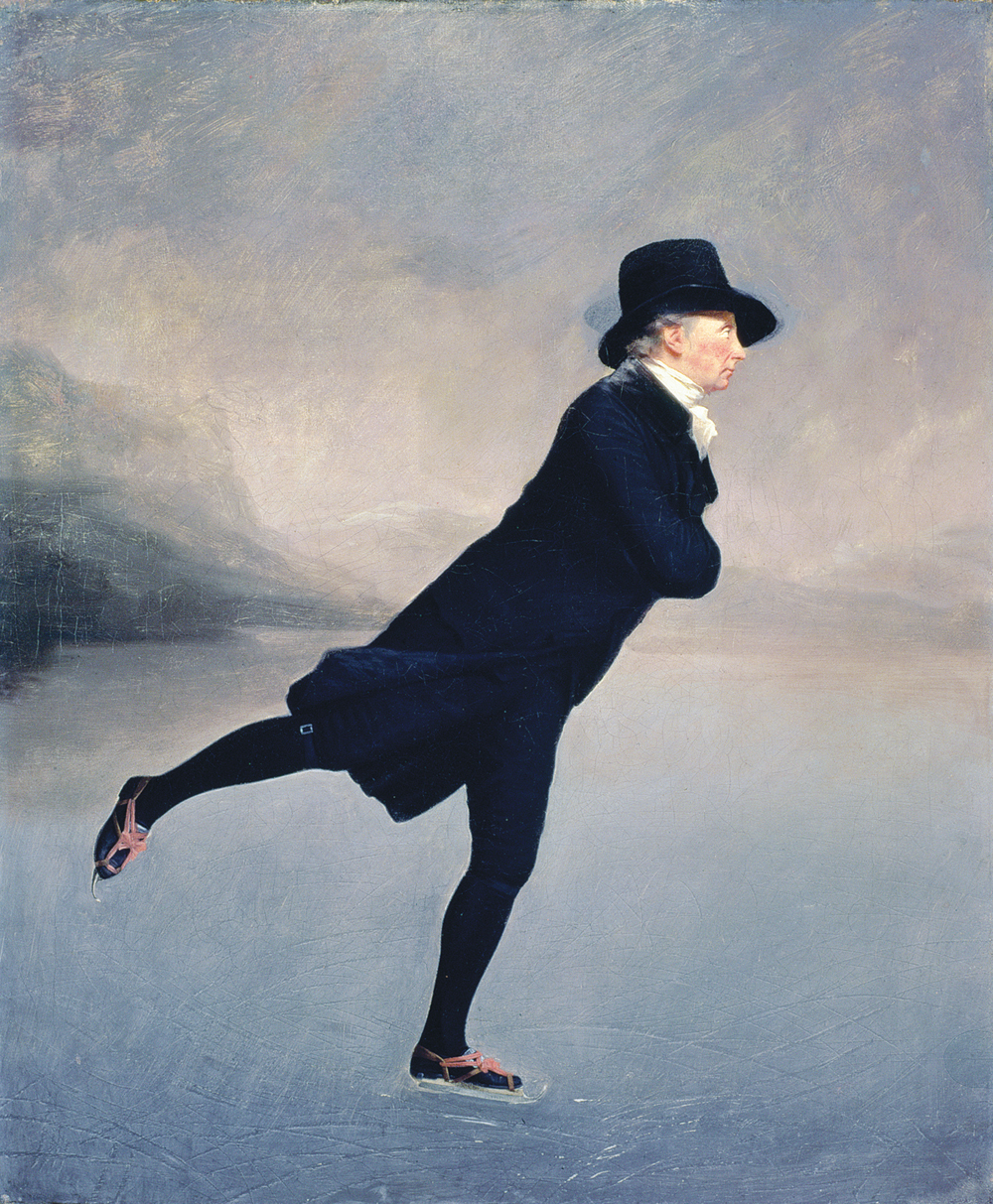

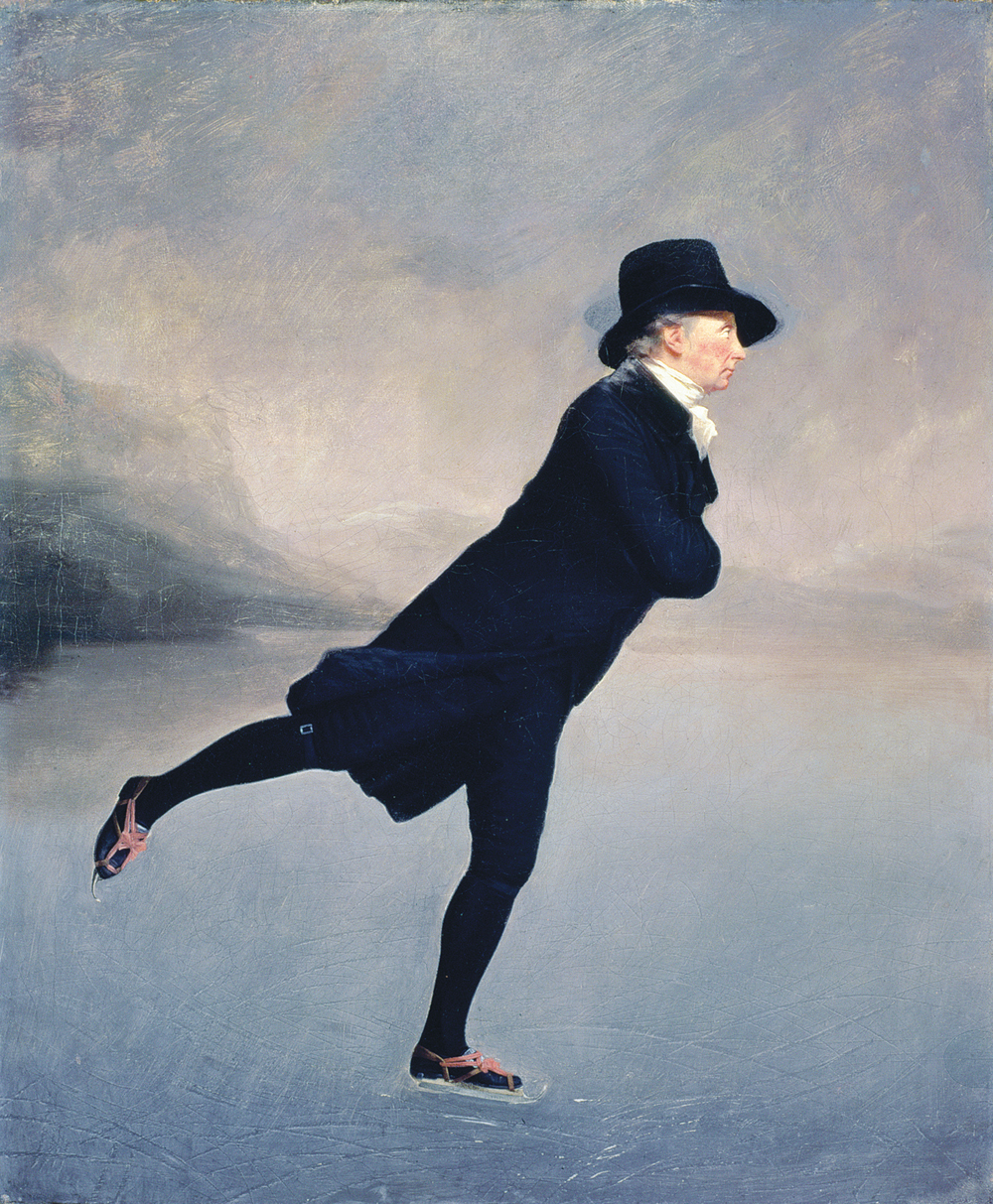

Rev. Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch, by Sir Henry Raeburn, c. 1781. Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland.

But cricket would never do for Americans; it is too slow. It takes two and sometimes three days to complete a first-class cricket match, but two hours of baseball is quite sufficient to exhaust both players and spectators. An Englishman is so constituted by nature that he can wait three days for the result of a cricket match, while two hours is about as long as an American can wait for the close of a baseball game—or anything else, for that matter. The best cricket team ever organized in America had its home in Philadelphia—and remained there. Cricket does not satisfy the red-hot blood of young or old America.

The genius of our institutions is democratic; baseball is a democratic game. The spirit of our national life is combative; baseball is a combative game. We are a cosmopolitan people, knowing no arbitrary class distinctions, acknowledging none. The son of a President of the United States would as soon play ball with Patsy Flannigan as with Lawrence Lionel Livingstone, provided only that Patsy could put up the right article. Whether Patsy’s dad was a banker or boilermaker would never enter the mind of the White House lad. It would be quite enough for him to know that Patsy was up in the game.

I have declared that cricket is a genteel game. It is. Our British cricketer, having finished his day’s labor at noon, may don his negligee shirt, his white trousers, his gorgeous hosiery, and his canvas shoes, and sally forth to the field of sport with his sweetheart on one arm and his cricket bat under the other, knowing that he may engage in his national pastime without soiling his linen or neglecting his lady. He may play cricket, drink afternoon tea, flirt, gossip, smoke, take a whisky and soda at the customary hour, and have a jolly, conventional good time, don’t you know?

Not so the American ball player. He may be a veritable Beau Brummel in social life. He may be the swellest swell of the smart set in swelldom; but when he dons his baseball suit, he says goodbye to society, doffs his gentility, and becomes—just a ball player! He knows that his business now is to play ball, and that first of all he is expected to attend to business. It may happen to be his business to slide; hence, forgetting his beautiful new flannel uniform, he cares not if the mud is four inches deep at the base he intends to reach. His sweetheart may be in the grandstand—she probably is—but she is not for him while the game lasts.

Cricket is a gentle pastime. Baseball is war! Cricket is an athletic sociable, played and applauded in a conventional, decorous, and English manner. Baseball is an athletic turmoil, played and applauded in an unconventional, enthusiastic, and American manner.

From America’s National Game. Spalding pitched for the Boston Red Stockings, afterward opening a sporting-goods store that became A.G. Spalding and Brothers. While managing the company and acting as president of the Chicago White Stockings, he led an around-the-world baseball tour in 1888–89. He died at the age of sixty-five in 1915 and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939.

Back to Issue