The true mission of American sports is to prepare young men for war.

—Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1952

Skating on the Wissahickon, by Johan Mengels Culverhouse, 1875. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Rogers, Morris K. Jesup and Maria DeWitt Jesup Funds, and Charles and Anita Blatt Gift, 1974.

I suffer from a seasonal illness that was once very common in Britain but is now rare. It still afflicts the Dutch, though, in the thousands. It strikes me like delirium, when the lakes nearby freeze over and the ice issues an imperative: Carpe diem! Get your skates on! Love, yawns, and suicides, they say, are all infectious. So is play, and skate fever is a highly contagious form. The industrious, beware.

In the Welsh hills where I live, years can pass without the waters freezing, but this one and last were both skating winters—a few precious days of frost and rapture. If joie de vivre could be distilled to one image alone, it would be a skating party sliding down the hill to wake the lake. Last year on a clear night, I skated with friends by moon- and starlight, lanterns scattered around the edge of the lake like fireflies, and we wore full evening dress plundered from charity shops: feathers, fascinators, and fake furs. Wrapped up and amazed, the wrigglers and rugglers (small children and puppies) stayed at the edge, near the soup and the wood fire on the lakeshore. Though the “ecstasy”—in its root “standing apart from”—comes from skating out to the lake’s center and farther to its far and silent shores, across the Zuiderzee.

This kind of joy is superfluous and therefore absolutely necessary. It is the deep meaning of revelry and play, as the historian Johan Huizinga wrote in his masterpiece Homo Ludens. Culture itself “arises in the form of play.” “Play cannot be denied. You can deny, if you like, nearly all abstractions: justice, beauty, truth, goodness, mind, God. You can deny seriousness, but not play.” Flemish paintings of ice merriment depict lovers and children and horse-drawn sleighs; the Dutch still hold carnivals on ice. In homage to Homo Ludens, we skated in the time between Christmas and New Year, honoring the play ethic rather than the work, the ludic revolution rather than the industrial, racing one another and improvising a new form of hockey with a skinny, squeaking rubber chicken. A local farmer came on skis, someone else tried to fly a kite, puppies slipped comically on the ice, and children slid and pushed each other over.

Ball Players, by George Catlin, c. 1841. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

Skating oscillates between the twin arts of conviviality and of solitude: you can join up with the carnivaliers for hot chocolate laced with brandy, then swing away on a trajectory of glorious freedom, a world apart (“All, alone, together,” wrote E.E. Cummings in his poem “skating”). One skating day this past year, I was circling the center of a lake and found my movement mirrored in the sky, as a bird of prey, similarly alone, was curious and circling overhead.

Wild skating, as opposed to rink skating, always suggests this twofoldness: the water which freezes and thaws, the crisp breath in and the steamy breath out, life above in the air and death below the ice. You swing a long arc out to the left and a curve back to the center; a long arc out to the right and a curve back to the center, each skate leaving slender S’s, cut into the ice like cold calligraphy. The twofoldness is an image of balance, a balance which, skaters know, comes best from movement.

Skating, diving, and dreaming are all forms of flying. “When to his feet the skater binds his wings …” wrote the aptly named poet Robert Snow, who is not to be confused with Robert Frost (“Style is the mind skating circles round itself as it moves”) or indeed with Samuel Taylor Coleridge (“The Frost performs its secret ministry,/Unhelped by any wind.”) The god Mercury was, according to Coleridge, the first maker of skates, and every skater has wings at their feet. The flight is compelling to watch: huge numbers of spectators turn out for ice races in Holland, and millions of people around the world watch figure-skating championships in the Winter Olympics—perhaps not so much for the element of competition but for the momentary quality of flight, of sheer grace. While out wild skating, the birds (accustomed to watching us trudge) hover and gaze at skaters as we humans become occasional flyers on the evanescent ice.

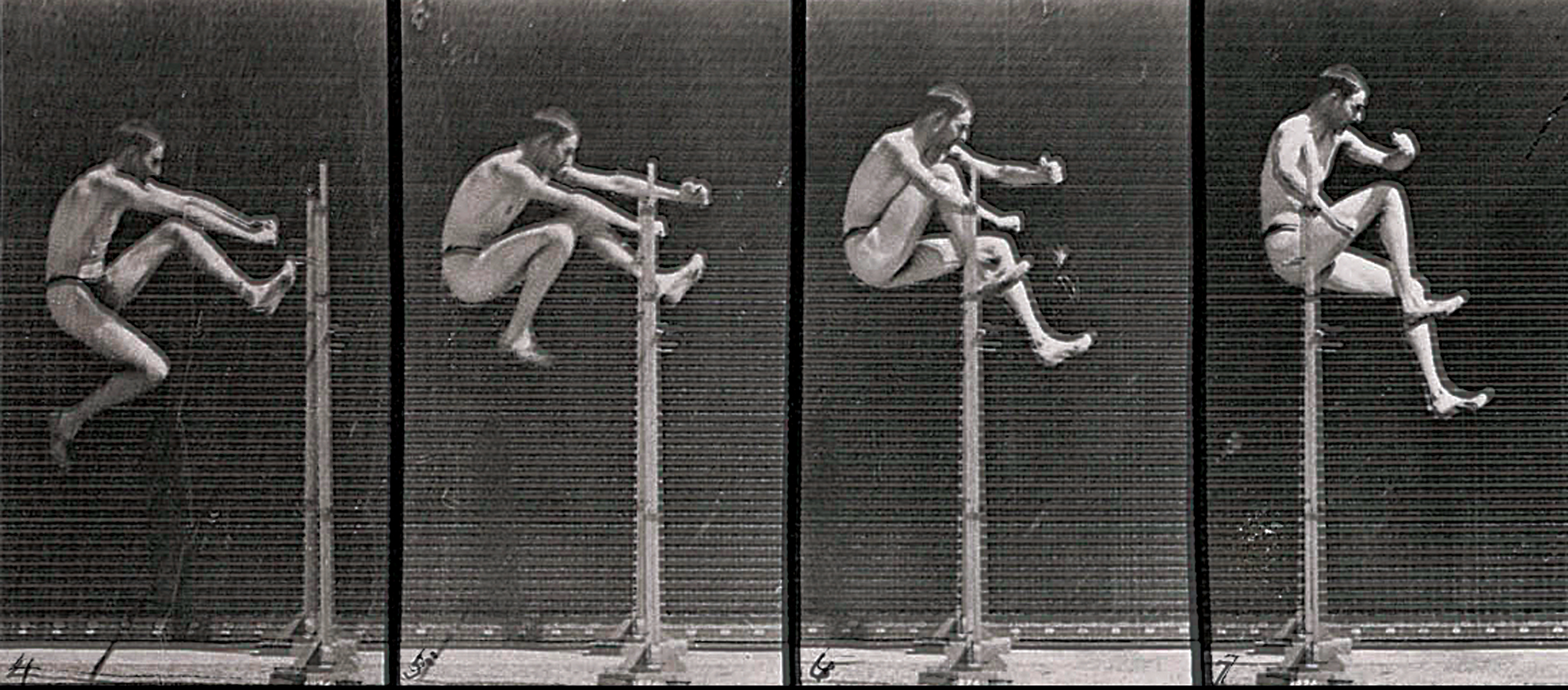

In the Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Winter Landscape with a Bird Trap, the sense of swift movement in the skaters is such that, about 450 years later, they look as if they’re moving. The eye jumps from figure to figure, each caught in a slightly different pose, the effect like the early animation “thumb cinema,” flip books which rely on the eye’s persistence of vision to give the impression of speed. “Peasant Bruegel,” as he has become known, paints the equality of ice games. This is an open carnival of the commons where even poverty cannot stifle the zest of play which steams through the boisterous carnivaliers with such immediacy you can almost hear them laughing.

People have been skating for thousands of years. Skates fashioned from the shank or rib bones of animals have been found throughout Scandinavia and Russia, including some thought to date back to 3000 bc. Similar finds have been made in Britain, where the first written record of skating occurs in a work by the twelfth-century monk, William Fitzstephen. Writing about the children of London attaching bones to their ankles, he observed, “They fly across the ice like birds… then attack each other until one falls down.” Some things never change.

The Dutch have the fullest known history of skating. First, ice skates were fashioned from animal ribs, which were drilled so they could be tied to boots, and then, beginning in the fourteenth century, they were made of iron runners fixed to wooden platforms. Skaters used poles to push themselves across the ice. Around a hundred years later, they invented the sharpened double-edged blade and threw away the poles, and by 1600 they were using steel blades. The patron saint of ice skating, St. Lidwina, is Dutch, while old ballads, describing the great frost and ice fair on the Thames in 1684, speak of:

The Rotterdam Dutchman, with fleet-cutting scates

To pleasure the crowd shows his tricks and his feats

Who, like a rope dance (for his sharp steels),

His brains and activity lies in his heels.

It is a playful history. A 1904 travel book, Holland, records winter traditions when “all the world is out on skates, on business or pleasure bent,” people pulling sleighs made from packing cases and “a freight of laughing babies.” Skating competitions “form the chief amusement of the winter.” And, as it appeared in Bruegel’s painting, ice skating was an inclusive sport, enjoyed by all classes, unlike the tendency elsewhere in Europe for it to be reserved for aristocracy.

About skating they were never wrong, the old masters. In Rembrandt’s Winter Landscape, for instance, a figure in the foreground puts on a pair of skates—which look like cow’s ribs—and all the figures are wrapped in the warmth of the painter’s kindness, so that they look as if they will never be cold again. For all the sheer fun in Bruegel’s Winter Landscape with a Bird Trap, there is perhaps a deeper hint that the birds are included for their traditional symbolic meaning, representing the human soul and suggesting that there is brevity in the revelry of ice and of life. Skating is as flitting as the flight of a bird. For bird or human, existence is as short as daylight in midwinter.

Man jumping, time-lapse photographs from the Animal Locomotion series, by Eadweard Muybridge, c. 1885. The Wellcome Trust, London.

The first Dutch artist to specialize in depicting winter ice revels was Hendrick Avercamp, working in the seventeenth century, and his paintings—with eel angling, games, and skaters falling on ice—hum with the playfulness that the Dutch, culturally, associate with ice. It is entirely fitting that the author of Homo Ludens was also Dutch.

The most festive of competitions is the skating race, the Elfstedentocht, the “Eleven-Towns Tour.” It was first formally held in January 1909 and has been revived only intermittently over the past century, because the 124-mile track will only freeze in the severest winters. The lower the temperatures remain, the higher the pitch of fever, as the excitement grows as to whether or not the race will happen. There is even a word in Dutch specifically for this expectation: Elfstedenkoorts, “Eleven-Towns-Tour Fever,” a near frenzy in any year, peaking when “It giet oan!”—“It is on!”—is announced. One in eight of the population—around two million people—turns out to cheer on as many as sixteen thousand skaters, and there are stalls selling hot chocolate and pea soup along the route. (The New York City Marathon attracts a similar number with usually more than double the amount of racers.) On the evening before the race, there is an enormous street party in Leeuwarden, where the race begins and ends, sometimes referred to as the “Eleven-Bars Tour,” an evening of booze, boasts, and bets.

Overriding the competitive element is camaraderie: something funny happened on the way to the finish line in 1956. Five people completed the race in tandem (“All, alone, together”), and the judges withheld the prize from them. Why so? Because in 1933 and 1940, there had been joint winners when the leaders chose not to compete but rather to hold hands, as they finished the race. The organizers forbade the practice after 1940, but the 1956 winners gloriously flouted the ruling and were disqualified. There are photographs of the five at the finishing line—faces of exhilaration and jubilation—skating for skating’s sake. This is the best advice from the masters of skating: skate generously, for mean-mindedness cuts no ice out here.

Their defiance hinted at the egalitarian history of their country’s skating and at the essential freedom of playfulness unbound by rules, and it resounded with the spirit of generosity, to share the pleasure. It is that spirit which prompts me to share not only the delight of wild skating, but to sketch out a beginner’s guide.

F irst, find some skates. You need stiff boots, the blades sharp. Near me, some twenty years ago, winter skating began when a local doctor collected a motley assortment of skates, among them a dainty Victorian pair, one pair of army-training boots with blades screwed to the soles—which is great for doing the involuntary splits but rubbish for doing straight lines—another pair of tough farm boots, loads of children’s skates from charity shops and garage sales, and a pair of Dutch speed skates. The good doctor induced a local outbreak of skate fever.

Next, find a place to skate. Rivers are a terrible idea, obviously, because ice freezes too unpredictably. Canals are also to be treated with very great caution—the overflow from drains makes the ice undependable. Fields that have flooded and then frozen are great, and there is no need to test the depth of the ice. Lakes are lovely, as the Romantics knew. Skating in the Lake District, Wordsworth at sixty was still a “crack skater,” according to his sister Dorothy. I don’t think she meant it as a pun.

So how do you test the depth of ice on lakes? Take a hammer and chisel, or a battery-operated drill or, if you’ll be lighting a fire, take a poker to heat up and make a hole in the ice. When you’ve drilled a hole, stick your finger in, and the ice should be three or four inches deep, a finger length. This means it should be skateable, but let me at this point introduce a basic rule of skating: be both bold and cautious. If in doubt, stay close to the edge. Don’t skate on snow unless you’re sure of the ice underneath.

Take a safety rope. If anyone goes through the ice, there’ll be a chance of hauling them out. Take another rope for playing with children, puppies, or sledges, and don’t let them use the safety rope. Bring lanterns—tea lights tucked into white baker’s paper bags glow like creamy magnolia flowers—and warm clothes, extra socks, and “second-skin” blister patches, not ordinary Band-Aids. Take a broom, too: if there has been a light snowfall, you can brush snow away while you go, and more importantly, a broom is good for novice skaters who can lean on it for support and—unlike a stick or a well-intentioned friend—the broom will not slip on the ice. Take food and drink and musical instruments. Tell kids not to throw stones or snowballs; it’s fun, but it trips skaters. For the same reason, tell puppies not to crap on the ice.

L ike most things in life, skating is best done openhearted. Trust each foot in turn, let your attention and your weight glide long on each leg. Lean forward into it all. Trust your wings. Trust the ice, too, but stay observant of its moves and cracks, try to read its history of thawing and refreezing and buckling. This is when skaters yearn for more precise language, for the distinct words for ice in Inuktitut, the Inuit language, because the words discriminate between how ice is formed, which in turn tells you how it will—or should—behave. And, for Inuit hunters out on the ice, how the ice behaves is that upon which your life depends. There are many traditional games in Inuit culture, and sports that are also ways of traveling—dog-sled and kayak racing, for example—but the harsh realities of climate demand that ice is taken seriously and identified precisely.

When I was in Igloolik, in the Canadian Arctic, I asked people about words for ice. I stopped writing by the time I’d noted thirty-three, accompanied by full descriptions. The following are just a handful of examples. Mark Ijjangiaq, an Inuk man from Igloolik, describes moving ice being dislodged from land-fast ice, leaving some of it cemented to the land-fast ice. This new addition is nipititaaq and is usually rough with pressure ridges. This ice pan in turn will move out but separate from the main block, and the terminology gets more precise still, for if this separate pan is high with pressure ridges, it is called ijukaqut. Uluangnait is when snow has fallen on newly formed ice and that ice has not yet become strong so the ice underneath is warmed and pushed underwater by snow. Then that ice is doubly warmed, by snow above and by water below. This, of course, is highly dangerous. There are at least eight terms for the stages of ice melt.

Horse race at the Atsuta shrine, Japan, from Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido (detail), by Ando Hiroshige, c. 1834. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

When I asked another elder of Igloolik, Michel Kopaaq Piugaattuk, for different words for snow, he reeled off fifteen, hardly pausing for breath. Fifteen entirely distinct words. Some academics have scorned the idea of a long lexicon of words for snow in Inuktitut, calling it a “vocabulary hoax” and claiming that there are not a large number of separate words for snow but rather terms compiled through a variety of prefixes and suffixes. I believe this is simply untrue, and rather overweening for those who do not speak Inuktitut to pretend they know Inuktitut better than Inuit elders. They are rich in knowledge, meat, and time, and generous with them all, remarks the anthropologist Hugh Brody.

The year has two generosities: that of harvest, as August augments into autumn, ripening and swelling, the other of white beginnings and open futures where all is possibility, wide as a frozen lake when you can no longer see its limits. A clean sheet of paper speaks of the same generosity, where nothing is prescripted and anything can begin. A wide-open day, too, when time stretches untrapped by schedule and offers opportunity, so spontaneity uncurls and basks in the extravagance of the open moment.

This is the generosity that Homo Ludens knows so well. The generosity at the heart of play: the spirit of excess, the sense of abundance, the figurative harvest of pleasure after work, the brimming possibilities of the extra and the gleefully unnecessary. The grace notes of life, arising in play.

L ast year, out skating, I saw sunlight, iridescent as it glanced the ice, dazzling and perfect. I saw moonlight, pale and gold, as the evening star rose. Sometimes the ice is black, so you can see the water, darkly dangerous below, and other times the surface is frosted white, with crystals all across the ice like strewn flowers.

Ice sharpens your thoughts, and out here everything is sharp: skate blades, frost, sunlight in your eyes—even the contrast between day and night is sharpened by cold. Summer has an incoherent lushness, warm and lolling, rolling over everything else, slurred. Winter has a cold coherence, exact and electric, compact as skates laced tight and sharp to the clean ice.

Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world: it gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel. The picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.

—Susan B. Anthony, 1896In the air I heard all the chatter and sounds of warm red life. Under the lake ice, though, the water boomed an eerie hollow moan, creaking below, a bassoon of ice, then a cello string, low and sad. Always the reminder of twofoldness: life above, death below.

The local doctor, now in his seventies but still the best and fastest skater around, was skating with me on a winter afternoon that had shifted into twilight. He fell heavily, landing badly on his shoulder, shaken but not deterred. There was one more hour before the light was completely gone, and he wouldn’t leave the lake, not knowing when the ice exhilaration would be his again. His shoulder stiffening, so that later he was almost unable to take his skates off without help, he skated on, on, far into the dusk of the other side of the lake. It wasn’t just the night he was fending off.

Skating is effervescent and evanescent. Vanishing at a point of joy, fleet as the sparrow which St. Bede described, flitting into the dining hall for a brief, warm moment, then out again into the cold and dark, those birds which symbolize the life of the soul.

Of all my friends who skate, the one who knows better than any that life is short and skating days precious is the good doctor who understands that all things rare and lovely must be seized on the instant—that in a lifetime there are so few skating days, and each must be caught with glee.