The fear of war is worse than war itself.

—Seneca, 50Speaking Truth to Power

Jessica Lynch sets the record straight.

I have been asked here today to address “misinformation from the battlefield.” Quite frankly, it is something that I have been doing since I returned from Iraq. However, I want to note for the record, I am not politically motivated in my appearance here today. I lived the war in Iraq. Today I have family and friends still serving in Iraq. My support for our troops is unwavering.

I believe this is not a time for finger pointing. It is time for the truth, the whole truth, versus misinformation and hype.

Because of the misinformation, people try to discount the realities of my story, including me as part of the hype. Nothing could be further from the truth. My experiences have caused a personal struggle of sorts for me. I was given opportunities not extended to my fellow soldiers—and I embraced those opportunities to set the record straight. It is something I have done since 2003, and something I imagine I will have to do for the rest of my life. I have answered criticisms for being paid to tell my story. Quite frankly, the injuries I have will last a lifetime and I had a story to tell, a story that needed to be told so people would know the truth.

I want to take a minute to remind the committee of my true story. I was a soldier.

In July 2001, I enlisted in the Army with my brother. We had different reasons as to why we joined, but we both wanted to serve our country. I loved my time in the Army, and I am grateful for the opportunity to have served this nation during a time of crisis.

In 2003, I received word that my unit had been deployed. I was part of a hundred-mile long convoy going to Baghdad to support the Marines. I drove the five-ton water-buffalo truck. Our unit drove the heaviest vehicles. The sand was thick—our vehicles just sank. It would take us hours to travel the shortest distance. We decided to divide our convoy so the lighter vehicles could reach our target. But then came the city of An Nasiriyah and a day I will never forget.

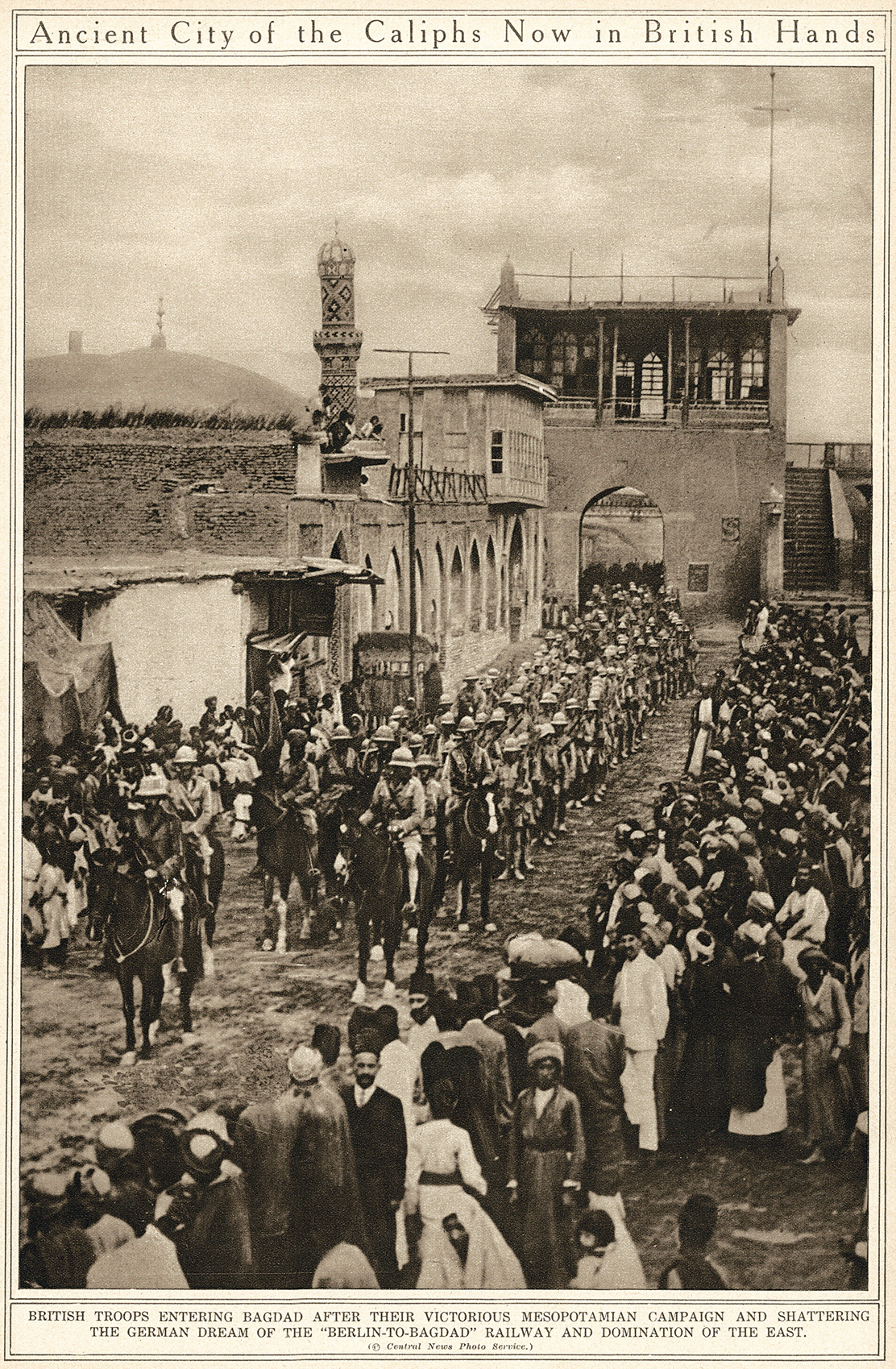

Sir Frederick Stanley Maude leads victorious British troops into Baghdad, 1917.

The truck I was driving broke down. I was picked up by my roommate and best friend, Lori Piestewa, who was driving our First Sergeant, Robert Dowdy. We also picked up two other soldiers from a different unit to get them out of harm’s way.

As we drove through An Nasiriyah, trying to get turned around to try to leave the city, the signs of hostility were increasing with people with weapons on rooftops and the street watching our entire group.

The vehicle I was riding in was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade and slammed into the back of another truck in the convoy. Three people in the vehicle were killed upon impact. Lori and I were taken to a hospital where she later died and I was held for nine days. In all, eleven soldiers died that day, six others from the unit, plus two others were taken prisoner.

Following the ambush, my injuries were extensive. When I awoke in the Iraqi hospital, I was not able to move or feel anything below my waist. I suffered a six-inch gash in my head. My fourth and fifth lumbars were overlapping, causing pressure on my spine. My right humerus bone was broken. My right foot was crushed. My left femur was shattered. The Iraqis in the hospital tried to help me by removing the bone and replacing it with a metal rod. The rod they used was a model from the 1940s for a man and was too long. Following my rescue, the doctors in Landstuhl, Germany, found in a physical exam that I had been sexually assaulted. Today, I continue to deal with bladder, bowel, and kidney problems as a result of my injuries. My left leg still has no feeling from the knee down, and I am required to wear a brace so that I can stand and walk.

When I awoke, I did not know where I was. I could not move or fight or call for help. The nurses at the hospital tried to soothe me and tried unsuccessfully at one point to return me to American troops.

Then on April 1, while various units created diversions around Nasiriyah, a group came to the hospital to rescue me. I could hear them speaking in English, but I was still very afraid. Then a soldier came into my room, he tore the American flag from his uniform and pressed into my hand, and he told me, “We’re American soldiers, and we’re here to take you home.” As I held his hand, I told him, “Yes, I am an American soldier too.”

When I remember those difficult days, I remember the fear, I remember the strength. I remember the hand of a fellow American soldier reassuring me that I was okay now.

At the same time, tales of great heroism were being told. My parent’s home in Wirt County was under siege of the media all repeating the story of the little girl Rambo from the hills who went down fighting.

It was not true.

I have repeatedly said, when asked, that if the stories about me helped inspire our troops and rally a nation, then perhaps there was some good. However, I am still confused as to why they chose to lie and tried to make me a legend when the real heroics of my fellow soldiers that day were, in fact, legendary. People like Lori Piestewa and First Sergeant Dowdy who picked up fellow soldiers in harm’s way, or people like Patrick Miller and Sergeant Donald Walters, who actually fought until the very end.

The bottom line is the American people are capable of determining their own ideals for heroes, and they don’t need to be told elaborate tales.

My hero is my brother Greg who continues to serve this country today. My hero is my friend Lori who died in Iraq but set an example for a generation of Hopi and Native American women and little girls everywhere about the important contributions just one soldier can make in the fight for freedom. My hero is every American who says, “My country needs me,” and answers the call to fight.

I had the good fortune and opportunity to come home, and I told the truth. Many other soldiers, like Pat Tillman, do not have the opportunity.

The truth of war is not always easy to hear, but it is always more heroic than the hype.

About This Text

Testimony before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, April 24, 2007. The dispatches released by the American military and embellished by the American media had decorated PFC Lynch with counterfeit medals for valor.