I am an old scholar, better-looking now than when I was young. That’s what sitting on your ass does to your face.

—Leonard Cohen, 1970Under the Lights

Getting schooled in Texas high school football.

The dominance of football in Texas high schools had become the focus of raging debate all over the state in 1983. The governor of Texas, Mark White, appointed Ross Perot to head a committee on educational reform. In pointing to school systems he thought were skewed in favor of extracurricular activities, Perot took particular aim at Odessa.

On ABC’s Nightline, he called Permian fans “football crazy,” and during the show it was pointed out that a $5.6 million high school football stadium had been built in Odessa in 1982. The stadium included a sunken artificial-surface field eighteen feet below ground level, a two-story press box with VIP seating for school board members and other dignitaries, poured concrete seating for 19,032, and a full-time caretaker who lived in a house on the premises.

“He made it look like we were a bunch of West Texas hicks, fanatics,” said Brad Allen, president of the Permian booster club in the early eighties, of Perot. The stadium “was something the community took a lot of pride in and he went on television and said you’re a bunch of idiots for building it.” Most of the money for the stadium had come from a voter-approved bond issue.

The war against Perot escalated quickly. The booster club geared up a letter-writing campaign to him, state legislators, and the governor. Nearly a thousand letters were sent in protest of Perot’s condemnation of Odessa. Some of the ones to him were addressed “Dear Idiot,” or something worse than that, and they not so gently told him to mind his own damn business and not disturb a way of life that had worked and thrived for years and brought the town a joy it could never have experienced anywhere else.

“It’s our money,” said Allen of the funds that were used to build the stadium. “If we choose to put it into a football program, and the graduates from our high schools are at or above the state level of standards, then screw you, leave us alone.” At one point Perot, believing his motives had been misinterpreted and hoping to convince people that improving education in Texas was not a mortal sin, contemplated coming to Odessa to speak. But he decided against it, to the relief of some who thought he might be physically harmed if he did.

“There are so few other things we can look at with pride,” said Allen. “We don’t have a large university that has thirty or forty thousand students in it. We don’t have the art museum that some communities have and are world-renowned. When somebody talks about West Texas, they talk about football. There is nothing to replace it. It’s an integral part of what made the community strong. You take it away and it’s almost like you strip the identity of the people.”

The pull of it seemed irresistible. Allen’s stepson, Phillip, had been a fullback on the 1980 Permian team that won the state championship. Allen readily admitted that Phillip was not a gifted athlete, but he had the fire and desire that came innately in a town that drank as deeply from the chalice of high school football as Odessa.

Allen knew Phillip was something special in eighth grade, when he had broken his arm during the first defensive series of a game. Rather than come out, he managed to set it in the defensive huddle and played both ways the entire first half. By that time the arm had swelled up considerably, to the point that the forearm pads he wore had to be cut off, and unwillingly he went to the hospital. Allen said he was not proud of the incident, but he told the story freely, for it showed that his son had the ingredients to wear the black and white.

And certainly he wasn’t the only one to have learned the much-admired lesson of no pain, no gain. In seasons past playing for Permian had involved other sacrifices. It had meant the loss of a testicle to a sophomore player when no one bothered to make sure he was thoroughly examined after he had injured his groin several hours earlier during an away game. Subsequently the testicle swelled up to the size of a grapefruit, and by the time the doctor saw him it was too late; it had to be removed. His mother was livid at what had happened, but the player pleaded with her not to push it because he feared it might interfere with his career at Permian and be held against him. He lost the testicle but he did make All-State.

In seasons past, playing for Permian had meant routinely vomiting during the grueling off-season workouts inside the hot and sweaty weight room. It had meant playing with a broken ankle that wasn’t X-rayed because, if it had been known that it was broken, the player would have had to sit out the next game. It had meant playing with broken hands. It had meant a shot of novocaine during halftime to mask the pain of a deep ankle sprain or a hip pointer. It had meant popping painkillers and getting shots of Valium.

Behind the rows of stools stood the members of the 1988 Permian Panther high school football team. Dressed in their black game jerseys, they laughed and teased one another like privileged children of royalty. Directly in front of them, dressed in white jerseys and forming a little protective phalanx, were the Pepettes, a select group of senior girls who made up the school spirit squad. The Pepettes supported all teams but it was the football team they supported most. The number on the white jersey each girl wore corresponded to that of the player she had been assigned for the football season. With that assignment came various time-honored responsibilities.

As part of the tradition, each Pepette brought some type of sweet for her player every week before the game. She didn’t necessarily have to make something from scratch, but there was indirect pressure to because of not-so-private grousing from players who tired quickly of bags of candy and not so discreetly let it be known that they much preferred something fresh-baked. If she had to buy something store-bought, it might as well be beer, and at least one player was able to negotiate such an arrangement with his Pepette during the season.

In addition, each Pepette also had to make a large sign for her player that went in his front yard and stayed there the entire season as a notice to the community that he played football for Permian. Previously the making of these yard signs, which looked like miniature Broadway marquees, had become quite competitive. Some of the Pepettes spent as much as $100 of their own money to make an individual sign, decorating it with twinkling lights and other attention-getting devices. It became a rather serious game of can-you-top-this, and finally a dictum was handed down that all the signs must be made the same way, without any neon.

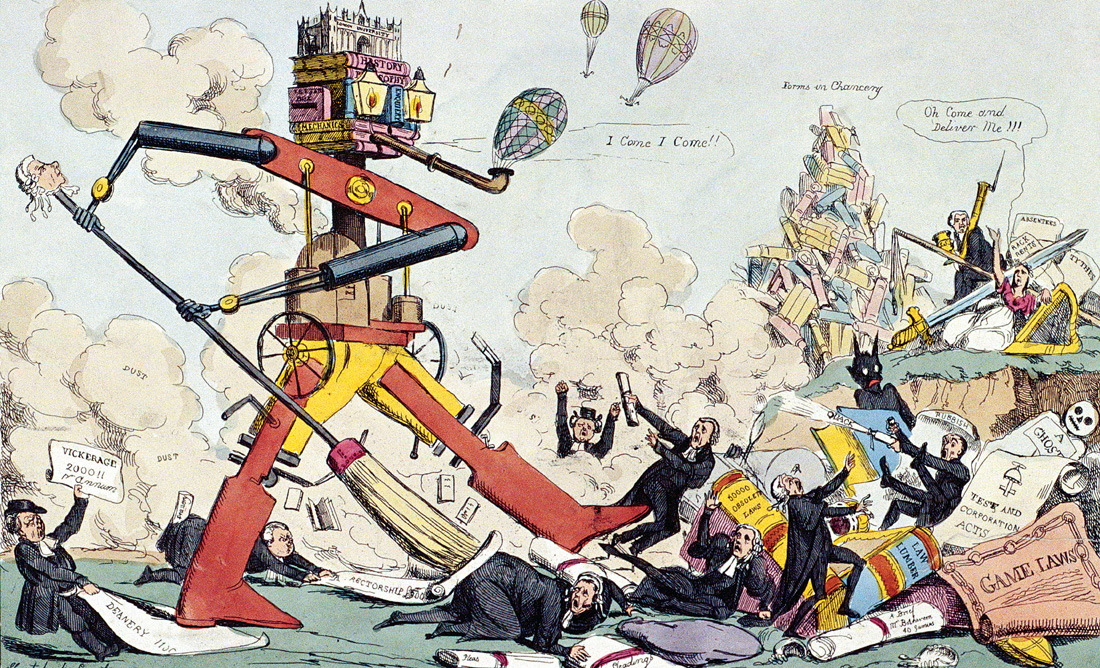

The March of Intellect, a juggernaut figure with London University on its head, sweeping away and kicking lawyers, vicars, and quack doctors, by Robert Seymour, c. 1828. © Guildhall Art Gallery, HIP, Art Resource, NY.

A Pepette also had responsibility for making smaller posters, which went up in the school halls at the beginning of each week and were transferred to the gym for the mandatory Friday morning pep rally. The making of these signs could be quite laborious as well, and one Pepette during the season broke down in tears because she had had to stay up until the wee hours of the morning trying to keep up with the other Pepettes and make a fancy hall sign that her player never even thanked her for.

These were the basic Pepette requirements, but some girls went beyond in their show of spirit. They might embroider the map of Texas on towels and then spell out mojo in the borders. Or they might make mojo pillowcases that the players could take with them during road trips. Or they might place their fresh-baked cookies in tins elaborately decorated in the Permian colors of black and white. In previous years Pepettes had made scrapbooks for their players, including one with the cover made of lacquered wood and modeled on Disney’s The Jungle Book. The book had clippings, cut out in ninety-degree angles as square and true as in an architectural rendering, of every story written about the Permian team that year. It also had beautiful illustrations and captions that tried to capture what it meant to be a Pepette.

“The countryside was filled with loyal and happy subjects serving their chosen panther,” said a caption in a chapter entitled “Joy,” and next to it was a picture of a little girl with flowers in her hand going up to a panther, the Permian mascot, roaring under a tree.

H.G. Bissinger

From Friday Night Lights. Bissinger received a Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting in 1987 for his coverage of court corruption for the Philadelphia Inquirer. His 1998 Vanity Fair article, “Shattered Glass,” tracking the rise and fall of the fraudulent journalist Stephen Glass, became a Hollywood film of the same name.